|

| |

Refugees and Displaced Communities

Health Update: A supplement to Issue no. 45 - June 1991

pdf

version of

this Issue version of

this Issue

|

There is much information in this issue that is valuable

and useful. Online readers are reminded, however, that treatment guidelines and health

care practices change over time. If you are in doubt, please refer to

WHO's up-to-date Dehydration Treatment

Plans.

|

Pages 1-6 Refugees and Displaced Communities

A supplement to Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online Issue 45

- June 1991

|

DDOnline Refugees

and Displaced Communities supplement to DD45  Page 1 2

Page 1 2

Health Update REFUGEES AND

DISPLACED COMMUNITIES

Diarrhoeal disease is one of the major causes of illness and death among refugees.

In this insert, Dialogue on Diarrhoea assesses the special needs of communities

in refugee camps; provides practical guidelines for protecting water sources, improving

sanitation and ensuring good hygiene to prevent outbreaks of disease; and describes

measures to control cholera.

There are more than 30 million refugees or displaced people in the world. Death rates

in refugees and those displaced by natural disasters are often extremely high. especially

in the early phase of displacement. In Ethiopia in 1985 and in the Sudan in 1988,

mortality rates in camps for displaced people were 60 times greater than in non-refugee

communities. particularly among children. In Bangladesh, a diarrhoea epidemic with 12,000

acute cases quickly developed amongst people who had been made homeless by the cyclone

'Urirchar' (1).

|

The danger of diarrhoea in refugee camps - a Kurdish child

drinks dirty water from a makeshift container.

People who remain in areas affected by war or other disasters face problems similar to

those forced to leave their homes: there is no sanitation infrastructure, and water

supplies are often contaminated.

|

In these situations immediate steps must be taken to protect people from the spread of

disease, including diarrhoea. Lives can be saved by effective treatment of diarrhoea and

dehydration. Adequate supplies of clean water and improvised sanitation facilities can

help to improve the health status of the community, and prevent diarrhoea. The refugee community A refugee community needs special attention because:

- people may have escaped from very difficult and traumatic situations;

- they may be in a weak physical state and under stress;

- over half the population may be under 15 years old, and women and the elderly may make

up most of the adult population, particularly during a war;

- the camp is often established on poor, previously unused land (because, for example.

there is poor water supply);

- the social structure of the community is damaged or destroyed;

- people are waiting for the time when they can return home and may be reluctant to put

time and effort into projects to improve their new 'home'.

Assessing the situation Refugee camps are usually crowded and may be very large. Some camps in Ethiopia and

Sudan have up to 150,000 residents - the size of a large town. Early on, when a refugee camp is being established, public health problems such as

rubbish control, sanitation and hygiene may seem less important than immediate day-to-day

needs - for food, water supplies and curative health services. However, the longer a camp

is in existence, the greater the risk that the environment will become polluted, unless

prompt action is taken. Once a refugee camp is established, it is important to find out

about the local water supply, and sanitation and hygiene needs, before deciding on any

action.

|

|

DDOnline Refugees

and Displaced Communities supplement to DD45  1 Page 2 3 1 Page 2 3

Water

|

In this refugee camp in Malawi, clean water is piped to the

community from large, temporary storage tanks.

The community needs as plentiful a supply of water as possible. To start with, each

person needs a minimum of 5 litres per day. After a few days, at least 15 to 20 litres per

day should be provided, and preferably more. Clinics may require up to 60 litres a day for

each person served by the facility. Camp authorities need to know:

- what the existing water sources are;

- their distance from the camp;

- the quantities available:

- if water is available all year round;

- whether families have their own water storage containers.

|

|

Water sources should be assessed for possible faecal pollution and to find out whether

they are protected from contamination. The ways in which people store and use water should

also be noted, especially practices that could cause contamination at the water collecting

point, or within the household.

|

Making water safe for household use by chlorination This recipe makes a concentrated (stock) solution of the chemical, which can be used to

treat larger quantities of water. Do NOT drink or use this solution undiluted and keep it

out of the reach of children. To make up the concentrated solution, add 4 teaspoons (16 grams) of sodium

hypochlorite, OR 10 teaspoons of bleaching powder (40 grams) to one litre of water. Always add this concentrated solution to water, to ensure proper mixing, as follows:

| 1 litre water; |

3 drops stock solution; |

| 30 litres water: |

1 teaspoon stock solution |

| 4550 litres water: |

1 litre stock solution |

Treated water should be allowed to stand for half an hour before using.

|

Sanitation and hygiene Camp authorities need to find out about:

- community defecation habits, noticing in particular what children do;

- the type of latrines people are used to;

- the location of defecation areas, their distance from water sources, tents or houses,

and which people use them;

- where people wash themselves, their clothes and utensils;

- whether soap is available;

- customs regarding burial of the dead;

- where and how rubbish is disposed of;

- the type of soil in the area.

Priorities for action Providing water Access to water should be increased to the maximum possible. Using filtered water from

a well or spring is better than using surface water. It can be useful to appoint an

individual to take charge of keeping water sources well maintained. Drainage ditches

should be dug throughout the camp, and kept free from rubbish to ensure that storm water

does not pollute water sources or stagnate in pools. Protecting water sources:

|

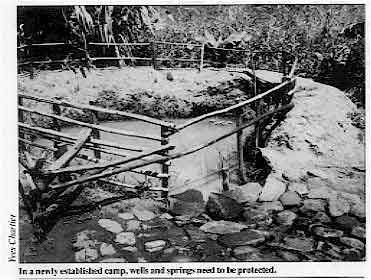

In a newly established camp, wells and springs need to be protected. Wells

- Fence off to keep animals away.

- Avoid use of household containers to take water from the well itself.

- Install a hand winch with an attached bucket; do not allow the bucket to touch the

ground.

- Assess drainage patterns for surface water and soil permeability to estimate the extent

of protection needed around the well.

|

|

- Make sure that potential sources of pollution (latrines, refuse pits) are located at

least 20 metres away and downhill (not uphill) from the well.

- Ensure good drainage around the well by installing a cement apron or digging surface

drainage canals.

|

|

DDOnline Refugees

and Displaced Communities supplement to DD45  2 Page 3 4 2 Page 3 4

Springs

- Build protective fences at least 30 metres up the slope to avoid contamination.

- Provide drainage for run-off (to the side of the spring to prevent erosion).

- Upgrade the spring with a small pipe (bamboo or plastic) to make collection of water

easier and to avoid contamination of spring water with soil.

- Use waste water that has drained downhill for washing, animals and irrigation.

- Build a 'spring box'. A small reservoir is dug at the spring source, and protected from

pollution with a box-like construction. Water is piped out of the reservoir for domestic

use.

|

Eventually, a 'spring box' can be built over the water source

to prevent pollution. |

Surface water (river or lake)

|

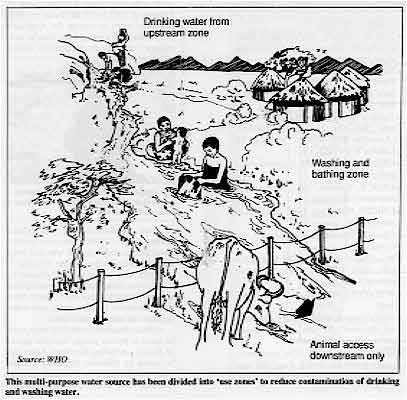

This multi-purpose water source has been divided into 'use zones' to

reduce contamination of drinking and washing water.

- Stop people from using the bank or shore for defecation by cutting down vegetation

cover, appointing 'water guards' and displaying picture signs.

- Create distinct use zones: upstream for the collection of drinking water; downstream for

bathing, washing, laundering; and further downstream for watering animals.

- Locate defecation 'fields' at least 50 metres away and downstream from use zones.

- Install a securely protected pipe in the drinking water zone to carry the water into the

community.

|

|

Water storage and purification

- Encourage families to collect and store water in clean, covered containers and to use a

special dipper, kept only for taking water from the container.

- If possible supply families with covered narrow necked vessels for water storage.

- Heat water to boiling point. Boil for several minutes (if fuel is available) if there is

any doubt about its quality, at least before it is given to young children to drink.

- Chlorinate domestic water if the chemicals are available and if water is not from a

centrally chlorinated, piped supply.

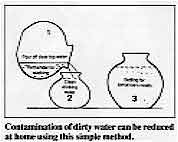

There are two simple ways in which contamination levels of polluted water can be

reduced (in the home) if purified drinking water is not available.

- If water cannot be chlorinated, leave for four to five hours in a transparent closed

container in sunlight. Ultra-violet radiation (in sunlight) will destroy the germs (2).

- Store water for 48 hours in a covered container. Dirt will settle in the bottom few

centimetres of water. Pour off the rest of the water into another vessel and use for

drinking. Use two large water storage pots in rotation. to provide a constant supply of

clean water (3).

|

Contamination of dirty water can be reduced at home using this

simple method.

- Pour off clear top water

- use remainder for washing

- Clean drinking water

- Settling for tomorrow's needs

|

|

|

|

DDOnline Refugees

and Displaced Communities supplement to DD45  3 Page 4 5 3 Page 4 5

Sanitation and hygienic waste disposal Sanitation is hard to provide when there is overcrowding. Many refugees may be from

rural areas and be unused to latrines, or may not be familiar with the problems of living

in a crowded environment. Alternatively they may be from urban centres and used to better,

less basic sanitation facilities. A large and unsettled population can create great waste

problems and sanitation facilities need to be set up as early as possible. Older children

can play a valuable role in helping their younger brothers and sisters to understand the

need for camp hygiene. Research from the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research in Bangladesh

emphasises the difference made by effective sanitation: refugee camps with piped water and

covered latrines had a cholera incidence rate of only 1.6 per 1,000 whereas in those

lacking facilities the rate increased to over four per 1,000 (4). Strategies for waste disposal Setting aside defecation areas

|

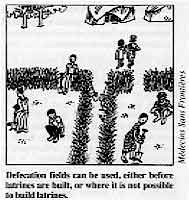

Defecation fields can be used, either before latrines are

built, or where it is not possible to build latrines. In hot and dry climates, defecation fields may be preferable to badly used and poorly

maintained pit latrines. Defecation fields should be at least 50 metres away from water

sources or houses, but near enough to be easily reached. Shovels should be available for

burying the faeces.

|

Building latrines

|

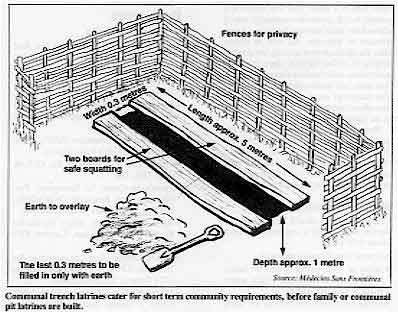

Communal trench latrines cater for short term community

requirements, before family or communal pit latrines are built.

One latrine should serve a maximum of 20 people. All latrines should be at least 20

metres from any water source, and at least ten metres from living areas. They must be easy

and pleasant to use, and safe for children.

|

|

Young

children should be encouraged to use the latrine.

|

- When the camp is first set up, trench latrines will cope with immediate needs.

- Pit latrines should eventually be built, especially in wet climates. Family latrines are

usually more acceptable than community latrines. However, camps are not usually planned to

take account of this, and there may not be enough space for each household to have its own

latrine.

- Communal latrines must be designed with people's beliefs and behaviours in mind. They

should be available in public places such as health centres or markets, and be easy to

clean and maintain. They should set an example for the camp. They need daily maintenance

as they can quickly become dirty.

|

ProperIy disposing of children's faeces

|

Children's stools, in particular, can be a source of diarrhoea

infection and need to be buried or put into a latrine.

The stools of children are potentially the most dangerous source of infection.

|

|

- Small children should be encouraged to use latrines, accompanied perhaps by older

brothers or sisters. until they are familiar with how to use them.

- Where children defecate on the ground, it is important to ensure that the faeces are

disposed of in latrines, or buried. In some camps, mothers have made small scoops which

they use to carry children's faeces away from living areas and clinics.

Disposing of solid waste

Rubbish control is important in refugee camps. Flies and rats spread infection from

rotting and contaminated waste.

- A communal collecting system can solve the problems of waste disposal.

- The market place should be located on the edge of the camp, so waste can be buried in

fenced landfill sites or burnt.

- Health centres produce dangerous wastes, which may attract children. These wastes must

be handled carefully and destroyed daily using an incinerator. The residue should be

buried in a deep, covered pit.

- Family waste can be disposed of in household refuse pits. These should be covered over

each day with a layer of soil to prevent infestation with vermin or attracting flies.

- Land covered in refuse, or used in the past as an uncontrolled defecation area could be

cleaned and converted into an area for other use, with a hard surface of. for example,

beaten earth. This gets rid of a source of infection and mobilises a group of people who

are then ready for future development activities.

|

Household rubbish can be buried in communal refuse pits, and

covered over with a layer of soil after each deposit. |

Disposing of waste water Household washing areas as well as water sources need safe drainage, because stagnant

and contaminated water presents a health risk, encouraging mosquitoes to breed, for

example. Waste water can be used in household and communal gardens.

|

|

DDOnline Refugees

and Displaced Communities supplement to DD45  4 Page 5 6 4 Page 5 6

Hygiene

- Many diarrhoeal diseases are directly related to poor hygiene. If plenty of water is

available, people are able to keep themselves and their surroundings clean, and the risk

of diarrhoeal transmission is substantially decreased.

- Latrines should be cleaned regularly to keep flies away.

- Food should always be prepared with clean utensils, kept covered and stored in a cool

place. Stored food should be thoroughly reheated before it is eaten.

- Handwashing, especially after defecation and before eating or preparing food, is

essential to prevent transmission of diarrhoea germs. Soap should be available if

possible.

Community education Health education plays a key role in refugee camps. In Somalia a few years ago, a

health worker responsible for cleaning in one camp agreed with the school teachers to give

a small prize to the child who killed most flies in a week. This was linked to a general

health promotion campaign which showed the links between faeces and transmission of

infection. As well as killing flies, the children were actively involved in helping to

collect rubbish, clean the camp and remind their families about the defecation areas and

handwashing before eating. The campaign successfully raised awareness about health issues

amongst the people in the camp.

|

Health education campaigns help people to be aware of the need

for hygiene.

Home visits and local meetings are important for discussing behaviours that improve

health. Health centres provide a forum for communicating health education messages to

women and children. Community leaders also play an important role.

|

|

Monitoring and evaluation Camp procedures should be monitored at regular intervals. It is important to check on

the following:

- general cleanliness of the camp:

- safety of water points (watch for faeces in the area, infiltration of surface water.

pools of stagnant water):

- latrine use (check that latrines are being used, and are clean and well maintained);

- record keeping of diarrhoeal disease incidence at the health centres (to facilitate

early recognition of epidemics).

These important public health measures to control the spread of diarrhoeal disease will

only be effective if people are able to take responsibility for their own living

conditions. Health workers and refugees should work together to find the most effective

approach in their situation. The main aim is to prevent outbreaks occurring by giving a

high priority to the public health measures mentioned above.

|

|

DDOnline Refugees

and Displaced Communities supplement to DD45  5 Page 6 5 Page 6

|

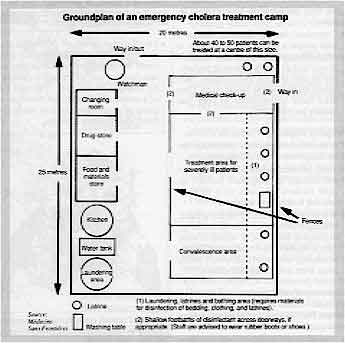

Epidemic cholera in refugee camps Cholera can spread very quickly in over crowded living areas. If an epidemic breaks

out: Control

- An emergency treatment facility should be established (see="#Groundplan">diagram).

- Apart from patients, people visiting the facility should be limited to those giving

care.

- Stored water for drinking should be purified with at least 0.2mg per litre of residual

chlorine.

- Sodium hypochlorite should be added to water at the following rates:

- 500mg per litre for washing;

- 2, 000mg per litre for cleaning walls and floors;

- 10, 000mg per litre for disinfecting contaminated bedding and clothes and for cleaning

latrines.

Public health measures

- Treat wells in the affected area; close them if possible. Appoint someone to treat each

collected bucket of water with sodium hypochlorite; ideally this should done at every well

when the water is collected.

- Health workers should regularly visit households in order to detect cases.

- Gatherings of people should be restricted.

- Carry out precautionary measures to reduce contamination of food sold in markets.

- Test samples of water for the presence of E. coli. This indicates faecal

pollution, and the possible presence of bacteria that cause diarrhoea. Send stool samples

for laboratory testing, if possible, to confirm the presence of cholera.

- Good record keeping (number of cases and deaths) at clinics and the treatment centre

will help in assessing whether the epidemic is getting worse, or whether public health

measures are having a positive effect.

- Use patient records to plot outbreaks on a map of the camp.

- Disinfect homes of patients if resources are available.

Groundplan of an emergency cholera

treatment camp

|

|

This insert was compiled using information from Yves Chartier (Médecins Sans

Frontières), Patricia Diskett (Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine and ex- Oxfam health

advisor) and UNHCR. 1. Toole M J and Waldman R J. 1990. Prevention of excess mortality in refugee and

displaced populations in developing countries. J. Am. Med. Assoc. vol 263. no

24:3296-3302.

2, UNICEF. 1984. Solar disinfection of drinking water and oral rehydration solution.

3. International Disasters Institute (now Relief and Disasters Policy

Programme, ODI). 1981. Disasters, vol 5. Practical supplements.

4. Khan M U. et al. 1982. Role of water and sanitation in the incidence of cholera

in refugee camps. Trans. R. Sac. Trop. Med. Hy g. 76: 373-7. Resources Sources of information

- International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), 17 Avenue de la

Paix, 1202 Geneva,

Switzerland.

- Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, Pembroke Place, Liverpool L3 5QA. UK.

- London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), Keppel Street. London WC1E 7HT.

UK.

- Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF). 8 Rue Saint-Sabin, 75011 Paris, France.

- Oxfam UK, 274 Banbury Rd, Oxford. OX2 7DZ, UK.

- Panafrican Centre for Emergency Preparedness and Response

(WHO/EPR). PO Box 3050, Addis

Ababa. Ethiopia.

- Save the Children, Mary Datchelor House, 17 Grove Lane. London SE5 8RD, UK.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Palais des Nations, 1211 Geneva

10, Switzerland.

- United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). 3 United Nations Plaza, New York, NY 10017,

USA.

- World Health Organization, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland.

Publications

- Cairncross S, Ross Bulletin No. 8. 1988. Small scale sanitation. (Available from

LSHTM.)

- Cairncross S and Feachem R, Ross Bulletin No.10. 1978. Revised 1986. Small wafer

supplies. (Available from LSHTM.)

- Cairncross S and Feachem R, (pub) John Wiley, 1983. Environmental health engineering

in the tropics: an introductory text.

- MSF, Paris, 1990. Practical guidelines on the purpose, selection and use of

disinfectants in refugee camps.

- MSF, Paris, 1988. Clinical guidelines., diagnostic and treatment manual.

- Morgan, P. Blair Research Laboratory. Ministry of Health, Harare. Zimbabwe, 1990. Rural

water-supplies and sanitation

- Oxfam. 1986. Practical guide for-refugee health care.

- Refugee Health Unit. Oxfam/Ministry of Health, Somali Democratic Republic, 1986.

Guidelines for health care in refugee camps.

- Save the Children, 1985. Establishing a refugee camp laboratory.

- Save the Children. 1987. Drought relief in Ethiopia., planning and management of

feeding programmes.

- Simmonds S. et al. Oxford University Press, 1983. Refugee community health care. (OUP,

Walton St. Oxford OX2 6DP. UK.)

- Tropical Doctor, Royal Society of Medicine 1991. vol. 21. sup. 1. Disasters. (Available

from RSM, 1 Wimpole St, London W1M 8AE. UK.)

- UNHCR, Geneva, 1989. Essential drugs policy.

- UNHCR, Geneva, 1982. Manual for emergency situations.

- UNICEF. New York. 1986. Assisting in emergencies.

- USAID. Washington. Water for the world.

- Windblad U and Kilama W. Macmillan Education, London, 1985. Sanitation without water.

- WHO/ EPR, 1991. African disaster handbook.

- WHO, Geneva, 1989. Coping with natural disasters: the role of local health personnel

and the community.

- WHO, Geneva. 1990. The new emergency health kit (listing drugs and supplies needed

for 10,000 people for thee months).

|

Refugees and Displaced

Communities

Health Update - A supplement to Issue no. 45 June 1991

Page Navigation

This edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online is

produced by Rehydration Project.

Dialogue on Diarrhoea was published four times a year in English,

Chinese, French, Portuguese, Spanish, Tamil, English/Urdu and Vietnamese and

reached more than a quarter of a million readers worldwide.

The

English edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea was produced and distributed by

Healthlink

Worldwide.

Healthlink Worldwide is committed to strengthening primary health care and

community-based rehabilitation in the South by maximising the use and impact

of information, providing training and resources, and actively supporting

the capacity building of partner organisations. - ISSN 0950-0235 Reproducing articles

Healthlink Worldwide encourages the reproduction of

articles in this newsletter for non-profit making and educational uses. Please

clearly credit Healthlink Worldwide as the source and, if possible, send us a copy of any

uses made of the material.

|

updated: 23 August, 2019

|

version of this Issue