|

| |

Issue no. 37 - June 1989

pdf

version of this

Issue version of this

Issue

|

There is much information in this issue that is valuable

and useful. Online readers are reminded, however, that treatment guidelines and health

care practices change over time. If you are in doubt, please refer to

WHO's up-to-date Dehydration Treatment

Plans.

|

Pages 1-8 Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online Issue 37 - June 1989

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 37 June 1989  Page 1 2

Page 1 2

Persistent diarrhoea

Most episodes of diarrhoea are acute - they start suddenly and are quite short, lasting

between two and seven days. Most are due to infections in the bowel. A proportion of acute

cases, about one in ten, become persistent, lasting more than two weeks. Their importance

is that they account for almost half of diarrhoea deaths. They also require extra

treatment in addition to the oral rehydration therapy which is so effective for most cases

of acute diarrhoea. Chronic diarrhoea, which does not start with an acute infectious

episode, may be due to a variety of metabolic or structural conditions or to parasitic

infections. Chronic diarrhoea, which can often continue for months and years, is a

different type of problem from persistent diarrhoea and is not considered in this issue.

|

Continued feeding is essential for treating both acute and

persistent diarrhoea. Clean and appropriate food A most important aspect of the management of persistent diarrhoea is appropriate diet.

This issue of DD concentrates on the linked themes of persistent diarrhoea

and dietary management. It includes a report of an important WHO meeting and an article on

the dietary management of diarrhoea.

|

Lactose intolerance Lactose or milk sugar, is the main carbohydrate source of energy for infants. Lactase,

the gut enzyme required to digest and absorb lactose, is easily damaged by infections and

malnutrition. How important is lactose intolerance, how is it diagnosed and managed? A

number of readers have asked these questions to which DD replies on="#page6">page 6. WAMC and KME

|

In this issue:

- Persistent diarrhoea and dietary management

- Lactose intolerance

- Health Basics: Breastfeeding

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 37 June 1989  1

Page 2 3 1

Page 2 3

| WHO: Meeting report and guidelines |

WHO meeting on

Persistent Diarrhoea in Developing Countries

(WHO/CDD/88.27) Children in developing countries may experience as many as ten episodes of acute

diarrhoea per year. The vast majority of these episodes can be successfully treated with

oral rehydration therapy (ORT) and continued feeding. Antibiotics should be used only for

dysentery or suspected cholera. What is less certain is what to do if the diarrhoea does

not stop. If diarrhoea lasts for more than two weeks (persistent diarrhoea) the effect

upon nutritional status may be especially serious, and the chances of death increase as

much as 20 times. Studies from various developing countries have shown that between three

and 20 per cent of episodes of acute diarrhoea become persistent, and up to one half of

all diarrhoea-associated deaths occur during episodes of persistent diarrhoea. The World Health Organization held a meeting of paediatricians, epidemiologists,

nutritionists and microbiologists to summarise current knowledge of persistent diarrhoea

and define research priorities. Although many of the studies reported were incomplete,

certain preliminary conclusions could be drawn. Risk factors

- 1. Age

Persistent diarrhoea occurred most frequently during the first year of life when, in

healthy infants, rates of growth and weight gain are most rapid.

- 2. Malnutrition

Persistent diarrhoea causes more malnutrition than acute attacks. The mean duration of

episodes of diarrhoea in malnourished infants was also longer than in adequately nourished

children.

- 3. Impaired immune defences

The risk of persistent diarrhoea was also increased by impaired immunity (as measured

by skin testing). Presumably a healthy immune system is required to fight off gut

infections. Measles and malnutrition, which can damage immunity, did not appear to be the

cause of defective immunity in these studies.

- 4. Previous diarrhoea

Children who had recently had an episode of acute diarrhoea or who had ever experienced

persistent diarrhoea were more likely to have persistent diarrhoea in future. This may be

because of damage caused to the gut by the previous episode, or some other change in the

child's defences against infection. Other infections do not predispose to persistent

diarrhoea.

- 5. Specific gut infections

Infection with certain micro-organisms (especially Shigella, enteropathogenic E

coli and, in malnourished children, cryptosporidium) appears to increase the

risk of persistent diarrhoea. Increased numbers of bacteria which normally grow in the

large intestine have been found in the small intestine of infants with persistent

diarrhoea, but it is not known whether this abnormal colonisation caused the diarrhoea to

go on longer.

Treatment Continued feeding is an essential part of the treatment of persistent diarrhoea, to

counter the impact of persistent diarrhoea on nutritional status and maintain hydration.

Persistent diarrhoea affects nutrition because of:

- decreased intake of food;

- impaired absorption of food;

- loss of nutrients from the body through the damaged lining of the intestine; and

- increased energy requirements because of fever or the need to repair intestinal damage.

Food Breastfed babies should continue to breastfeed during persistent diarrhoea. Children

with persistent diarrhoea may be intolerant of animal milk because of their inability to

digest lactose; this is most likely to be a problem when the child's diet consists

entirely of milk from animals. Decreasing the lactose content of animal milk by the

traditional method of yoghurt making may be beneficial in some patients. When this is not

effective, soy milk, which contains neither lactose nor milk proteins, can be tried. For

children above six months of age, weaning foods which are locally available, high in

energy, low in bulk, nutritious and culturally acceptable, are recommended. Alternatively,

a diet based on finely ground chicken may be tried. Vitamins such as A, folic acid and

B12, and minerals such as zinc and iron may help the repair process of the gut and boost

immune defences. Rehydration Hydration is maintained by giving extra drinks and ORS if needed. Very occasionally a

child may fail to absorb glucose and require intravenous fluid. Antimicrobials and other medicines Antibiotics are currently reserved for dysentery (diarrhoea with blood and pus in the

stools). Use an antibiotic to which most Shigella strains in the community are

sensitive. Studies are in progress to define more accurately the possible role of

antibiotics for other specific infections in persistent diarrhoea, for example in

enteropathogenic E coli infections, for which oral gentamicin may shorten the

duration of the illness. Other drugs are of no proven benefit. Research priorities

Further research is required into all the areas discussed above, but the following were

highlighted. 1. Epidemiology Community based studies are required to define the relationship of persistent diarrhoea

to age, season, infectious agents, morbidity and mortality and to define risk factors for

persistence. 2. Infection and immunity

- Does the type of micro-organism present in the small intestine or stool culture during

acute diarrhoea determine whether the illness will become prolonged?

- Is there a role for antibiotics and other drugs in the treatment of persistent

diarrhoea?

- Can the risk of persistent diarrhoea be reduced by appropriate feeding and the use of

cereal-based oral rehydration solutions, rather than standard ORS, during acute diarrhoea?

The death rate from acute diarrhoea can be cut by ORT. The next challenge is to reduce

mortality due to persistent diarrhoea. It is hoped that the recommendations and research

generated by this meeting will help to meet this challenge. A full report of the meeting

was published in the Bulletin of the World Health Organization 66: 709-717 1988. Professor David Candy, Department of Child Health, King's College Hospital, London

SE5 8RX, UK.

WHO Guidelines Nutritional management of persistent diarrhoea

There have been few studies of the dietary management of persistent diarrhoea, but

experience in the nutritional therapy of acute diarrhoea, of chronic diarrhoea of infancy

in industrialised countries, and of severe protein-energy malnutrition provides valuable

guidance. Several clinical studies have shown that continued feeding during acute

diarrhoea results in improved nutritional outcome and, in some cases, less severe

diarrhoea. Although the benefits of continued breastfeeding in persistent diarrhoea have

not been determined, it is recommended that breastfeeding be maintained during such

episodes. Weaning foods

Studies during acute diarrhoea and experience gained in the rehabilitation of severely

malnourished children show that weaning mixtures prepared from locally available foods are

generally well tolerated. These food mixtures should be energy-rich, have low viscosity,

and have low osmolality. In selecting a diet: complementary protein sources should be

used; complex carbohydrates (starches) should be used to avoid hyperosmolality and reduce

the problem of lactose maldigestion - e. g. milk-cereal mixtures are preferable to milk

given alone; and fats that are most readily digestible should be preferred, especially as

a means of increasing the energy intake. Giving small feeds more frequently during illness

may help to maximise nutrient absorption Vitamins and minerals Folate, zinc, iron, vitamin B12, vitamin A, and possibly other micro-nutrients are

involved in intestinal mucosal renewal and/or a variety of immunological responses.

Supplementary vitamins and trace elements should be given during persistent diarrhoea, if

possible. Milk from animals Animal milk should not be routinely restricted during the treatment of acute diarrhoea.

Nevertheless, in some infants with persistent diarrhoea, milk intolerance plays an

important role in prolonging diarrhoea. This occurs mostly in infants who receive animal

milk as the sole food. Reducing the amount of lactose in the diet can reduce the severity

and possibly the duration of persistent diarrhoea. Convalescent feeding Appropriate nutritional therapy during convalescence ensures that children return at

least to their pre-illness nutritional state. Studies have shown that the desired level of

energy intake (420-670J/ kg/ day) can be achieved by children who are given energy-rich

(low bulk), low viscosity diets. This level of intake can promote a rate of growth far in

excess of that expected for normal children of the same age group, thus achieving rapid

nutritional recovery. CDD Update, No. 4, March 1989, WHO, Geneva

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 37 June 1989  2

Page 3 4 2

Page 3 4

A source of faecal contamination

Baby feeding bottles are a dangerous source of diarrhoea germs. Claudio

Lanata reports from Peru. Several risk factors for diarrhoea have been identified and have been the focus of

specific interventions to reduce diarrhoeal diseases. These include contaminated water,

improper disposal of faeces, poor hygiene practices, and contaminated foods. In a recent

study of 153 children living in a poor community on the outskirts of Lima, Peru, (1)

in which we looked at the preparation and administration of weaning foods in the first

year of life, an important vehicle of faecal contamination was identified: the baby

bottle. The dangers of this must be emphasised because of the widespread use of feeding

bottles in many developing countries where diarrhoeal diseases are endemic. Contrast with cups The first clue came when microbiologic cultures were taken of foods given to children

at different times during preparation. For example, teas, which were often given,

beginning in the first month of life, had a low frequency of contamination immediately

after heating (three per cent of 87 samples) (1). If served in a cup, teas also had low

levels of contamination at the time of consumption (two per cent of 49 samples). However,

if served in baby bottles, a high frequency (31 per cent of 74 samples) were contaminated

with faecal germs, most of them with colony counts of 10,000 or more per

millilitre. When several household articles used for food were cultured, the items most frequently

contaminated with faecal coliforms were bottle nipples (37 per cent of 26 samples) and

feeding bottles (23 per cent of 26 samples) when, according to the child's mother, these

were supposed to be clean. In contrast, the mother's hands were less frequently

contaminated (14 per cent in 78 samples) and the nipples of the mother's breasts very

rarely (three per cent of 64 samples). Difficult to clean

This high level of contamination of bottle nipples and feeding bottles is most likely

due to the difficulty in cleaning them in unhygienic environments, where water is scarce

and expensive and usually contaminated, as is the case in this Peruvian community. Foods,

such as animal milk, are contaminated by the bottles which also allow the bacteria to

grow, especially if left at room temperature for more than one hour, as was documented in

this study. Recommendations

The main conclusion is that the promotion of exclusive breastfeeding during the first

four to six months of life will eliminate the feeding bottle as a source of faecal

contamination during this period. But, because breastmilk is not sufficient by itself to

satisfy the nutritional requirements of infants after this age, other foods must be

introduced while continuing breastfeeding. These foods should be given using cups or

dishes that are easier to clean and less likely than bottles to be contaminated. There is

no need to use a baby bottle. The use of baby bottles should be completely eliminated. This will not only reduce the

frequency of consumption of contaminated weaning foods, but will also help to maintain

breastfeeding, resulting in a better infant diet. Reference

1. Black, R E et al. Incidence and etiology of infantile diarrhoea and major routes

of transmission in Huascar, Peru. Am. J. Epidemiol. In press. Dr Claudio Lanata, Director General, Institute de Investigacion

Nutricional,

Apartado 55, Miraflores, Lima, Peru

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 37 June 1989  3

Page 4 5 3

Page 4 5

Appropriate dietary management

Dr Roy and Dr Haider describe

the relationship between persistent diarrhoea and malnutrition, and the types of food to

give a child who has persistent diarrhoea. Persistent diarrhoea is a syndrome in which an acute episode of diarrhoea continues for

more than 14 days. The causes of persistent diarrhoea are complicated, and relate to

previous history of illness, diet, nutritional status and immune status. Management of

cases of persistent diarrhoea may be difficult due to lack of diagnostic facilities, and

absence of well defined guidelines for treatment. Many of these children have associated

malnutrition, resulting from reduced food intake and/ or loss of nutrients through

diarrhoea. Nutrient loss may also be due to damage to the digestive system resulting from

diarrhoeal infection, or malnutrition. In a recently completed study in Bangladesh, severe

loss of nutrients was recorded in patients with persistent diarrhoea. Persistent diarrhoea and malnutrition

Since diarrhoea not only causes but also worsens malnutrition, a prolonged diarrhoeal

episode has a more damaging effect on the nutritional status of the child. Severe

deficiency of energy, protein and micronutrients often leads to kwashiorkor or marasmus in

a child who is already undernourished.

|

Management of persistent diarrhoea includes correction of

dehydration with ORT. It is known that malnourished children have more problems of digestion and absorption,

which may become worse during diarrhoea. Persistent diarrhoea is therefore a major cause

of malnutrition and subsequent death.

|

Prompt and effective intervention with an appropriate diet is a key factor in

management of persistent diarrhoea (1). Experience with persistent diarrhoea patients at

the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (ICDDR, B) treatment

centre has helped us to develop some case management procedures that may be helpful for

other countries. General management includes:

- correction of dehydration, and maintenance of hydration, with oral or intravenous

rehydration solution;

- treatment of other infections, like acute respiratory infections, urinary tract

infection, otitis media and other systemic infections which are present in many cases (2);

- observation of the volume, consistency, and frequency of stool, preferably in a

treatment centre.

A simple bedside test can be used for diagnosing carbohydrate malabsorption. If the

stool pH is less than 5.5, and stool reducing substances are more than 0.5 per cent,

carbohydrate malabsorption may be diagnosed. Choice of diet

Breastfeeding should be continued and encouraged in persistent diarrhoea patients.

Proper choice of diet requires understanding the digestive capacity during persistent

diarrhoea. Foods chosen should be easy to digest and absorb (to avoid osmotic effect),

contain adequate nutrients, and be non-allergenic, energy-rich, and acceptable to the

child. In selecting a diet: (i) complementary protein sources should be used;

(ii) complex carbohydrates (starches) should be used to avoid hyperosmolality and

reduce the problem of lactose maldigestion - e. g. milk-cereal mixtures are preferable to

milk given alone; and

(iii) fats that are most readily digestible should be preferred, especially as a means

of increasing energy intake.

|

Continued feeding prevents the malnutrition which can

result from persistent diarrhoea. Foods used should also be available, not too expensive, and culturally acceptable.

Children with persistent diarrhoea are very often anorexic and dietary management of these

children may be difficult at the beginning. This can be overcome in most cases by giving

frequent small feeds during the first few days.

|

|

In the developed countries, a wide range of commercially available prepared diets is

available, but there are only a few in developing countries (and these are usually

expensive). The reduction of usual lactose content in milk formula for children whose sole

source of protein is milk may some-times help to resolve diarrhoea. If reduction of the

lactose content in cow's milk (by providing mixtures containing milk and staple food

products, or by decreasing the lactose in animal milk - for example by traditional

fermentation) does not bring any improvement, the next step in management would be to give

a milk-free diet using soya based formula, or a cereal based diet. Recently at the

ICDDR,

B a cereal based liquid formula made with inexpensive, locally available ingredients (rice

powder, soya oil, glucose and egg protein) has been used successfully. Eighty one per cent

of patients over three months of age improved within five days. Another milk-free diet

prepared with rice-dahl (lentils) mixture has also been used successfully in India.(3)

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 37 June 1989  4

Page 5 6 4

Page 5 6

Severe cases Most children respond to this dietary regime. However a small proportion of children

with severe persistent diarrhoea (high stool volume and marked weight loss) may require

specialised treatment in hospital and further modified diets, like a comminuted (finely

chopped) chicken diet. Though it is efficient for management of severe cases, this diet is

too expensive and difficult to prepare at home for most people in developing countries. Patients who fail to respond to the reduction of the lactose content of the diet, and

cereal based or comminuted chicken diets can be given a commercially available casein

hydrolysate formula, 'Pregestimil' (Mead Johnson and Co). If there is no improvement in

diarrhoea a week after the introduction of these diets, other underlying causes of

diarrhoea should be investigated. These include small bowel bacterial overgrowth, severe

enteropathy, monosaccharide intolerance and organic disorders. Most children will respond

to specific dietary and/or antimicrobial therapy. However, some with very severe food

intolerance, will be unable to take food orally and will have to receive intravenous

alimentation for several days or weeks, before progressive amounts of readily absorbable

nutrients can be administered orally. If the diarrhoea stops with any of the above mentioned diets, continue with the same

diet for a minimum of two weeks. Subsequent follow-up at weekly intervals is necessary to

monitor growth and the gradual transition to normal foods. Vitamin A, folic acid and zinc should be given routinely as these patients are usually

deficient in these essential micronutrients. Although persistent diarrhoea is a challenging problem, when treatment is based on

appropriate nutritional therapy, the results can be very encouraging. References I. Roy, S K et al., 1989. Persistent diarrhoea: a preliminary report on clinical

features and dietary therapy in Bangladesh. J. Paediatr. 35.

2. Roy, S K et al., 1988. Persistent diarrhoea syndrome (PDS) among Bangladeshi

children. Abstracts of the XII th International Congress for Tropical Medicine and

Malaria, 1988: 212.

3. Bham, S A et al., 1983. Protracted diarrhoea and its management. Indian

Paediatr.

20 (3): 173-8. R Haider (Research Physician) and S K Roy (Associate Scientist),

International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh, GPO Box 128, Dhaka 1000,

Bangladesh

|

Composition of

diets used in persistent diarrhoea ( / Iitre )

|

| Half strength rice suji |

Half strength comminuted chicken |

| Rice powder |

30g |

Chicken, minced |

90g |

| Egg albumin |

15g |

|

|

| Oil (soya) |

20ml |

Oil (coconut, soya) |

20ml |

| Glucose |

25g |

Glucose |

30g |

| Potassium chloride |

1g |

Potassium chloride |

1g |

| Sodium chloride |

1g |

Sodium chloride |

1g |

| Magnesium chloride |

0.5g |

Magnesium chloride |

0.5g |

| Calcium chloride |

1g |

Calcium chloride |

1g |

| Water up to |

11 |

Water up to |

11 |

| |

|

|

|

| Energy |

400 kcal |

Energy |

380 kcal |

| Osmolality |

280 mosmol/ kg |

Osmolality |

218 mosmol/ kg |

|

DDOnline

Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online Issue 37 June

1989  5 Page 6 7 5 Page 6 7

Lactose intolerance

I work in a teaching hospital in Orissa, south east India, where treatment of diarrhoea

and its complications demands a large share of my time. I am concerned by the increasing

incidence of lactose intolerance, particularly in malnourished children. It is essential

to give milk to these babies to break the vicious circle of diarrhoea and malnutrition,

and using soya milk is very costly. It is very distressing that we are sometimes forced to

stop even breastmilk temporarily due to the severity of the diarrhoea. I would very much

like to know if it is possible to obtain lactase, which seems to be the ultimate solution

to this problem. Dr P Suvarna Devi, Assistant Professor, Dept of

Paediatrics, M K C G Medical

College, Berhampur 760 004, Orissa, India

Acute gastroenteritis sometimes leaves young infants with secondary

complications such as malabsorption and malnutrition. It is necessary to stress good

dietary advice so that the child does not develop malnutrition. Breastfeeding is most

important in this situation.

|

For infants with acute diarrhoea with temporary lactose

intolerance, breastfeeding should be continued. Some infants develop varying degrees of lactose malabsorption. Very few have a total

lack of lactase in the gut warranting elimination of lactose until such time as the gut

mucosa returns to normal. Some develop a moderate degree of lactase insufficiency that

requires short periods of withdrawal and gradual reintroduction of breastfeeds.

|

The majority of children will have a mild degree of insufficiency. They do well with

alternating breastfeeding with a lactose free cereal diet. The danger of permanent

discontinuation of breastfeeding should be prevented by proper education. The value of

lactose free cereal diets made of locally available grains needs no emphasis. The role of drugs in inducing lactose deficiency should be remembered before

prescribing them. There needs to be a balanced approach to dietary management during

diarrhoea. One cannot be so particular about breastfeeding in the presence of severe

lactose malabsorption. On the other hand, prescribing lactose free formulas, even for

trivial intolerance, is not warranted. It is better to use cereals and pulses as the best

supplementary foods in diarrhoea with lactose intolerance . Dr P Natarajan, Aswini Hospital, Villupuram 605 602, India

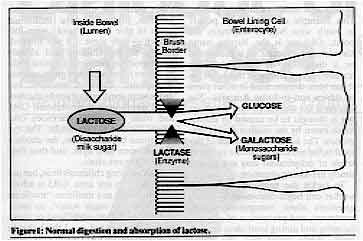

DD replies Lactose, or milk sugar, is a disaccharide carbohydrate and an important

constituent of both human and other milks. In the small bowel this is split by the enzyme lactase,

on the surface of the enterocytes, the cells lining the small bowel, into the

monosaccharide sugars, glucose and galactose (see="#Figure 1">Figure 1).

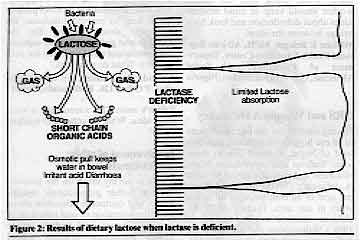

Malnutrition, bowel infections and certain drugs can damage the lining cells so that the

amount of lactase is reduced. This condition in children is called acquired or temporary

lactase deficiency. When someone with lactase deficiency has a lot of lactose sugar in

the diet, the bacteria in the bowel act on the sugar breaking it down into short chain

acids. These both irritate the bowel and limit absorption so that stools become acid and

watery (see="#Figure 2">Figure 2). This may be associated with abdominal

discomfort and extra flatus (wind). Many individuals, including most adults, and some

racial groups in particular, are lactase deficient. It almost amounts to physiological

lactase deficiency of adults. Most of them can and do tolerate some lactose as milk in the

diet.

Health workers are more conscious about lactose intolerance because of the small

proportion of diarrhoea cases where this deficiency causes problems. Also some artificial

milks contain extra added lactose and this puts stress on the sugar splitting enzyme

system. Some baby food companies are promoting lactose-free or low-lactose milk

substitutes as the answer to the question "what nourishment should I give my child

who has diarrhoea?"

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 37 June 1989  6

Page 7 8 6

Page 7 8

|

Figure 1: Normal digestion and absorption of lactose. |

|

Figure 2: Results of dietary lactose when

lactase is deficient.

|

How do you know if a baby really has lactose intolerance?

- Test the stool with a blue litmus paper which turns pink at about , pH5.5-pH6. Dip

the paper in the liquid stool and look for the colour change. The most likely cause of an

acid stool is lactose intolerance. This is a screening test rather than definite proof of

diagnosis.

- Test for reducing sugars in the stool. Use a "Benedict-test" system.

"Clinitest" is the most widely available and convenient form. Five drops of a

freshly collected liquid stool are diluted with 10 drops of water in the little test tube.

A "Clinitest" tablet is added and the mixture will heat up and froth. Check the

colour of the fluid against the chart provided. An orange-brown colour indicates >0.5

per cent of reducing substances. This is very suggestive of carbohydrate

malabsorption.

- Milk withdrawal and challenge. The two tests described above check for the presence

of lactose intolerance, but do not reveal whether it is clinically important. Many infants

with acute infectious diarrhoea have temporary lactose intolerance that is nor clinically

important. They do not require any change in diet even when the above tests are positive.

The clinical importance of lactose intolerance can best be determined by checking whether

diarrhoea rapidly worsens when milk is given, and rapidly improves when milk is

temporarily replaced by a cooked cereal or other lactose-free food. Dietary changes to

reduce the amount of lactose are only needed when lactose intolerance is clinically

important.

Managing clinically important lactose intolerance in infants

Remember that in most cases in infants the intolerance is only partial and temporary.

Once the cause is remedied, the infection has settled or the malnutrition recovered, the

new cells will make lactase again. The steps described below should be taken in sequence. Try each for two or three days.

If diarrhoea has not improved, move to the next step.

- Dilute cows' milk or formula milk to half strength. Make up the milk in the usual

way and then add an equal volume of clean drinking water. This will dilute any lactose

along with other components of milk. Give extra cereal pulse mixtures to make up the

nourishment requirements. This is not appropriate in the first four months of life (see="#Acute">letter from Dr Natarajan). (Note - pulses are leguminous vegetables,

peas, beans, dhal, gram, etc.)

- Replace milk with milk products which are modified in traditional ways, e. g. as

curds or yoghurt, and therefore have a reduced lactose content.

- Withdraw milk completely for a few days. Breastmilk should only be withdrawn as a

last resort. Ask the mother to express her milk to keep up production as her baby will

need it again in a few days time. Give cereal pulse mixtures as suggested above, or use a

soy-based milk substitute for infants below four months of age.

Note Lactase-like enzymes can be recovered from a variety of vegetable

and animal materials, e. g. yeast. However, the pure forms, suitable for converting the

lactose of milk for food, are very expensive so this is not a realistic alternative to

soya milks. (See question in letter from Dr Suvarna Devi).

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 37 June 1989  7

Page 8 7

Page 8

Students as communicators

During a recent epidemic of diarrhoea in our state the Indian Medical Association

obtained a donation of two tons of glucose, plastic packing material and printed

instructions. We organised college, high school and technical school students throughout

the state to prepare more than 800,000 small packets of ORS using a simplified formula

with glucose and sodium chloride. The students then distributed the packets house to

house, providing the product and a message on how local fluids could also be used to

prevent the dangerous dehydrating effects of diarrhoea. The project grew and was

undertaken in all major cities and rural areas of Sadvichar Parivar, a state of more than

30 million. Lions, Rotary, Jaycees and women's groups joined in as well. Students were

highly effective communicators, often mixing the solution and drinking it in public to

create confidence. Widespread community acceptance was evident and we are proud that while

many other states clamoured for cholera vaccine, our communities were effectively educated

to the use and effectiveness of ORS in diarrhoea. Dr P Mehta, Honorary Secretary, IMA College of General Practitioners, Gujarat, India

Combining beliefs

Much health communication misses its mark because health workers unquestioningly

translate health messages from English, French or other languages directly into the local

language. While the words themselves may translate, the ideas behind them often get lost,

because local cultural disease perceptions do not always relate to modern scientific

ideas. The solution is not to revert totally to local explanations of the disease process,

but to find some common ground between different medical and cultural ideas. This process

can best be achieved during discussions between the health worker and small community

groups. This example of the Yoruba people in south west Nigeria illustrates the point. Oka

ori is the Yoruba name for sunken fontanelle. It is thought to be a disease in its own

right. The Yoruba are not unique in this belief, as it has been documented in other parts

of Africa and in Latin America. The disease is not associated with diarrhoea but is

thought to be caused by certain foods eaten by the mother during pregnancy. The health

implications of this local belief are that moderate to severe levels of dehydration may

not receive timely life-saving attention. To tackle the problem, the health worker can begin discussion by asking questions about

recognition, cause, treatment, and prevention of oka ori, listening and

noting local ideas on each issue. While doing this, the health worker should keep in mind

modern ideas about dehydration and look for a bridge between the ideas. William R Brieger, MPH, African Regional Health Education Centre, Department of

Preventive and Social Medicine, University of Ibadan, Nigeria

ORS and Vitamin A Deficiency Having worked for the last three years in an eye hospital in the south east flatland of

Nepal, I would like to share some findings and experiences. Night blindness and clinical

signs of Vitamin A deficiency (VAD) are found in six per cent of all children aged up to

ten years in our area. (Survey of 70,000 children checked at their homes in 1988.)

Malnutrition and diarrhoea are the main contributing causes of VAD. In the hospital, forms

are also filled out about the history of illnesses and food habits of VAD children. Ninety per cent of the children with corneal lesions had had diarrhoea recently, or

were still suffering from diarrhoea. Most of them were seen by a doctor before they came

to us, because of illness and diarrhoea. Most were given ORS but nutritious foods like

bananas, yoghurt, papaya (traditional foods to give in diarrhoea) were forbidden - only

some rice was allowed. Nearly all the children had already developed eye problems (at

least night blindness), but were not given vitamin A capsules, although antibiotic eye

drops were sometimes given by the doctor. Parents gave their children ORS and some rice

while diarrhoea continued for one to two weeks. The eye conditions became worse, the

children did not open their eyes, and then they came to the eye clinic. ORS is saving children's lives, but not their sight, in our area. ORS is advertised in

Nepal as a medicine: 'medicine water' or 'salt-sugar water', so many people think that

other food or treatment is not needed . . . I think that in countries where VAD is still a

big problem, brief information on ORS packets could help to prevent blindness, for

example, about looking for eye changes and giving vitamin A capsules and nutritional

advice specific for each country. What do you think? Cordula Ran, Lahan, c/o United Mission, P 0 Box 126, Kathmandu, Nepal

Editor's note: This sounds like a very good idea. What do other DD readers

think?

Involvement of other professionals

I wish to air my views on the involvement of other professionals besides nurses and

doctors in education about and administration of oral rehydration therapy. These could

include public health inspectors, primary school teachers and voluntary social

organisations. The rate at which knowledge of ORT is spreading within our community is not

encouraging, hence the need for programmes to give a role to non-health personnel. Oyebo Olunyong, Primary Health Care Centre,

Ikire-Ibadan, Oyo

State, Nigeria

|

Scientific editors Dr Katherine Elliott and Dr William Cutting

Managing editor Kathy Attawell

Editorial advisory group

Professor J Assi Adou (Ivory Coast)

Professor A G Billoo (Pakistan)

Professor David Candy (UK)

Professor Richard Feachem (UK)

Dr Shanti Ghosh (India)

Dr Michael Gracey (Australia)

Dr Norbert Hirschhorn (USA)

Dr Claudio Lanata (Peru)

Professor Leonardo Mata (Costa Rica)

Dr Jon Rohde (USA)

Dr Mike Rowland (UK)

Ms E O Sullesta (Philippines)

Professor Andrew Tomkins (UK)

Dr Paul Vesin (France) With support from AID (USA), ODA (UK), UNICEF, WHO Publishing partners

BRAC (Bangladesh)

CMAI (India)

CMU (China)

Grupo CID (USA)

HLMC (Nepal)

lmajics (Pakistan)

ORANA (Senegal)

RUHSA (India)

Consultants at University Eduardo Mondlane (Mozambique)

|

Issue no. 37 June 1989

Page Navigation

This edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online is produced by Rehydration Project. Dialogue on Diarrhoea was published four times a year in English, Chinese, French, Portuguese, Spanish, Tamil,

English/Urdu and Vietnamese and reached more than a quarter of a million readers worldwide. The English edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea was produced and distributed by Healthlink Worldwide. Healthlink Worldwide is committed to strengthening primary health care and

community-based rehabilitation in the South by maximising the use and impact

of information, providing training and resources, and actively supporting

the capacity building of partner organisations. - ISSN 0950-0235 Reproducing articles

Healthlink Worldwide encourages the reproduction of

articles in this newsletter for non-profit making and educational uses. Please

clearly credit Healthlink Worldwide as the source and, if possible, send us a copy of any uses made of the material.

|

updated: 23 August, 2019

|