|

| |

Shigellosis

Clinical Update: A supplement to Issue no. 44 - March 1991

pdf

version of

this Issue version of

this Issue

|

There is much information in this issue that is valuable

and useful. Online readers are reminded, however, that treatment guidelines and health

care practices change over time. If you are in doubt, please refer to

WHO's up-to-date Dehydration Treatment

Plans.

|

Pages 1-4 Shigellosis

A supplement to Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online Issue 44

- March 1991

|

DDOnline Shigellosis

supplement to DD44  Page 1 2

Page 1 2

Clinical Update

SHIGELLOSIS

Shigellosis, or 'baciliary dysentery', is an intestinal infection that is a major

public health problem in many developing countries, where it causes about 5 to I0 per cent

of childhood diarrhoea. This special DD insert provides an overview of

shigellosis, including cause, effect and treatment.

Shigellosis is characterised by the frequent and painful passage of stools that consist

largely of blood, mucus and pus, accompanied by fever and stomach cramps.

|

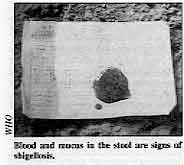

Blood

and mucus in the stool are signs of shigellosis.

In some developing countries more people die from shigellosis than from watery

diarrhoea. As many as 25 per cent of all diarrhoea related deaths can be associated with

Shigella.

|

What causes shigellosis? The symptoms of shigellosis result from infection with the Shigella bacterium. Two of

the four species of Shigella are common in developing countries. Shigella flexneri is

endemic (present at all times) in most communities. Shigella dysenteriae type 1

often occurs in an epidemic pattern; the organism can be absent for a number of years,

only to reappear and infect a large proportion of the population. These two species of

Shigella generally produce the most severe illness. In developed countries Shigella

sonnei is the most common and is the least virulent Shigella bacterium. Shigella

boydii causes disease of intermediate severity and is least common of the four, except

in the Indian sub-continent. Who gets shigellosis, and how common is it? Shigellosis is found throughout the world, mostly in children aged under five. Rates of

Shigella infection are highest where sanitation is poor. They are also influenced by

nutritional status, and environmental factors affecting transmission such as rainfall and

temperature. Shigella infections can occur throughout the year, but in most communities

the incidence is highest when the weather is hot and dry. This may be because the scarcity

of water limits handwashing and other hygiene measures that reduce transfer of the very

small number of bacteria needed to cause infection. Health workers are usually aware of the number of shigellosis cases, because symptoms

are severe, and therefore children with Shigella infections are more likely to be brought

to hospitals or clinics. Case fatality rates, even in hospitalised cases of dysentery, are

six to eight times greater than for watery diarrhoea. Dysentery is associated with

persistent diarrhoea. In rural north India, for example, nearly a third of all persistent

diarrhoeal episodes are dysenteric. During disease epidemics caused by Shigella dysenteriae type 1, as many as one

in ten people in affected communities will become infected, and as many as 10 to 15 per

cent of these will die. At the Diarrhoea Treatment Centre of the International Centre for

Diarrhoeal Disease Research in Bangladesh (ICDDR, B), over 700 patients a year with

shigellosis are admitted to an in-patient unit. Ten per cent of these patients die while

in hospital.

|

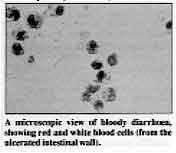

A microscopic view of bloody diarrhoea, showing red and white

blood cells (from the ulcerated intestinal wall).

Although these are patients with the most severe illness, their high mortality rate

shows the difficulties in treating patients with shigellosis, especially when they come

for care late in the course of the illness. Young children and elderly people are most

likely to die from the effects of shigellosis.

|

|

At the ICDDR, B Treatment Centre, children under 12 months of age account for 21 per

cent of shigellosis admissions but up to 33 per cent of all fatal cases. Dysentery is

especially severe and more likely to be fatal in young infants, the malnourished, children

who are not breastfed, and following measles. Acute and particularly prolonged episodes of

dysentery often change marginal malnutrition to overt protein energy malnutrition, and can

lead to vitamin A deficiency. What are the effects of Shigella infection? Shigella infect the cells of the lining of the large intestine (colon). The bacteria

invade and damage these cells, producing breaks (ulcers) in the mucous membrane lining the

intestine.

|

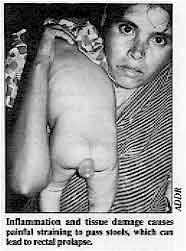

Inflammation and tissue damage causes painful straining to

pass stools, which can lead to rectal prolapse. These ulcers are most common in the rectum, which is the lowest part of the large

intestine. Ulceration of the intestinal lining results in increased production of mucus,

and the loss of blood and serum proteins into the intestinal cavity. This causes the

symptoms of dysentery, which include blood and mucus in the stool (bloody diarrhoea);

fever is also common.

|

The effects of Shigella infection on the intestine usually differ from those of

organisms such as enterotoxigenic E. coli and Vibrio cholerae, which cause

watery diarrhoea, without fever. These organisms infect only the small intestine and cause

little or no damage to the cells lining the intestine. Dehydration is the main

complication resulting from these infections. Occasionally Shigella causes only watery

diarrhoea and this will cause dehydration (unless appropriate rehydration fluids are

given). Shigella dysentery may also lead to a number of dangerous complications. These include:

- severe anorexia (loss of appetite)

- hypoproteinaemia (a low concentration of blood protein)

- hyponatraemia (a low concentration of blood sodium)

- dilation of the large intestine

- seizures

- anaemia

- kidney damage

- persistent diarrhoea

- weight loss and malnutrition

Produced by Dialogue on Diarrhoea and the Applied Diarrhoeal Disease Research Project

(ADDR), Harvard Institute for International Development, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA

|

|

DDOnline Shigellosis

supplement to DD44  1 Page 2 3 1 Page 2 3

How can shigellosis be identified?

- Stool culture

The most accurate way to find out if a person with diarrhoea is infected with Shigella

is to make a culture of the stool, to check if the bacterium is present. But this is often

impractical in developing countries. Making a culture is expensive and facilities are

often unavailable in the rural communities and urban slums where the incidence of

shigellosis is greatest. Moreover, the results are usually only available after two or

three days, and treatment should not be delayed - a decision regarding antibiotic use must

be made immediately. Stool microscopy for pus cells to identify shigellosis is not

necessary when visible blood is present in stools. It may help to identify cases of mild

shigellosis, when stools are mucoid without blood, but this is too non-specific to be of

any practical value.

Shigella bacteria are not always found in the stool cultures of children who are infected.

Even in the best conditions, a stool culture may only identify about 70 per cent of those

infected. If antibiotics are given to children with shigellosis before they come to the

clinic, the drugs may eliminate the bacteria from their stools. In most studies that have

been conducted in developing countries, Shigella were recovered from a stool culture in

half or more of all children who had dysentery (see Table 1).

Table 1: Percentage of stool culture showing positive

for Shigella

taken from children with dysentery |

Study site

(community and hospital based) |

Year of study |

Per cent of cases

showing Shigella |

| Dhaka, Bangladesh |

1979 |

55 |

| Nonthaburi, Thailand |

1986 |

44 |

| Rangpur, Bangladesh |

1988 |

50 |

| Bangkok, Thailand |

1991 |

37 |

- Clinical signs and symptoms

The use of clinical signs and symptoms is therefore very important in identifying

patients with shigellosis. Dysentery (bloody diarrhoea) is a very reliable indicator of

the infection in the majority of cases. In many developing countries Shigella infection is

the most common, and potentially the most severe, cause of dysentery. After Shigella, Campylobacter

jejuni and Salmonella are the next most common causes of dysentery, but these

usually produce self-limited illness that is rarely as serious or life-threatening as

shigellosis. The parasite Entamoeba histolytica, responsible for amoebic dysentery,

is a rare cause of dysentery in children, accounting for less than 5 per cent of all

episodes. Stool microscopy for protozoa may not be available and it is often unreliable.

Amoebiasis can only be diagnosed with certainty when trophozoites of E. histolytica containing

red blood cells are seen in fresh stools. The microscopic detection of cysts alone is not

sufficient for a diagnosis of amoebiasis. Treatment of dysentery should therefore focus on

the management of shigellosis. Mothers are usually accurate observers of their children's

stools. If a mother reports that her child's stools contain blood and mucus, then it is

reasonable to assume that the child is infected with Shigella. Many communities have local

terms used to describe different types of diarrhoea, including dysentery, and health

workers should become familiar with these terms.

|

|

DDOnline Shigellosis

supplement to DD44  2 Page 3 4 2 Page 3 4

Treatment of shigellosis in children Children with visible blood in stools should be presumed to have shigellosis and be

treated accordingly. The key components of shigellosis treatment are:

- giving an effective antibiotic

- continued feeding

- replacement of fluid losses

- follow up

Children treated early in their illness with an appropriate antibiotic will be

considerably better 48 hours after therapy has begun. Those who do not receive effective

drug treatment may develop persistent diarrhoea, malnutrition, and other life-threatening

complications. Those who are infected with Shigella who are already malnourished need special

attention, as do infants under 12 months old, and those already dehydrated. The most

severely ill should be cared for in hospital and the others should be followed up at least

once every 48 hours until they are better. Infection of the bloodstream is common in these

patients, and is caused by bacteria, other than Shigella, normally found in the gut. The

signs of bloodstream infection are shock, low urine output and lethargy. Intravenous

antibiotics such as gentamicin and ampicillin should be given in addition to an oral

antibiotic for treatment of shigellosis. However, if ampicillin is given intravenously, it

should not also be given orally.

- Antibiotic treatment

Antibiotic treatment should be started as soon as acute dysentery is identified. The

chosen drug must be safe for use in children and inexpensive; a liquid formulation is

preferable but not essential. Most strains of Shigella in the community must be sensitive

to the drug, and it should have been shown to be effective in controlled clinical trials.

Ampicillin and cotrimoxazole fulfil these criteria, and for the last 15 years have been

the drugs of choice for treatment of shigellosis. Some doctors wrongly prescribe

metronidazole, believing that the drug will cure both shigellosis and amoebic dysentery.

Metronidazole should be used only if E. histolytica has been positively

identified, or if treatment for shigellosis has failed.

|

Table 2: Appropriate

antibiotics for shigellosis

|

| Antibiotic (1) |

Children |

Adults |

Comments |

Cotrimoxazole

(also called trimethoprim (TMP) - sulfamethoxazole (SMX) |

TMP 5mg/kg and SMX 25mg/kg twice a day for 5 days |

TMP 160mg and SMX 800mg twice a day for 5 days |

Not recommended for use in jaundiced and premature infants under 1

month old |

| or: |

| Ampicillin |

25mg/kg 4 times a day for 5 days |

1g 4 times a day for 5 days |

Safe for infants, and pregnant or lactating women |

| Alternative if Shigella in the local area are

resistant: |

| Nalidixic acid |

15mg/kg 4 times a day for 5 days |

1g 3 times a day for 5 days |

Not recommended for infants under two months |

1. All doses are for oral

administration. If a liquid form of the drug is not available for children, give the approximate

dose as crushed tablets.

|

|

Recently, however, resistant strains of Shigella have become common in some countries,

such as Bangladesh. Where resistance to ampicillin and cotrimoxazole exceeds 25 per cent,

nalidixic acid is used as an alternative (see="#Table 2">Table 2). This drug

is more expensive than cotrimoxazole and ampicillin but is similarly effective.

Unfortunately, in areas where nalidixic acid is widely used, Shigella bacteria often

rapidly become resistant. It is important to use these drugs carefully to minimise the

problem of resistance. Their use should be restricted to patients with dysentery: patients

with watery diarrhoea do not require an antibiotic unless cholera is suspected. Health

workers need to know the resistance pattern of Shigella in their community in order to

make the right decision about which drug to use. Stool cultures should be obtained on a

regular basis, and isolates of Shigella tested for sensitivity to drugs commonly used for

treatment. The new fluoroquinolines (e. g. ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin) are highly active and

clinically effective when given by mouth, but because they cause cartilage damage in young

animals, there is still concern about their safety in young children. Studies are being

carried out to determine how important this is in humans. Antibiotics known to be less

effective and therefore not recommended include neomycin, gentamicin, the first generation

cephalosporins, kanamycin, amoxycillin and sulphaguanidine. In many parts of the world, a

significant proportion of Shigella strains show in vitro sensitivity to

furazolidine and many doctors who use it as initial therapy in India report anecdotal

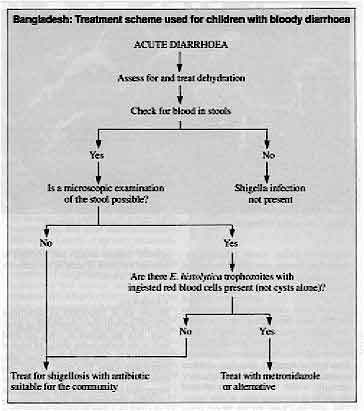

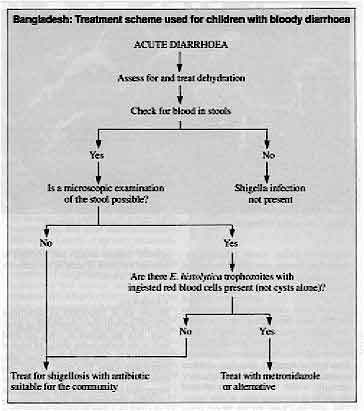

favourable results. However, controlled clinical trials are lacking. The diagram below shows a scheme which was developed for health workers to use when

treating children with bloody diarrhoea in Bangladesh. Similar schemes could be

established and evaluated for other countries.

|

|

Bangladesh: Treatment scheme used for children with bloody diarrhoea

ACUTE DIARRHOEA

- Assess for and treat dehydration

- Check for blood in stools

- Yes No

- Is a microscopic examination of the stool possible?

- Shigelli infection not present

- No Yes

- Are there E. histolytica trophozoites with ingested red blood cells present (not

cysts alone)?

- No Yes

- Treat for shigellosis with antibiotic suitable for the community

- Treat with metronidazole or alternative

|

|

DDOnline Shigellosis

supplement to DD44  3 Page 4 3 Page 4

- Continued feeding

Nutrient absorption continues during shigellosis, because the disease does not affect much

of the small intestine, where most absorption takes place. However, the inflammation in

the large intestine affects nutritional status. Early effective antimicrobial therapy

cures the infection and inflammation and the child's appetite will return, soon followed

by weight gain. It is important to feed and/or breastfeed patients with shigellosis

frequently to prevent them developing hypoglycaemia (low blood sugar) and losing weight

during their illness. This can be difficult because they are often severely anorexic

(suffering from loss of appetite). However, children need not eat as much at each feeding

as they normally would. Small amounts of food should be given every three to four hours.

This will also keep up the blood sugar level. Foods rich in potassium, such as bananas,

are recommended. One extra meal should be given to the child every day for at least two

weeks after the diarrhoea stops.

Continued feeding also helps to prevent the acute weight loss that occurs during

diarrhoea. If a severely ill patient in hospital refuses to eat or to breastfeed, it may

be necessary to feed with a nasogastric tube initially.

- Replacement of fluid losses

Mild to moderate dehydration is common in patients with shigellosis. Dehydration is

caused by loss of fluid in stools, evaporation of water through the skin due to fever, and

reduced fluid intake because of anorexia. Hyponatraemia (low levels of sodium in the

blood) is a particular problem for those infected with S. dysenteriae type

1. Oral rehydration therapy should be given and in most cases fluids do not need to be

given intravenously. Giving intravenous fluids increases the risk of infection and is

expensive. Oral rehydration solution contains enough salt (sodium) to increase the level

of salts in the patient's blood, if it is low.

- Follow up

Follow up is important to determine whether patients have responded to treatment. Ask the

mother to bring her child back to the health centre within 48 hours if the child is less

than one year old, dehydrated when first seen, or still has blood in the stool. Diarrhoea

may take longer than two days to stop altogether, but the visible blood in stools should

disappear within that time. If the blood does persist, the child may be infected with a

strain of Shigella that is resistant to the drug used. Such patients should be treated

with a different agent for shigellosis unless another cause of dysentery is found. If

there is still no improvement after two days of treatment with an alternative drug, the

child should be taken to hospital. Amoebiasis should be considered.

How can shigellosis be prevented?

Shigella bacteria infect only humans and monkeys, and do not survive for long outside

the body. Therefore, for infection to occur, Shigella bacteria must pass quickly from one

person to another. This usually occurs through 'faecal-oral' transmission. This takes

place when a person with shigellosis defecates, does not wash his or her hands adequately

afterwards, and transfers Shigella germs to food (or water). The bacteria are then

swallowed when the contaminated food is eaten by another person.

|

Handwashing after defecation is the best way to prevent the

spread of shigellosis.

Fewer than ten ingested bacteria are enough to cause a Shigella infection; in contrast,

thousands of Vibrio cholerae are required to cause disease.

|

Once a member of the family has dysentery, infection can spread from person to person

very quickly. Community health education must include information on hygiene. The most

effective way to reduce the incidence of shigellosis is to ensure proper washing of hands

following defecation, and adequate disposal of faeces. It is not only adults who need to

wash their hands. Children are probably the most common carriers of infection, and they

must also be shown how to wash their hands. Adults caring for children need to wash their

hands often too. Even if soap is not available, a good scrubbing with water, and use of an

abrasive such as sand, is helpful in reducing the spread of infection. Household food and

water also have to be protected from faeces and unwashed hands. There are no effective

vaccines for the prevention of shigellosis, although research into vaccines, especially

ones for oral use, is being carried out.

Steps to eradication Of all the diarrhoeal illnesses, shigellosis is the one most closely linked with

underdevelopment. Features of underdevelopment that produce a high incidence of

shigellosis include poor housing and insanitary conditions, overcrowding, absence of

adequate water supplies for cleaning and washing, and childhood malnutrition. In all

countries where economic and social conditions have improved, the most virulent forms of

shigellosis, caused by Shigella dysenteriae type 1 and Shigella flexneri, have

virtually disappeared. Thus the prevention of shigellosis is closely linked to efforts to

improve the economic and social conditions of people living in areas where shigellosis is

now endemic. On a national level, Diarrhoeal Disease Control Programmes need to research patterns of

antibiotic use, investigate resistance of Shigella strains to drugs in different regions,

develop treatment schemes appropriate for local conditions, and train doctors in the

correct case management of dysentery. Acknowledgements This supplement is based on material prepared by Drs M Bennish and J Griffiths of

the New England Medical Center (Tufts University), Dr A Salam of the International Centre

for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh and Dr M Bhan, of the All-India Institute of

Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India; and developed by the ADDR Project, Harvard Institute

for International Development.

Produced by Dialogue on Diarrhoea, AHRTAG, UK, and the Applied Diarrhoeal Disease

Research Project (ADDR). Harvard Institute for International Development, Cambridge, MA

02138. USA

|

Shigellosis

Clinical Update - A supplement to Issue no. 44 March 1991

Page Navigation

This edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online is

produced by Rehydration Project.

Dialogue on Diarrhoea was published four times a year in English,

Chinese, French, Portuguese, Spanish, Tamil, English/Urdu and Vietnamese and

reached more than a quarter of a million readers worldwide.

The

English edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea was produced and distributed by

Healthlink

Worldwide.

Healthlink Worldwide is committed to strengthening primary health care and

community-based rehabilitation in the South by maximising the use and impact

of information, providing training and resources, and actively supporting

the capacity building of partner organisations. - ISSN 0950-0235 Reproducing articles

Healthlink Worldwide encourages the reproduction of

articles in this newsletter for non-profit making and educational uses. Please

clearly credit Healthlink Worldwide as the source and, if possible, send us a copy of any

uses made of the material.

|

updated: 4 March, 2016

updated: 4 March, 2016

|

version of this Issue