|

| |

Issue no. 57 - July-August 1994

pdf

version of this Issue version of this Issue

|

There is much information in this issue that is valuable

and useful. Online readers are reminded, however, that treatment guidelines and health

care practices change over time. If you are in doubt, please refer to

WHO's up-to-date Dehydration Treatment

Plans.

|

Pages 1-8 Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online Issue 57 -

June-August 1994

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 57 June-August

1994  Page 1 2

Page 1 2

Sanitation solutions

|

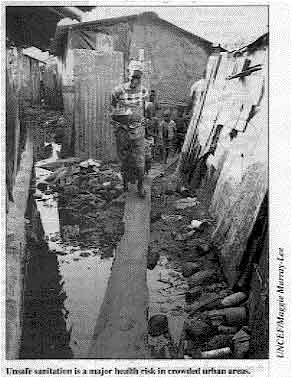

Unsafe sanitation is a major health risk in crowded urban areas. Most of us do not need to be told that

human faeces are a health risk if not disposed of safely. Germs in faeces can be passed to

people's hands, food, or water, then swallowed, spreading disease.

Safe disposal of faeces is a priority for preventing diarrhoea. A recent review of

studies showed that sanitation had a greater impact on improving child health than water

provision, yet health programmes have often concentrated on safe water rather than

sanitation.

|

|

This issue of DD looks at what can be done to improve sanitation in a range

of settings - including urban areas, poor rural communities and refugee settlements.

We describe sanitation systems that are low-cost and can be adapted for different cultures

and environments. In providing this information, DD is not recommending any

one technology above another. Different systems will suit different settings - people's

needs and resources must be the starting point. Sanitation is not just about building latrines. Changing people's behaviour is crucial.

Even when latrines are available, people must be motivated to use and maintain them, and

to practise good hygiene such as hand-washing. If families cannot afford latrines, much

can still be done to ensure faeces are disposed of safely. Changing sanitation behaviour is very challenging because defecation is a sensitive and

private subject. Few of us would be happy discussing our most intimate toilet habits with

strangers! However, there are ways of tackling the subject sensitively. An article on="#page3">page 3 describes how participatory techniques can tap communities'

existing experience of solving sanitation problems and involve people in planning

sanitation that suits their needs. Another approach is to influence children's behaviour. Most hygiene behaviours are

learnt at a young age. Children who are taught to use a latrine and wash their hands when

they are very young will naturally pass messages about this behaviour to their own

children when they grow up. In addition, it is often less embarrassing for mothers to

discuss children's hygiene practices and how to improve them, rather than directly

describing their own habits.

| DD would like to hear from readers about ways they

have worked with communities to improve sanitation, and what has (and has not) been

successful. |

|

In this issue:

- Pit latrines with a difference Page 4

- Emergency sanitation measures Page 5

- Communicating better hygiene Page 8

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 57 June-August

1994  1 Page 2 3 1 Page 2 3

Sanitation - an unmet challenge Mayling Simpson-Hébert argues for sanitation to be

given priority in health planning. More than a third of the world's

population does not have access to latrines or toilets for safe disposal of

faeces. Even

if governments and other agencies continue to build sanitation facilities at the current

rate, population growth means that the number of people (around 2 billion) without

sanitation facilities by the year 2025 will stay the same. Poor sanitation is a particular problem in crowded urban environments where lack of

space makes unsafe disposal of faeces especially dangerous. As developing countries become

more urbanised, improving sanitation for millions of low-income city dwellers must be a

priority. Inadequate sanitation is a major cause of diarrhoea which kills 2.5 million young

children every year, and of intestinal helminths (worms) which cause poor growth and

development in children. Good sanitation is not just about building latrines. In communities without resources

to build latrines, safer sanitation may involve setting aside restricted areas for

defecation and burying faeces. Also much disease can be prevented through better hygienic

practices associated with sanitation (such as hand-washing) even if latrines are not

available. Yet despite evidence that sanitation is extremely important to health, it lags behind

the provision of water supply. Why is this? The topic of sanitation is uncomfortable. Health workers have not yet been able to

break through cultural barriers to discussing sanitation. Households and communities have been offered few choices, and when options have been

provided these are usually expensive. Sanitation has been equated with latrines, rather

than with gradual improvements in safe excreta disposal according to what communities can

afford. More research is needed to provide users with greater choice in sanitation technology.

Systems must be adaptable so that households can upgrade them when their finances allow,

and technologies should take account of cultural and geographical differences. Promotion of sanitation has been weak. We used to believe that if we told people about

sanitation and showed them the technology then they would adopt it. Little work has been

done to create demand - to 'sell' the idea that sanitation is a desirable asset - or to

involve communities in decision making so that sanitation meets their needs and

preferences. If communities recognise the need for each household to contribute to

reducing disease, social approval is likely to encourage more households to invest in

sanitation facilities.

SANITATION

refers to the safe disposal of human faeces.

|

Given difficult economic times and continued rapid population growth, we

need to set priorities. Even if we greatly increase sanitation provision, it is unlikely

that facilities can be provided to everyone who needs them in the next 25 years. Since much excreta-borne disease can be prevented by hygiene practices such as

hand-washing and better food handling, 'hygiene promotion for all; full latrine coverage

for high-risk populations* ' may be more realistic goals. Hygiene education requires understanding community beliefs, values and practices, and

training extension workers in communication skills and innovative educational methods

which can be adapted to suit particular cultures. Educational efforts should focus on

children since behaviour change often takes a whole generation. Women all over the world have the main responsibility for home economics, sanitation

and personal hygiene of children. A special effort should be made to involve women in

designing, promoting and making decisions about sanitation. Dr Mayling Simpson-Hebert, Community Water Supply and Sanitation Unit, Division of

Environmental Health, WHO, CH-1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland. Adapted from an article in Environmental Health. No. 20, October 1993.

* Key high risk populations are communities that use surface water

for drinking, those in crowded urban areas without facilities for safe disposal of

excreta, and communities where excreta-related disease is common.

|

Interrupting transmission

|

The 'F' diagram above summarises the main ways diarrhoea is spread -by faecal

germs contaminating fields, fluids, fingers, flies or food, then eventually being

swallowed. Most latrines will stop the 'fluids' and 'fields' transmission routes. Some of the more

sophisticated latrines such as the ventilated improved pit (VIP) latrine and the

pour-flush latrine may also break the 'flies' route.

However, no type of latrine can prevent contamination of hands and fingers. Good

hygiene behaviour is needed for this, especially thorough washing of hands after

defecation or contact with faeces.

Uno Winblad, Pataholm 5503,384 92 ALEM, Sweden.

|

|

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 57 June-August

1994  2 Page 3 4 2 Page 3 4

Learning from people Sarah Bradley explains how participatory techniques can

tap local knowledge of solving hygiene problems.

|

It is particularly important that women are involved in making

decisions about sanitation.

'It is not often that I go to a workshop like

this. We played games. We slept in tents. The community taught us instead of the other way

around. After the initial shock we learnt a lot, and it was fun! '

|

This was the reaction of an environmental health officer to a UNICEF workshop in a

mountain town in Tigray in the horn of Africa. The workshop provided training for

environmental health officers in facilitating communities to improve sanitation and

hygiene practices. Participatory techniques were used to change attitudes to learning, and

games highlighted key points. Participants learnt the importance of using several information-gathering methods so

that information can be checked against other sources. The most important techniques are

listening and observing. The community was asked to provide information by drawing pictures, maps, charts and

diagrams. Once community members realised their knowledge was valued, communication was

easy. A group of women drew diagrams showing how far water sources were from the town. By

drawing pictures, the women showed how they prioritised water use, re-using washing water

for watering plants, and collecting drinking water from cleaner sources while setting

aside more polluted sources of water as animal drinking places. Even though water was

scarce, most people washed their hands before eating food. The environmental health

officers were amazed: 'We had no idea these people knew so much or could it express it so

well. ' It was clear that hygiene knowledge was widespread even though it was not always put

into practice. Inadequate sanitation was due to lack of information about technology

choices. Traditionally, latrine platforms had been made of wood, but deforestation meant

wood was expensive. Once the problems were clear, solutions could be found. In this remote mountain area

the technique of arching - using stones to build domes - was not known. Our sanitation

adviser worked with local masons to promote the building of stone domes over round pits to

support small concrete 'sanplats' (see below). During

the workshop, nine pits were dug by householders and many more were started. The masons

be- came experts in building stone domes. Community members copied their maps onto cloth

to hang in the public health office and clinic. As new latrines are made they will be

marked on the maps. The environmental health officers went back to their own communities determined to find

out about local knowledge there. They saw for themselves that participatory techniques not

only promote discussion, but also mobilise the community to action. giving people

confidence in their ability to change their situation. Sarah Murray Bradley, 89 Keslake Road, London NW6 6DH, UK.

|

The Sanplat

system Sanplats are small concrete squatting slabs which can be put on top of traditional

latrines to make them more hygienic. A sanplat has:

- smooth and sloping surfaces for easy cleaning

- raised foot-rests to enable users to find the right place to squat even in the dark

- a keyhole-shaped drop-hole making it safe even for very small children to use

- a tight-fitting lid to stop smells and keep out flies.

Sanplats are made in three sizes:

- small square (60cm2),

- medium round (1.2m diameter), and

- large round (1.5m diameter).

The small one is used in rural areas to improve traditional latrines and is suitable

for use on top of a stone dome as described in the article to the left.

A 50kg bag of cement can make 5-6 small sanplats. Small sanplats can easily be carried

to distant communities.

The two round sanplats are dome-shaped and go directly on top of a round pit, with or

without a lining depending on the soil conditions.

|

|

Stone domes can support sanplats

For more information write to:

Björn Brandberg, LCS, Flo 18, Levenskog, S-467-96, Grästorp, Sweden.

|

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 57 June-August

1994  3 Page 4 5 3 Page 4 5

Simpler, cheaper VIP latrines Peter Morgan, one of the designers of the ventilated

improved pit latrine, looks at ways of making pit latrines less expensive for rural

communities. In the last fifteen years, ventilated

improved pit (VIP) latrines have been promoted as one of the main options for rural

sanitation in many parts of Africa. VIPs consist of a lined pit, a concrete slab with a squat hole covering the pit. a

roofed shelter and a ventilation pipe covered with a fly screen. They have proved to be very popular with users because the vent pipe minimises bad

smells and flies. However, for communities with limited resources and skills, VlPs are

still too expensive and complicated to build. A standard VIP latrine in Zimbabwe (known as a Blair latrine) uses fired bricks

cemented together for the pit lining, the shelter, and often for the vent pipe.

Alternatively, vent pipes are made of PVC (hard-wearing plastic) or asbestos. Each VIP requires between three and five 50kg bags of cement (depending on the model

used) and costs on average US$ 60, including labour. Although they last for more than 10

years, they are beyond the means of most rural communities unless they have outside

funding. Very low-cost versions Recently, Zimbabwe's Mvuramanzi Trust has been experimenting with very low-cost

adaptations of the VIP. The simplest have lightweight shelters made of reeds or grass, or

poles and mud. If the shelter is light-weight and the ground firm, a fully lined brick pit

may not be required. A partial lining with bricks built up on a ledge cut in from the pit

wall, half a metre from the top, may be sufficient. Alternatively, a 'ring beam' of large

stones around the top of the pit reinforced with cement may be adequate. A concrete slab with a squatting hole and vent hole is needed to cover the pit. Al

together, only one bag of cement is used. A low-cost vent pipe can be made with local

materials. The simplest are made of reeds wired together to form a tube. This then needs

to be covered to make it airtight and water-resistant. Cement mortar can be used for this

or alternatively plastic from discarded bags can be neatly wrapped around the reed tube

and bound with twine. A further layer of grass over the plastic protects it from

disintegrating in the sun. In Tanzania, a tube-shaped bag made of coarse cloth is used as a mould and is plastered

with a mixture of sand and cement to form a pipe. In Zimbabwe, an excellent low-cost vent

pipe is made by plastering a mould made of bundles of grass with a mixture of 3 parts of

sand to 1 part of cement. The grass is removed once the pipe has dried. Four pipes, 2.4m

long and 11Omm in diameter, can be made from a bag of cement. All vent pipes should be covered with a corrosion-resistant fly screen. Aluminium

screen works well and is cheap, although in most African countries it is imported. More durable alternatives Where bricks are available, they can ensure that the latrine lasts for a long time. In

very low-cost versions, bricks used for the shelter do not need to be fired. Instead they

can be dried in the sun. In Zimbabwe, traditional houses built with bricks made from

termite soil are very durable if protected with an overhanging thatched roof. Ideally,

fired bricks should be used for the vent pipe. However, the cement tube described earlier

is suited to a sun-dried brick structure fitted with a grass roof. Whether bricks used in the structure are fired or not, for safety reasons the pit must

be lined with tired bricks and cement mortar. Even so, it is still possible to build a

durable VIP with fired brick lining using only two bags of cement. While low cost VIPs require more maintenance than standard, more expensive models, and

do not withstand extremes of weather so well, they rely on traditional materials and

skills rather than on imported materials and are therefore more easily built by rural

communities. Peter Morgan, Mvuramauzi Trust, Box A547, Avondale, Harare,

Zimbabwe. The Mvuramanzi Trust has produced a series of manuals on how to build

low-cost VIP latrines. For copies, write to the address above.

|

Stages in construction of a low-cost VIP

|

1. Adding a concrete slab to the top of a brick-lined pit

2. Making a lightweight structure

3. Adding a roof of grass

4. Completed VIP with a locally-made vent pipe

|

|

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 57 June-August

1994  4 Page 5 6 4 Page 5 6

Emergency measures Safe disposal of faeces is essential in emergency settlements as Joy

Morgan of Oxfam explains. Good sanitation is especially important in areas

of high population density. When there is a gradual movement of populations from rural to

urban areas, communities can slowly adapt their hygiene behaviour to cope with the change.

How ever, in emergencies thousands of displaced people gather almost overnight, making

safe disposal of faeces an urgent priority. The key issues for sanitation in emergencies are restricting excreta disposal to

certain areas and finding sanitation solutions that are acceptable to the people involved. It is also important to be sensitive to the fact that people living near an emergency

settlement may not have adequate sanitation. Where possible, local communities should be

included in sanitation programmes developed for displaced populations. Also, the design

for emergency sanitation facilities should respect government policy. For example, in

refugee camps in Uganda, Oxfam, an international relief and development agency, follows

government guidelines for building simple pit latrines out of local materials, instead of

using imported concrete. As a first step, open defecation should be restricted to agreed areas outside the

emergency settlement, away from where local people live, and at least 50 metres from

drinking water sources. Separate areas should be set aside for men and women. Facilities

for hand-washing need to be provided nearby. Drainage channels may need to be dug to stop

excreta from being washed towards water sources. Excreta deposited in the open must be covered with soil to prevent smells and flies. If

open fields are used for defecation, excreta should be collected and disposed of in pits

and covered over. Alternatively, trenches can be dug for people to defecate in. Trenches

need to be kept clean and covered over with soil each day. Both systems - open defecation

or trenches - require a large workforce who may need payment. Workers should be provided

with equipment such as rakes, shovels and buckets, and protective clothing such as

overalls, gloves and boots. They will also need facilities for changing out of soiled

clothes and washing them. Controlled open defecation often goes against previous social habits. To work well. it

requires the full co-operation of the community and monitoring to make sure that the

system is working. As soon as possible after the emergency settlement has been established, latrines

should be constructed, either on the basis of one latrine per family or one latrine for a

group of families. Latrines should be at least 20 metres away from sources of drinking

water, and pit latrines should not be sited uphill from wells or boreholes. Water

supplies in emergency settlements need to be monitored regularly for faecal pollution. Displaced people may already be familiar with using latrines, but lack of equipment or

materials to build latrines may be a problem. Organisations working in emergency

situations should keep supplies of picks, shovels and spades which can be used immediately

to dig latrines until local equipment can be bought. If materials for making squatting slabs and pit lining are available locally these

should be used otherwise local initiative may be undermined. Where such materials are

scarce, tools and moulds for casting concrete squatting slabs and pit lining blocks may be

required. While working with mobile displaced communities in Azerbaijan (in the former Soviet

Union) this year, Oxfam found that concrete slabs were popular and were kept clean and

covered when not in use. People dug new pits and re-used the slabs when they moved

locations. However, production of slabs was slow because the first moulds had to be

constructed from technical drawings. As a result, Oxfam has produced a kit of latrine

digging tools and a kit for casting concrete slabs. Each kit is designed to cope with the

needs of populations of 5,000 for two months. Oxfam keeps the kits in emergency

preparedness stores in several locations for rapid despatch. Latrines produced from this kit are not suitable for areas prone to flooding. However,

Oxfam has developed portable communal latrines for use in flooded areas**.

Based on the principle of a septic tank, sludge from excreta is kept for 8-10 days in a

sealed rubber tank during which time microbes reduce pathogens such as Vibrio cholerae to

a harmless level. The sludge is then emptied. Each of these latrines can serve the

sanitation needs of 1,000 people on a long-term basis. However they require at least 3,000

litres of water a day for flushing effluent between two tanks. Technical solutions to emergency sanitation must be accompanied by community

participation in decision making and sanitation education to bring about behaviour change.

People need to have the opportunity to question and advise and to maintain and manage new

systems.

Joy Morgan, Public Health Team, Emergencies Department, Oxfam, 274 Banbury Road,

Oxford, OX2 7DZ, UK. **The latrine was developed together with the University of

Surrey and the Cholera Research Laboratories in Bangladesh.

|

Another option: shallow trench latrines

In hot and dry climates defecation fields may be preferable to poorly

maintained latrines. Trench latrines will cope with immediate needs, as pointed out in the

refugee health supplement of DD45. A common

recommendation is to make a trench latrine 1 metre deep.

|

An alternative is to build a shallow trench with 'shelves' for the feet as

shown above. The trench is about 30cm deep in total. Each user covers his or her stools

with a small amount of soil. It is easier to dig than a deep trench, and each user has the

benefit of a fresh defecation site. Also, the excreta is deposited in a top layer of soil

where decomposition is fast

|

|

Eventually, plants and trees around will benefit from the

richer soil.

Uno Winblad

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 57 June-August

1994  5 Page 6 7 5 Page 6 7

Urban alternatives: the dry-box Uno Winblad describes a system that turns human excreta

into valuable fertiliser. Most common sanitation technologies today

cannot solve the problem of human excreta disposal for the fast growing population living

in informal or illegal settlements in developing country cities. Pit-based systems like the VIP latrine (see="#page4">page 4) and the

pour-flush latrine require a reasonable amount of space, soil that can be dug, and a low

groundwater level. Sewage systems are prohibitively expensive both to install and to run. They require

large amounts of water for flushing, pollute water sources and can only be effectively

applied where there is planned urban development. These technologies are all based on the idea of human excreta as an unpleasant and

dangerous waste product to be disposed of.

|

Side view of a dry-box latrine There may be situations where this waste approach is appropriate, but all too often it

is not. For urban areas in particular, alternatives are required based on the concept of

human excreta as a resource. Such alternatives must be feasible to install in existing

built-up areas. Their investment costs should be low and they must operate without water

and without polluting the environment. The dry-box latrine(1) is such an alternative. It is based on the

resource approach. Under favourable circumstances human faeces will gradually decompose

and turn into a rich organic soil. In the process the volume is reduced and pathogenic

organisms destroyed. The decomposition is carried out by a variety of organisms including

bacteria and fungi. Bigger organisms like sowbugs and cockroaches feed on the

micro-organisms and on each other. They also play a role in mixing, aerating and breaking

up the faeces.

|

In a pit or a vault decomposition is hampered because urine and faeces are mixed

together. The mixture turns watery, liquid accumulates, the pit or vault rapidly fills up,

lack of oxygen slows down decomposition and results in foul smells, and there is likely to

be intensive fly breeding. The dry-box system avoids these problems by separating urine and faeces and by not

adding any water to the pit or vault. An example of a latrine based on the dry-box concept

is the Letrina Abonera Seca Familiar (LASF) developed by CEMAT (2) in

Guatemala. It has been promoted throughout Central America by UNICEF. The LASF is normally built above ground. Its receptacle consists of two vaults, each

with a volume of 0.6m (3). On top of the receptacle there is a movable

seat with a urine collector, or alternatively there is a fixed seat above each vault. From

the collector the urine flows via a pipe into a soakpit. Compost is removed via ground

level openings, normally covered by hatches.

|

Building

the two vaults over which a movable seat is placed

After using the latrine the user sprinkles ashes, soil or a soil/ lime mixture over the

faeces. The vault thus receives only faeces, ashes or soil/ lime plus paper or leaves used

for anal cleaning. (Compostable kitchen and garden refuse is not put in the vault as it

contains too much water.)

|

|

Every week the contents of the vault should be stirred with a stick and more ashes

added. Urine is infiltrated into a soakpit under the latrine or collected in a jar,

diluted with 4-5 parts of water and used as a fertiliser. When the first vault is nearly full it should be topped up with soil and the opening in

the platform closed. The second vault should now be used. A year later, or when the second

vault is nearly full, open and empty the first vault. It will by now contain about 250kg

of relatively safe compost (3). Over the past 15 years thousands of LASF

units have been built in Central America, in urban as well as in rural areas. Many of them

are functioning well. There are also examples of LASF units not functioning so well. This

is due to poor implementation with insufficient promotion, training and follow-up rather

than the dry-box concept. Of particular interest is the urban application of the dry-box concept. Hermosa

Provincia is a low-income, high density barrio in El Salvador's capital city. Here all the

130 households built LASF latrines three years ago. There is little space between the

houses and sometimes no backyards. The LASF is therefore usually attached to the house,

sometimes even placed inside the house. All the units in Hermosa Provincia are functioning extremely well. As ash is not

available in sufficient quantities, households sprinkle a mixture of sawdust and lime over

the faeces. The compost is used to reclaim wasteland or put in bags and sold. The contents

of a vault fetch the equivalent of about US$ 10 (4). The cost of a LASF unit in Central America is currently the equivalent of US$ 60-80 for

material and transport plus the cost of self-help

labour, training and follow-up.

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 57 June-August

1994  6 Page 7 8 6 Page 7 8

The following lessons can be learnt from the LASF experience in Central

America:

- There are no technological barriers to widespread application of the dry-box system for

human excreta disposal. The system can be used in crowded urban areas as well as on farms

and in small rural communities.

- The main barrier is the common attitude that the dry-box represents an inferior

technology fit only for the poor.

- A dry-box latrine is more sensitive to misuse and neglect than a pit latrine. It is

therefore particularly important that dry-box users participate in decision making and

training and receive follow-up support.

- As the contents of the vault must be kept dry, the system is less feasible where people

use water for anal cleaning.

|

Dry-box LASF latrines in a central American city Current research includes attempts to simplify the technology, lower unit costs and

develop prefabricated, high performance, upmarket models. More research is required on the handling of 'grey' water (dish or bath water) where

there is a piped water supply but no sewers. Another important focus for action research is the development of dry-box systems for

households using water for anal cleaning.

|

The real significance of the dry-box approach lies in its implications for urban

ecology and municipal economy: less environmental pollution; reduced water consumption; no

need for sewers and sewage treatment plants; and finally, the creation of a valuable

resource for urban food production and wasteland development. Uno Winblad, Pataholm 5503, 384 92 ALEM, Sweden 1 The term 'dry' is often used for any non-flush sanitation system.

Dry-box is more specific and refers to completely dry systems such as the Vietnamese

double-vault latrine, the Yemeni long-drop latrine, the Ladakhi latrine and the LASF:

2 CEMAT stands for Centro Mesoamericano de Estudios sobre

Tecnologia Apropriada, an NGO based in Guatemala city.

3. Studies by CEMAT indicate that after about 8 months of storage

there is a rapid decline in Ascaris eggs, reaching 0 after 10-12 months. Harmful bacteria

are less hardy than Ascaris eggs and are not likely to survive in conditions where Ascaris

eggs cannot.

4. Price as at April 1993. Editors' note: All sanitation technologies have strengths

and weaknesses. One possible weakness of the dry-box latrine, identified in practice, is

that users need to be motivated to ensure that urine and faeces are separated. The

standard design may be more difficult for women and small children to use than it is for

adult men. Therefore to work well, the dry-box latrine requires substantial promotion,

training and follow-up.

|

Further reading on sanitation Boot M., and Cairncross S., (eds), 1993. Actions speak -The study of hygiene

behaviour in water and sanitation projects. Price: US$ 32 (discount available to people in

developing countries). Available from. IRC, PO Box 93190, 2509 AD, The Hague, The

Netherlands. Srinivasan, L., 1990. Tools for community participation: A manual for training

trainers in participatory techniques. (Available in English, French and Spanish.) PROWWESS

/ UNDP. Price: Manual US$ l7.95; Video US$ 32.00; Both US$45.95. A limited number of

manuals can be provided free to people and organisations who cannot afford them. Please

write and explain how you would use the manual. Due to financial constraints PACT cannot

guarantee to meet every request. Available from: PACT 777 United Nations Plaza, New York,

NY 10017, USA. WHO, 1985. Achieving success in community water supply and sanitation projects.

Price: Sw. Fr 7 or US$ 5.60 (30 per cent discount offered to readers in developing

countries) Available from: WHO Distribution and Sales, CH-1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland.

Readers in WHO's south-east Asia region can order the manual for 20 Rs (Indian)

from: WHO Regional Office for South East Asia, World Health House, New Delhi

110-002, India. Winblad, U, and Kilama W, 1985. Sanitation without water. Macmillan,

Basingstoke.

Price:£4.00. Available from TALC, PO Box 49, St Albans, AL1 4AX, UK. For more information about free publications on sanitation write to

AHRTAG.

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 57 June-August

1994  7 Page 8 7 Page 8

A picture of hygiene Education on the importance of handwashing after using the toilet is usually done in

words. However, in schools in our region we have introduced the practice of hanging a

calabash or other available container outside the toilets. The students fill the container

with water every morning. They wash their hands by tipping the container over so that

water can flow out a small hole in the bottom, just like in the tippy-tap described in DD54. I think that when organisations print health education

posters or leaflets showing toilets, they should include a picture of a handwashing

container attached to the toilet to remind people of the connection between handwashing

and sanitation. Dr Massimo Serventi, Paediatrician, Dodoma General Hospital, Tanzania.

Peer communication best In Burundi, in central Africa, a new hygiene education programme has shown that="#***">peer education by trained neighbours is an effective way of changing

behaviour. In the programme voluntary teams of community members - at least half of them

women - are given training in making household visits and organising group meetings. They

practise discussing with, and listening to, people. Forty per cent of households are chosen for personal visits. During these visits,

practices in the household are discussed and links between unhygienic practices and

disease is explained. Householders are asked to identify possible ways of improving

hygiene. The other 60 per cent of households are invited to participate in monthly group

meetings. A poster series showing current and proposed practices is used as a visual

support during the visits and group meetings. Leaflets with the same pictures and messages

are then distributed and discussed. Motivation of volunteers is achieved by giving them educational aids such as T-shirts

and giving awards for achievements. Evaluation - through observations and focus group discussions - has shown improved

practices at household level. In addition, the communication style of volunteers had

improved markedly. They no longer communicate by 'telling' community members what to do;

instead they encourage people to analyse their own situation and find appropriate

solutions. Marjolein Dieleman, Frans de Groot and Constantin Nahayo, Ministère de la Santé

Publique, BP 4351, Bujumbura, Burundi.

*** Peer education is based on the idea that often people

learn best from people of similar backgrounds and ages to themselves.

Prevention: where to start? A recent UN publication stated that food-borne infections may cause up to 70 per cent

of episodes of diarrhoea in developing countries. Other publications emphasise water-borne

transmission. Obviously many factors are related: unhygienic sanitation can result in water-borne

disease, and lack of handwashing contributes to food-borne diarrhoea. However, assuming

one cannot change all behaviours in the short term, where should a project begin in trying

to reduce diarrhoea? Walter Bray, Director, Find Your Feet, 37-9 Great Guildford Street, London SE1 0ES,

UK.

Dr José Martines, CDD, WHO replies: Mr. Bray is correct in stating that many factors are related to the incidence of

diarrhoea. His question about where to start in seeking to reduce diarrhoea is, therefore,

complex. Where to begin depends on the local conditions. These include what the local community

considers as priorities, current hygiene behaviours, and existing facilities (such as

water sources and sanitation facilities). Scientific information about the effectiveness of various interventions can certainly

assist that choice, but it is not the only consideration. In addition, it is important to

assess the feasibility of introducing specific interventions, and to compare the

effectiveness of an intervention with its cost. The figure Mr. Bray quotes for food-borne transmission of diarrhoea is at the top end

of the range. It is estimated that improving food hygiene could result in a reduction of

between 15 and 70 per cent of diarrhoeal episodes. The range is very wide, reflecting the

lack of solid information about the effectiveness of improving food hygiene. It is also estimated that improving water supply may reduce the incidence of diarrhoea

by 16-37 per cent, while improving hygiene behaviour related to water and sanitation may

reduce incidence by 14-48 per cent. Other interventions such as the promotion of breastfeeding and measles immunisation

will have a lower impact (about 5 per cent) on the general incidence of diarrhoea, but are

likely to be particularly effective against more life-threatening forms of diarrhoea. In most settings the following preventive interventions should be considered: measles

immunisation, promoting breastfeeding, and hygiene education linked to improving water

supply and sanitation.

|

Scientific editors Dr Katherine Elliott and Dr William Cutting

Executive editor Kate O'Malley

Managing editor Kathy Attawell

Design & production Ingrid Emsden

Editorial advisory group

Professor A G Billoo (Pakistan)

Professor David Candy (UK)

Dr Shanti Ghosh (India)

Dr Michael Gracey (Australia)

Dr Adenike Grange (Nigeria)

Dr Nicole Guérin (France)

Dr Norbert Hirschhorn (USA)

Dr Sharon Huttly (UK)

Dr Claudio Lanata (Peru)

Dr Jon Rohde (USA)

Dr Mike Rowland (UK)

Professor Dang Duc Trach (Vietnam)

Professor Andrew Tomkins (UK) With support from AID (USA), Charity Projects (UK),

Ministry of

Development Cooperation (Netherlands), ODA (UK), UNICEF, WHO Publishing partners

BRAC (Bangladesh)

CMAI (India)

CMU (China)

Grupo CID (USA)

lmajics (Pakistan)

National Institute of Hygiene and Epidemiology (Vietnam)

ORANA (Senegal)

RUHSA (India)

Turkish Medical Association (Turkey)

Consultants at University Eduardo Mondlane (Mozambique)

|

Issue no. 57 June - August 1994

Page Navigation

This edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online is produced by Rehydration Project. Dialogue on Diarrhoea was published four times a year in English, Chinese, French, Portuguese, Spanish, Tamil,

English/Urdu and Vietnamese and reached more than a quarter of a million readers worldwide. The English edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea was produced and distributed by Healthlink Worldwide. Healthlink Worldwide is committed to strengthening primary health care and

community-based rehabilitation in the South by maximising the use and impact

of information, providing training and resources, and actively supporting

the capacity building of partner organisations. - ISSN 0950-0235 Reproducing articles

Healthlink Worldwide encourages the reproduction of

articles in this newsletter for non-profit making and educational uses. Please

clearly credit Healthlink Worldwide as the source and, if possible, send us a copy of any uses made of the material.

|

updated: 23 August, 2019

|