|

| |

Issue no. 48 - March 1992

pdf

version of this Issue version of this Issue

|

There is much information in this issue that is valuable

and useful. Online readers are reminded, however, that treatment guidelines and health

care practices change over time. If you are in doubt, please refer to

WHO's up-to-date Dehydration Treatment

Plans.

|

updated: 23 April, 2014

Pages 1-8 Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online Issue 48 -

March 1992

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 48 March 1992

Page 1 2

Page 1 2

Best of both worlds

Over 3,000 years ago, practitioners of the Ayurvedic system of traditional medicine in

India were recommending that people with cholera be given quantities of a drink made by

dissolving rock salt and molasses in tepid water. This sounds very like a form of ORT,

developed only this century to prevent and treat dehydration due to diarrhoea. Doubtless

there may be other beneficial treatments in traditional medicine. Despite this, it is wise to be extremely cautious. Traditional remedies can be

dangerous and few have been scientifically tested. Similarly, any integration of healers

into health care services requires careful control and supervision. This issue of DDexplores aspects of traditional healing, a topic that is often raised in letters

from readers.

|

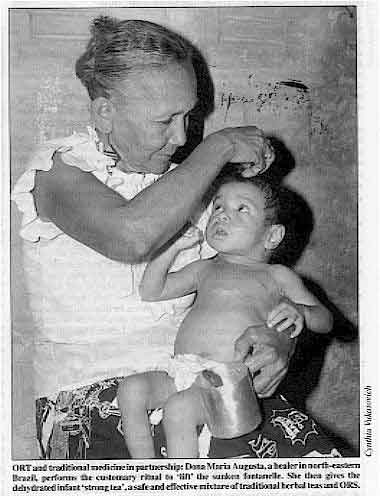

ORT and

traditional medicine in partnership: Dona Maria Augusta, a healer in north-eastern Brazil,

performs the customary ritual to 'lift' the sunken fontanelle. She then gives the

dehydrated infant 'strong tea', a safe and effective mixture of traditional herbal teas

and ORS.

The photo shows a child with diarrhoea being cared for by a traditional healer. The

healer knows that a sunken fontanelle is a sign of dangerous dehydration. She is laying

her hand on the child's head as part of a traditional treatment to 'lift' the fontanelle.

But she is holding in her other hand a cup which contains oral rehydration solution (ORS)

mixed with a herbal tea to give to the child, who is obviously recovering well.

|

|

Ideal way forward?

Conflict and competition between modern and traditional health care systems within

communities can waste valuable resources and hold back vital progress. We are increasingly

realising the complex nature of health needs and the extent to which people use both

modern and traditional systems (see pages="#page2">2,="#page3">3

and 4). Surely the best from both systems ought to be tapped to meet

these needs. The kind of happy compromise illustrated here could be the ideal way forward

for the future in many societies.

|

In this issue:

- Decisions about diarrhoea: understanding people's treatment choices

- Traditional healers - potential for collaboration?

- Update on viral diarrhoeas

- Special supplement on persistent diarrhoea

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 48 March 1992

1 Page 2 3 1 Page 2 3

When do people seek help

. . . and from whom? Understanding the reasons why and when families seek, or do not seek, help for

children with diarrhoea, can help health workers to make education messages and health

services more relevant and effective. Successful community based programmes depend on families knowing how to manage

diarrhoea at home with fluids and food, and recognising when children need treatment by a

health worker. Families often try different approaches - both modern and traditional - to

treating childhood diarrhoea. Choice of approach depends on the type of diarrhoea, what is seen as its cause, and the

availability of health care. When and where families seek help is called 'health seeking

behaviour'. The choices can include:

- home care without drugs;

- home care after asking the advice of a relative or neighbour;

- home medication with purchased drugs or home treatment using traditional remedies;

- visiting a traditional healer;

- seeking advice and/or prescribed treatment from a pharmacist;

- seeking advice and/or prescribed treatment from a health worker in government or private

practice.

To improve health, programmes often try to increase access to modern medical care. But the fact that a clinic or hospital is there does not necessarily mean that people

will use it or accept it. Many will continue to use traditional healers and remedies.

Numerous factors affect when and where families seek help, and why they may not use

modern health services. These include:

- availability e. g. distance from a hospital or health centre, or times

when health workers are on duty;

- affordability e. g. the cost of a consultation or medicines, or the

'cost ' of time required to travel to a health centre;

- acceptability e. g. the level of confidence of a family or community in

a health worker's diagnosis or advice.

Influence of beliefs

Cultural beliefs and attitudes especially affect how a family perceives a child's

illness, the health care and treatment options available to them, and what they decide

about where and when to seek help. Many societies have their own classification systems for illnesses. Diarrhoea, for

example, may not always be described as a single disease. Different types of diarrhoea can

have local names and there may be local beliefs about symptoms, causes and treatments of

the illness. Families may seek treatment for some types of childhood diarrhoea and not for

others, depending on how serious they think the illness is. When a child becomes ill, a family may seek advice from several sources and try a

variety of treatments. The first step is usually home medication, based on local beliefs

about the illness and the advice of family, friends and neighbours. Only later will they

visit a traditional healer, or a pharmacist or physician. People often visit a traditional

healer before taking a sick child to a health centre or hospital.

|

Traditional treatment in Mexico: a woman prepares a herbal tea

for her child, using a local recipe.

Families accept the diagnosis and advice that make the most sense. If there is a big

difference in cultural background and educational status between the community and the

health worker, people may not understand (and therefore not follow) advice, so the

treatment may not seem to 'work'. If advice does not make sense to them or the treatment

does not appear to work, they will usually try another source of health care.

|

|

|

Checklist of questions for health workers Health workers need to find out what local people believe and what action they take

when a child has diarrhoea.

- What are the different names for diarrhoea?

- Do different names mean different types of diarrhoea?

- What do people believe are the causes of these different types of diarrhoea?

- What do people believe about giving food and drinks during diarrhoea? Do they think they

should give:

- extra water or other fluids

- breastmilk

- ordinary foods

- special foods

- Where do people go to seek help?

- What treatments are sold or prescribed by local health providers?

- In the treatment of diarrhoea, what do people believe about the use of:

- local herbs and remedies

- medicines

- pills

- injections

- intravenous drips

- Do people know about ORS? What do they think it is? Do they use it?

|

Dr Patricia Paredes, Instituto de Investigacion Nutritional,

AP18-0191, Lima 18, Peru.

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 48 March 1992

2 Page 3 4 2 Page 3 4

Mexico

A group of mothers in the central highland region of Mexico were asked how they decided

about the severity of diarrhoea and whether their child was getting better or worse. For

them the most important signs were changes in the child's behaviour which interfered with

household activities, such as crying or restlessness. They also took notice of signs

associated with the eyes, and changes in the frequency and appearance of the stools. Most treated diarrhoea with a combination of home remedies and modern medicine. Only 5

per cent said they visited a traditional healer, although herbal teas (made from

more than 12 different herbs), and rice water were commonly given as home remedies. Just

over half of the mothers gave an over-the-counter drug, usually an antibiotic, aspirin, or

a mixture of kaolin and pectin, bought from the local community store or a pharmacy. Only

10 per cent of the mothers used oral rehydration therapy. A third of the mothers took the child to a doctor, either because of vomiting or

persistent diarrhoea. Modern medicine appeals to them because it is used by 'high-status'

people and has scientific authority. Doctors, however, are thought to be cold and aloof,

and people do not always understand what they have to offer. All mothers who went to a

physician continued to use home remedies along with the medicine prescribed. Martinez, H, and Saucedo, G, 1991. Mothers' perceptions about childhood

diarrhoea in rural Mexico. .I. Diar: Dis. Res. 9 no 3:235-243. Thailand

In central Thailand, people use both modern drugs and traditional remedies to treat

childhood diarrhoea. In one study, half of those asked had taken advice from a herbalist.

Modern drugs were widely and inappropriately used for the treatment of diarrhoea, whereas

oral rehydration therapy was only used in about half of cases. Poorer people mostly bought

medicines from local grocery stores. Most people, when asked, did not know anything about the modern medicines they gave

their children, but believed them to be good, particularly those given by injection. Choprapawon, C, et al., 1991. Cultural study of diarrhoeal illness in central

Thailand and its practical implications. J. Diar: Dis. Res. 9 no 3: 204-212. Peru

In a poor area of Lima, the capital city of Peru, we looked at how families chose

treatment for children with diarrhoea. Families sought help outside the home when a child

had signs and symptoms thought to be serious and based on folk beliefs about different

types of diarrhoea. Different treatments were tried as new symptoms appeared during the

course of the illness.

- More than half of the 168 children were given traditional fluids on the first day of

diarrhoea. These included strong teas, herbal teas, and panetela, a weak gruel of

toasted rice, bread and sugar. Over 80 per cent were given such fluids at some point

during the illness.

- Modern drugs were the second most common treatment used. These included

anti-diarrhoeals, antibiotics, or antiemetics - often the remainders of unused

prescriptions from a previous illness in the family. A combination of chloramphenicol and

tetracycline, known as Quemiciclina, used in a single dose, was particularly popular. A

third of these children with diarrhoea were given this drug.

Traditional medicine Traditional medicine is a term used to describe health care that does not fall

within the allopathic 'modern and scientific' health care system. Traditional health care

varies greatly from one country to another and covers a wide range of practices. It includes .systems of medicine with a definite body of knowledge which is written

down and taught formally, for example, traditional Chinese and Tibetan medicine, and

Ayurvedic and Unani systems in India. It also includes 'folk' healers, such as herbalists

and spiritualists, who learn from an older member of the family or special teacher: There are also many traditional 'home' remedies made using recipes that have been

learnt from older relatives.

|

When is outside help sought?

Symptoms which caused the family to seek outside help, from a modern practitioner or a

traditional healer (known as a curioso), included vomiting, listlessness or loss of

appetite. But the duration of diarrhoea was the most important factor - the longer the

diarrhoea continued, the more likely it was that the family took the child to a doctor or

traditional healer.

|

Specific symptoms such as vomiting, persistent diarrhoea or

bloody stools, often prompt families to seek modern medical help, rather than visiting a

traditional healer.

The choice of modern or traditional healer depended on the way in which the family

perceived and described a diarrhoeal illness. Children with blood in the stools or who

passed many stools were more likely to be taken to a modern health facility. Those with

fever were more likely to be taken to a traditional healer.

|

Cases thought to be due to some mystical cause were treated with a traditional healing

method. In contrast, cases described in bio-medical terms (such as infection and

diarrhoea) were more likely to be taken to a modern health facility. Families often used

both systems and were willing to try any and all options to treat their child's illness. Dr Nancy E Levine, Associate Professor of Anthropology, University of California,

Los Angeles, California, USA and Dr Patricia Paredes, Medical Researcher, Instituto de

Investigation Nutritional, Lima, Peru.

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 48 March 1992

3 Page 4 5 3 Page 4 5

| Why families choose traditional remedies |

"We tell mothers to use ORS

and they don't" Carol MacCormack explains why mothers in Jamaica use

traditional remedies for diarrhoea instead of ORS advised by health workers. In Jamaica ORS has been carefully promoted through the health service. Sick children

are seen by a health worker, a packet of ORS is given to the mother, its use explained,

and the mother shown, in the clinic, how to give the solution with a cup and spoon. Health

talks from nurses included the message never to use traditional remedies and only to use

ORS packets. We talked with 263 mothers who had brought children with diarrhoea to

out-patient clinics. Most mothers had heard the ORS message before - on the radio,

television, or from health workers. What mothers do

Diarrhoea symptoms that caused mothers to treat their children included frequent

stools, vomiting, fever and stools which were watery or contained mucus. Very few mothers prepared an ORS solution and gave it to their child. Mostly they gave

traditional remedies. The most common remedies used were coconut water, other fruit juice

or fruit syrup and water, black mint or spearmint tea with sugar, and other sweet 'teas'.

A few gave glucose and water (without salt). When asked what fluids they gave, 3 per cent

of mothers said breastmilk, and 1 per cent, bottlemilk. When asked, 'What does your child like

to drink when he or she has diarrhoea?', most said breastmilk and none said oral

rehydration solution. A second category of traditional remedies was porridges made with

wheat flour, corn meal, arrowroot or banana, flavoured with salt and sweetened with sugar.

A few mothers gave other remedies and over-the-counter drugs, usually laxatives and 'salt

water'. Familiar and less costly

Most of the traditional drinks mentioned are helpful for preventing dehydration. They

were used because they were familiar, easily made or obtained and the child liked them.

Traditional home remedies were also seen to be less costly. It took the best part of a day

to travel to and from a clinic, wait to be seen, and rehydrate the child in the clinic

with a cup and spoon. Mothers went home with only one packet of ORS. The 'cost' of that

packet was a day's time, travel expenses, lost wages, and food for snacks while travelling

and waiting. Mothers could not buy packets of ORS from a nearby pharmacy because they are

not for sale. This meant that, wrongly, some bought laxative salts, done up in little

packets, as a substitute for ORS 'salts'.

|

Home remedies are often preferred to ORS because they are

familiar and more easily available. Both health workers and mothers wanted to do their best for the children. But because

ORS packets were not sold commercially, and health workers warned mothers never to use

traditional remedies, fearing some to be dangerous, children often did not receive either

ORS or sufficient home fluids to prevent dehydration.

|

Carol MacCormack, Bryn Mawr College, Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania 19010, USA. Healers and health services:

working together?

DD reports on recent studies and highlights some key issues. In many cultures, and for a variety of reasons, families often turn first to

traditional healers for advice when a child has diarrhoea. It would seem sensible to try

to ensure that healers give the right advice about fluids and feeding, and that harmful

practices are discouraged.

|

Many healers receive training in traditional medicine, from,

for example, a recognised association. However, they may need additional training in

treating diarrhoea with ORT. The potential for collaboration between the traditional and modern medical systems is

being explored in some countries. Researchers have looked at how traditional healers treat

diarrhoea and dehydration, and have tried to assess the extent to which it is possible to

incorporate ORT into their practices.

|

|

Zambia: advantages and disadvantages

Recognising the important role of traditional healers, the Ministry of Health in Zambia

created a Department of Traditional Medicine, and supported the setting up of a

traditional practitioners' association. A survey by the national CDD programme identified

three groups: herbalists, spiritualists and faith healers. Most were aware of the commonly recognised causes of diarrhoea, including bad food,

poor hygiene and contaminated water. The usual treatment consisted of drinks of roots or

herbs mixed with water; in some cases, porridge was recommended. Most healers could

recognise the signs of dehydration and 79 per cent said they would be willing to advise

giving oral rehydration therapy. The majority of traditional healers were keen to learn about ORS, but an intensive

training effort would be required to overcome problems such as overdosing with toxic

herbal mixtures, and advising mothers to stop breastfeeding. Dr Paul J Freund, PRITECH, PO Box 37580, Lusaka, Zambia. Continued on next page

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 48 March 1992

4 Page 5 6 4 Page 5 6

| Traditional healers and remedies |

Brazil: the ORT 'ritual' In north-eastern Brazil, diarrhoea is a serious child health problem. Families consult

a wide variety of traditional practitioners, as well as village health workers, nurses and

physicians. The variety of healers and therapies often results in mixed messages,

incomplete care and the child's eventual death. But 'modern' medicine is not always an

option, due to problems in health care delivery, and people continue to turn to the

traditional sector. In one study, it was found that 83 per cent of rural mothers first seek help from

traditional healers if their children have diarrhoea. Almost all urban mothers taking

their children to a rehydration centre for intravenous rehydration had already consulted a

healer. Diarrhoea is perceived by many parents as a variety of folk maladies - evil eye,

fright disease, spirit intrusion, intestinal heat, or sunken fontanelle - and traditional

healers are believed to have the spiritual power to cure a sick child. Realising that many families seek help from traditional healers, the primary health

care programme (PROAIS) at the Federal University of Ceara worked with them to deliver

ORT. Together, healers and researchers developed an ORS-tea which combines traditional

herbal anti-diarrhoeal teas with the correct mixture of salt and sugar, using a simple

bottle-cap measure. Teaching materials on the prevention and treatment of diarrhoeal

diseases were developed based on local beliefs about childhood illness, to be easily

understood by non-literate mothers. Healers integrate ORT into their customary rituals for

treating evil eye or a sunken fontanelle (as shown in the="#page1">picture on page

1). Intensive training of 400 traditional healers was shown to increase the number of

mothers using ORT, alter a number of dangerous health care practices, and reinforce

preventive behaviours to stop diarrhoeal disease transmission. Infant mortality was

significantly reduced, compared with control communities where healers were not

mobilised.

Introducing ORT in this way worked because it did not try to alter popular medical customs

and beliefs, but built on them instead. Dr Marilyn K Nations, Rua dos Tabajaras 575/700, Fortaleza, Ceara, Brazil. Cameroon: interest in oral rehydration therapy Fifty traditional healers in the Cameroon were asked how they treat diarrhoeal

diseases. The healers were either herbalists, priests or diviners. Five different

organisations of traditional healers were active in the four regions visited, and most

were registered with the government. But not all healers belong to an association and they

do not have to be registered to practise. Those interviewed divided diarrhoeal diseases into two groups: those where a specific

cause cannot be determined, and those with a specific cause. Treatments included harmful

practices (65 per cent said they gave purging remedies) and beneficial ones (26 per cent

began by giving something to drink).

|

Research is needed to find out whether traditional remedies are

safe, and effective for treating diarrhoea. Only a few had heard of or used oral rehydration therapy, and none knew how to make an

oral rehydration solution correctly or gave it in large enough quantities to be effective.

But, when the purpose of ORT was explained, the healers expressed great interest in using

it. Most had a favourable view of the role of modern medicine, except where the cause of

illness was believed to be "super-natural'. Patients were often treated

simultaneously by traditional and modern healers, and it is not unusual for healers to

send a remedy to a patient in hospital. Physicians also seemed impressed by the conviction

of health workers and patients that traditional medicine is effective.

|

Referrals took place between hospitals and healers, and between one healer and another.

The main issue, which is not easy to address, is that of how to organise collaboration. Flavien Ndonko, PRITECH/USAID, Rue Nachtigal, BP 817, Yaoundé, Cameroon. Uganda: first source of health care Nearly 300 traditional healers in Uganda were asked how they treated diarrhoea and what

they believed to be the causes. The healers saw many cases of diarrhoea, and their beliefs

about the causes mostly coincided with modern medicine - including poor sanitation,

unclean water, and eating contaminated foods. They used a great variety of herbs and plants, given with varying amounts of water, to

treat diarrhoea. Twenty five per cent considered extra fluids to be necessary, and almost

three quarters advised patients to take as much fluid as possible, including water, milk,

fruit juices, porridge, tea, sugar and salt solutions. A few. however, advised restricted

fluid and food intake. Many healers recognised their limitations and, if the diarrhoea had

not subsided after 1 to 3 days, advised patients to seek treatment at a hospital. These traditional healers provide the first source of health advice and treatment to

most people in rural areas. Since they live with the people and share their customs and

traditions they might have the potential to increase use of oral rehydration therapy,

given careful training to improve their existing techniques. Anokbonggo W et al., 1990. Traditional methods in management of diarrhoeal diseases

in Uganda. WHO Bull. vol68, no 3: 359-363. Continued on next page

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 48 March 1992

5 Page 6 7 5 Page 6 7

| Traditional healers and remedies |

Issues to consider Some of the advantages and disadvantages of involving traditional healers in the

promotion of oral rehydration therapy are: Advantages

- Traditional healers are often the first providers of health care for many families in

both rural and urban areas.

- Traditional healers are present in far greater numbers than modern medical personnel in

many countries.

- Traditional healers are already treating many cases of diarrhoea.

- The cost of providing ORS and training for traditional healers might be lower than

training costs for medical staff.

- Traditional healers work in the community and are familiar with what people think about

illness and the attitudes of mothers. Promotion of ORT may be more readily accepted from

traditional healers.

Disadvantages

- Traditional healers are not always organised and may be hard to reach with training

programmes; targeting and selecting healers may be difficult and not all are motivated to

collaborate.

- There is still mistrust of traditional medicine by the medical establishment and of

doctors by healers.

- The problem of overdosing and use of potentially dangerous and toxic substances in young

children in particular is a serious issue.

- There are harmful practices, such as purging (which need to be discouraged).

- If traditional healers do not treat diarrhoea correctly, children may develop more

serious dehydration and be taken too late to clinics.

- There may be inappropriate adaptation of treatments - for example not giving enough

fluid to combat dehydration.

|

Problems with purging practices Use of enemas and purgatives has been recorded in many parts of the world, but the

extent is not well documented. Jemima Hayfron-Benjamin writes

from Ghana and warns of the dangers. Taking an enema is common in Ghana. Elderly people, pregnant women, children and the

sick are given enemas regularly, especially in rural areas where there are inadequate

health services, and in urban slums. It is a traditional technique, culturally accepted

and popular, and is often the first treatment at home for fever, cough, constipation,

flatulence, diarrhoea and pain. Enemas are used in medicine to clean the bowel before surgery or during labour, and to

stimulate bowel motility after surgery. The practice of giving enemas and purging with

strong herbs and other substances can be very harmful, especially in young children. If

the active ingredients are toxic or corrosive, these can damage the intestines, leading to

ulceration, perforation, peritonitis, septicaemia and even death. I have seen many children who have collapsed after being given enemas containing a

range of concoctions from cassava and ginger to remedies from traditional healers. For example, an 8 year old girl presented with acute abdominal pain. The mother said

her daughter had been feeling ill for a few weeks, with abdominal pains, loss of appetite,

vomiting, severe weight loss and diarrhoea, so the mother gave her enemas from time to

time. After the last enema. she noticed her daughter's condition was deteriorating and

rushed her to hospital. The girl was pale looking, dehydrated and emaciated, feeling

thirsty, vomiting occasionally and feverish. We diagnosed typhoid fever with a perforated bowel following an enema, peritonitis and

septicaemia. Because of the seriousness of the condition, she was rushed to theatre for an

emergency laparotomy. Fortunately the child survived. In another instance, a 9 month old baby girl was brought to us unconscious, with

rolling eyeballs, signs of pulmonary oedema, early cardiac failure, severe anaemia and

twitching. The child had diarrhoea two days before and was given an enema that morning.

Afterwards the child collapsed and was rushed to hospital where she died an hour later

from acute cardiac failure and cerebral oedema caused by poisoning from the enema. Unanswered questions Giving enemas to children is widely practised, but we do not know enough about the

problems this may cause. Unanswered questions include:

- When and why do families give enemas to their children?

- Are they aware that enemas may be dangerous?

- Which substances are used for purging and which of these are toxic, and in what

concentrations?

- To what extent do enemas contribute to mortality in small children?

- How can this traditional practice be made safer or discouraged?

'Modern' enemas: toxic chemicals In South Africa some traditional healers were found to have caused harm to patients by

'modernising' their use of purgative enemas. Whereas enemas traditionally consisted of

plant extracts, given through a truncated cow horn or hollow reeds, these have been

replaced by domestic and industrial chemicals given with syringes or through rubber

tubing. Some of these chemicals are toxic, and can cause severe damage to the bowel. Dunn, J P et al., 1991. Colonic complications after toxic tribal enemas. Br.

J. Surg. 78: 545-48.

|

Dr Jemima Hayfron-Benjamin, Central Hospital, PO Box 174, Cape Coast,

Ghana. DD would be interested to hear from readers about this subject.

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 48 March 1992

6 Page 7 8 6 Page 7 8

Developments in diagnosis and vaccines

Viral infections account for over a quarter of severe childhood diarrhoeal

episodes in developing countries. Ruth Bishop discusses the

importance of different viruses and reports on recent progress in rotavirus vaccine

development. Viruses are an important cause of diarrhoea in young children. More than 50 per cent of

diarrhoea in children admitted to hospital in industrialised countries is associated with

viruses infecting the intestinal tract. Bacterial enteric infections are more common in

children in developing countries, so the proportion of severe diarrhoea due to viruses is

less, approximately 25 to 30 per cent, but is still important. Rotaviruses Rotaviruses are the single most important infectious cause of severe acute diarrhoea in

young children throughout the world. The CDD programme at WHO considers development of a

vaccine to prevent rotavirus infection to be a priority. Field trials of vaccines have been held in Europe, USA, South America, Africa and Asia.

The trials have used animal rotaviruses (from calves or young monkeys) that are very

similar to human rotaviruses.

|

Rotavirus particles in diarrhoeal faeces, as seen using an

electron microscope.

These animal rotaviruses are grown in cell culture and are given orally as live

viruses. They seem to grow in the human intestine and produce serum antibodies without

causing disease. The monkey rotaviruses have occasionally caused mild fever, but are

considered safe for children.

|

Initially the effects of the vaccines were studied mainly in children aged 6 to 18

months. But the importance of early vaccination has now been realised, and most vaccine

trials now involve infants aged 3 to 4 months. In breastfed infants there may be some

interference with vaccine 'take' from high levels of maternal antibody in breastmilk, but

this might be overcome by giving more than one dose of the vaccine, perhaps at monthly

intervals. In trials to date, the vaccines have performed best in children in Europe and

the USA, where efficacy rates up to 70 to 80 per cent have been seen. There are four main rotavirus serotypes. To be effective, a vaccine must be able to

protect against disease caused by each serotype. One approach is to develop a combined

vaccine that contains all four serotypes. These combined vaccines have been shown to be

safe, and a major trial of the effectiveness of one mixture will start soon in Venezuela. The rotavirus vaccines tested so far are not suitable for release by their

manufacturers because of their limited efficacy. If the trial in Venezuela is successful,

it is possible that this vaccine could be made available for more widespread use by 1994.

It is hoped that a rotavirus vaccine could be combined with oral polio vaccine, without

decreasing the 'take' of either vaccine. There is preliminary evidence that the oral

rotavirus vaccines tested so far do not interfere with the effectiveness of oral polio

virus vaccine when given in combination. If this proves to be correct, then it is probable

that oral rotavirus vaccines could be incorporated in the EPI schedule. Researchers are also trying other approaches to the production of rotavirus vaccine.

These include attenuated human virus, and production of genetically engineered vaccines.

All strategies have focused on development of oral vaccines as it is thought that

parenteral vaccines are less likely to be effective. Enteric adenoviruses Adenoviruses of serotypes 40 and 41 have been shown to cause severe acute diarrhoea in

6 to 8 per cent of young children admitted to hospital in developed countries. The

diarrhoea is generally of longer duration than that caused by rotaviruses. Enteric

adenoviruses also cause severe diarrhoea in young children in developing countries, but

their importance seems to vary from country to country, and further studies are needed to

see whether they are involved in chronic illness and development of malnutrition.

|

Adenovirus particles in diarrhoeal faeces. Diagnosis by

electron microscopy is no longer necessary, as special chemical tests have been developed.

Diagnosis of infection by electron microscopy is no longer necessary; sensitive and

specific ELISA assays are now available.

|

|

'Small' viruses These include astroviruses, caliciviruses, Norwalk viruses and others. It seems likely

that infection due to a number of different small viruses could explain many diarrhoea

episodes from which no pathogen is isolated. Several 'small' viruses have been shown to

cause epidemics of food-borne or water-borne diarrhoea and may prove to be important in

developing countries. Recently some laboratories have developed specific ELISA assays for

these viruses, and it may soon become possible for laboratories in developing countries to

find out how important these viruses are as a cause of severe disease in young children. Professor Ruth Bishop, Department of Gastroenterology, Royal Children's Hospital,

Parkville, Melbourne, Victoria 3052, Australia. Barnes, G L, 1991. Intestinal viral infections. in: Paediatric Gastrointestinal

Disease, ed Walker WA et al., B C Decker lnc, Philadelphia, pp538-546. Cook, S M et al., 1990. Global seasonality of rotavirus infections. Bull WHO 68:

171-177. Madeley; C R. 1986. The emerging role of adenoviruses as inducers of

gastroenteritis. Paed. Infect. Dis. 5: 563-574.

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 48 March 1992

7 Page 8 7 Page 8

Deworming for older children? Following William Cutting's comment in DD47, Andrew

Tomkins discusses some benefits of deworming programmes.

Dr Cutting raises important issues about appropriate strategies against

helminths.

While it is true that pre-school children suffer a considerable burden of ill health, I am

concerned that the current emphasis on child survival programmes has led to the neglect of

the health of school-age children. The impact of helminths on growth and development of

school-age children needs to be seriously considered. While it is important to emphasise the need to improve water supplies and sanitation,

after a decade of highlighting these issues many children still live in disadvantaged

environments. Is it, therefore, reasonable to rely on environmental control and improved

personal hygiene alone to reduce the prevalence of gut parasites? Many parents would argue

that it is not, and in many countries purchase of anti-helminthic drugs, even by poorer

families, is seen as a high priority. Drug costs have fallen quite markedly over the last few years. In a programme in

Indonesia, over 80 per cent of parents with children attending schools pay US$0.50 per

year for a service which, among other aspects of health care, involves distribution of

anti-helminthic drugs. In Zanzibar, the Department of Education has decided to distribute

them through schools. Environmental improvements and oral rehydration are crucial, and should be emphasised

at all times. They are not sufficient, however. Programmes which emphasise the importance

of personal hygiene, sanitation and safe water supply can act in tandem with

deworming. These approaches are not just part of another vertical programme to be imposed on a

community. Parents are looking to schools as an investment in the future of their

children. They may well regard initiatives in parasite control as something to be

welcomed. Professor Andrew Tomkins, Institute of Child Health, 30 Guilford Street, London WC1N

1EH, UK.

Traditional handwashing The Shona community in Zimbabwe customarily teaches children to wash their hands before

meals. People used to pour water over their hands from a locally made earthenware vessel

with a long, narrow spout. Families now tend to wash their hands communally, using a

wide, flat dish, with the youngest children washing their hands last. I wanted to find out if this way of handwashing involves a greater risk of infection

than the traditional method, and if teaching people to wash their hands under running

water would affect the incidence of diarrhoea. I selected the mothers of 70 children who

came to the local hospital with severe diarrhoea. Half were taught about washing hands

under a running tap or in water poured over them from a vessel. The other half were not

taught this method. After nine months, fewer than half the children of mothers in the first group had come

to the hospital again with diarrhoea infections, whilst nearly three quarters of the

children in the 'control' group had been brought to the hospital. Although very small, the

study encouraged us about the health benefits of educating people about washing their

hands under running water. Dr Vitalis Chipfakacha, Senior Regional Medical Officer, PO Box 5,

Tsabong,

Botswana.

Note: In this community there was no shortage of running water.

'Keep animals out of your house!' The health team of WaterAid is trying to help people in rural and semi-urban

communities of Nepal to build and use hygienic toilets. After reading DD45 we will also try to prevent the spread

of disease by animals, especially chickens.

|

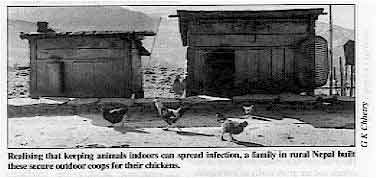

Realising that keeping animals indoors can spread infection, a

family in rural Nepal built these secure outdoor coops for their chickens. |

Chickens are kept for economic and religious reasons. In poorer communities, ' people

keep them inside their houses. We now intend to try to encourage people to build chicken

coops and to keep chickens out of the house. G K Chhetry, Health Co-ordinator, WaterAid, Nepal.

|

Scientific editors Dr Katherine Elliott and Dr William Cutting

Managing editor Kathy Attawell

Assistant editor Nel Druce

Editorial advisory group

Professor J Assi Adou (Ivory Coast)

Professor A G Billoo (Pakistan)

Professor David Candy (UK)

Professor Richard Feachem (UK)

Dr Shanti Ghosh (India)

Dr Michael Gracey (Australia)

Dr Nicole Guérin (France)

Dr Norbert Hirschhorn (USA)

Dr Sharon Huttly (UK)

Dr Claudio Lanata (Peru)

Professor Leonardo Mata (Costa Rica)

Dr Jon Rohde (USA)

Dr Mike Rowland (UK)

Ms E O Sullesta (Philippines)

Professor Andrew Tomkins (UK) With support from AID (USA), ODA (UK), UNICEF, WHO Publishing partners

BRAC (Bangladesh)

CMAI (India)

CMU (China)

Grupo CID (USA)

HLMC (Nepal)

lmajics (Pakistan)

ORANA (Senegal)

RUHSA (India)

Consultants at University Eduardo Mondlane (Mozambique)

|

Issue no. 48 March 1992

Page Navigation

This edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online is produced by Rehydration Project. Dialogue on Diarrhoea was published four times a year in English, Chinese, French, Portuguese, Spanish, Tamil,

English/Urdu and Vietnamese and reached more than a quarter of a million readers worldwide. The English edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea was produced and distributed by Healthlink Worldwide. Healthlink Worldwide is committed to strengthening primary health care and

community-based rehabilitation in the South by maximising the use and impact

of information, providing training and resources, and actively supporting

the capacity building of partner organisations. - ISSN 0950-0235 Reproducing articles

Healthlink Worldwide encourages the reproduction of

articles in this newsletter for non-profit making and educational uses. Please

clearly credit Healthlink Worldwide as the source and, if possible, send us a copy of any uses made of the material.

|

updated: 23 April, 2014

updated: 23 April, 2014

|