|

| |

Issue no. 39 - December 1989

pdf

version of this

Issue version of this

Issue

|

There is much information in this issue that is valuable

and useful. Online readers are reminded, however, that treatment guidelines and health

care practices change over time. If you are in doubt, please refer to

WHO's up-to-date Dehydration Treatment

Plans.

|

Pages 1-8 Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online Issue 39 - December

1989

|

DDOnline

Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 39 December

1989  Page 1 2

Page 1 2

What people think and do about diarrhoea

Health workers need know what believe diarrhoea and they deal it. This issue DD looks

at the significance of beliefs and behaviour, and methods of finding out what people think

and do

Good

hygiene ... |

... and sanitation are important to prevent diarrhoea.

|

Continued feeding, including breastfeeding, during

illness helps to minimise the effects of diarrhoea

|

In this issue:

- Rapid survey methods

- Diarrhoea: beliefs and behaviours

- Readers' viewpoints

|

|

DDOnline

Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 39 December

1989  1 Page 2 3 1 Page 2 3

Research methods

Findings from several studies of beliefs and practices related to diarrhoeal

disease have recently been published. P Stanley Yoder describes

one way to collect data for this type of study. Research we carried out in three language groups (Hassaniya. Fufulde. Fulani) in

Mauritania, and three language groups (Nupe, Hausa, Gwari) in Nigeria, all gave very

similar results.

|

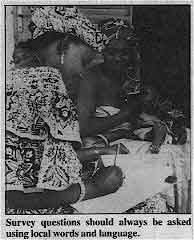

Survey questions should always he asked using local words and

language. They showed that a number of illnesses (from four to eight), whose symptoms include

loose/ frequent stools, are identified in the local language, and that these illnesses are

labelled or diagnosed according to symptoms, causes or both. Also, that diarrhoea

accompanied by what are regarded as signs of dehydration, is identified as an illness

distinct from diarrhoea and usually unrelated to other diarrhoeas. There is not a single

term that groups diarrhoeal disorders into one category of illness.

|

We used a quick and simple method to collect information about how illnesses are

classified. We also investigated how symptoms are grouped according to illness, and what

causes and options for treatment are known in different cultural groups. The method is to

interview small groups of women (from three to five m a group), asking questions in local

terms about common illnesses. The questions are always open ended and move from the

general to the specific within each session, those being interviewed providing the terms

for later questions. During the first two days, questions are mostly asked about names of

illnesses, in order to get a comprehensive list. Then questions are asked about the

causes. symptoms and possible treatments. Information collected on specific illnesses (symptoms, causes, and treatments) is

grouped into tables to make it possible to compare the answers of each group to the same

questions. This allows the researcher or health worker to evaluate the relative

consistency of the symptoms given for a particular illness as well as to decide about the

range of treatment possibilities. The main advantages of this approach are: the short amount of time required; the

informants provide all terms and categories for questioning; and the symptoms can be

grouped, according to specific illnesses, to estimate the consistency of knowledge about

them. Research can be completed in five weeks, including one week of preparation, two

weeks of field work, and two weeks of analysis and report writing. Applying the method in Zaire

In November 1988, a study was conducted in Swahili to investigate the most common

childhood illnesses in the city of Lubumbashi, Zaire. The study was to provide information

for an oral rehydration therapy promotion campaign and for developing a questionnaire on

diarrhoea and vaccinations. Diarrhoeal illnesses were therefore given high priority.

Swahili is spoken by nearly everyone in Lubumbashi. In addition to the names given to

diarrhoeal disorders in Swahili, information was needed about what symptoms were

associated with each illness characterised by diarrhoea. The study was carried out by a Zairian anthropologist and two assistants, after

spending one week in preparation. including practising interview techniques. A total of 35

groups of women were interviewed in three different parts of the city over a period of two

weeks. The average time spent with each group was 45 minutes. Once a list of common

childhood illnesses was established and further questions did not reveal new information,

the investigators concentrated on finding out the symptoms, treatments and possible causes

for each illness associated with diarrhoea. Classification of diarrhoea

People spoke of five different illnesses which generally included frequent and/or

watery stools as characteristic symptoms: maladi ya kuhara, kilonda ntumbo, lukunga,

kasumbi and buse. The symptoms, causes and treatments mentioned for each

illness were arranged in tables so that the common symptoms and the responses of each

group to the elements related to each illness could be compared. The analysis showed that maladi ya kuhara could be counted as diarrhoea, and lukunga

as diarrhoea with dehydration. The symptoms, treatments and causes described were very

different for the two illnesses. By comparing the symptoms named for each illness, we

found that, from a biomedical point of view, kilonda ntumbo can be characterised as

dysentery or amoebiasis, kasumbi as diarrhoea with nappy rash, and buse as

diarrhoea which occurs in a breastfeeding child when the mother becomes pregnant. Are

these all different kinds of diarrhoea in Swahili? A study of the data showed: first, that there is a high level of consistency in the

symptoms, causes and treatments mentioned for each illness; and second, that there are

major differences between the five illnesses in terms of symptoms, causes and treatments.

The degree to which mothers see relationships between these five illnesses is not clear,

but it is clear that they are distinct illnesses. Nevertheless, since all include loose or

frequent stools as symptoms, a survey on morbidity due to diarrhoea would need to seek

information on all five illnesses. This suggests that, if health education campaigns aim only at illnesses that are local

translations of the term 'diarrhoea', mothers will understand the messages as being

concerned only with that one illness rather than with a range of diarrhoeal disorders. P Stanley Yoder, Senior Research Director, HealthCorn Evaluations, University of

Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA.

|

|

DDOnline

Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 39 December

1989  2 Page 3 4 2 Page 3 4

Collecting information

This article outlines a series of ways to collect information about beliefs and

behaviour, known as RAP (rapid assessment procedures), applied to understanding of

diarrhoeal diseases. RAP can be used to replace surveys when resources are limited and only minimal

information can be collected quickly before, during, or after programme development. RAP

is preferably used to complement and enrich information obtained by a survey which

assesses local conditions and needs; knowledge, attitude and practices; opportunities for

intervention; and the activities and effects of different programmes. RAP is short for

Rapid Assessment Procedures, but the name was also chosen for its ability to convey some

of its characteristics. Research activities using RAP are rapid (two to four weeks of

fieldwork), community based, focused, action oriented, and low cost. Techniques

The techniques used in RAP are:

- Limited participant observation - observation of a community, household or

programme to gain important insights into everyday life and activities.

- Observation - looking at and listening to events and behaviours of interest.

- Conversation - informal individual or small group conversations.

- In depth key informant interview - more detailed interviews with a selected group

of individuals, asking open-ended questions and incorporating additional questions based

on responses.

- Survey interviews - structured or close-ended questionnaire given to a selected

group of respondents.

- Focus group - discussion in which a small group of participants (six to ten)

guided by a facilitator, talk freely and spontaneously about topics considered important.

Different community group meetings (church, women, school, co-operatives, committees,

etc.), though not focus groups in a strict sense, can also be used to obtain information.

A more complete description of each technique is provided in the RAP field guide and

other manuals. Data collection with each of these techniques is guided by checklists (for

observation, for example), discussion guides (for focus groups), interview guides, etc. We have used RAP to learn more about diarrhoeal disease in Central America and Panama

in relation to the following:

- popular and health providers' perceptions, definitions and response to diarrhoea

episodes in children

- infant and child feeding and care practices

- sanitary conditions in homes and surroundings

- existing distribution systems for medicines

- sources of information for mothers and health providers

The fieldwork activities were concentrated in three areas: in the community, the

household and among health providers. Detailed guidelines with specific questions for data

collection were developed; here we will only outline the main topics or sectors of

information included within each area and illustrate some of the findings. Community

Information about the community can be obtained from available data (census, reports,

theses etc.). Other relevant and more specific information (for example, on traditional

health providers) can be obtained during fieldwork through observation and interviews with

key informants, such as community leaders and school teachers. Household

A minimum of 15 households (for communities of 1,000 inhabitants) is selected. When

random selection is not feasible, a range of households from different locations should be

selected. Contrasting households (e. g. those with children who frequently have diarrhoea,

and with children who seldom have diarrhoea), can be selected to make the survey more

representative. Mothers of selected households are interviewed as key informants using

more structured questionnaires. Focus groups of mothers with children under five can also

meet to discuss the topics. Useful information can be obtained from these interviews and group discussions about:

family composition; socio-economic conditions; characteristics and sanitary conditions of

the home and surroundings; different types of diarrhoea - causes, symptoms, perceptions of

severity, health care seeking and treatments; detailed description of the last episode of

diarrhoea in the family and response to it: diet of healthy children and of children with

diarrhoea; child care (especially food preparation, faeces disposal and handwashing);

remedies (home and commercial medicines, including ORS) used for diarrhoea in the home;

knowledge and use of ORS; sources of information. Health care providers

These include health care providers from both biomedical (e. g. health post, clinic,

dispensary, pharmacy, store), and traditional (e. g. healer, midwife, masseuse) health

resources identified at the community level, especially those consulted in cases of

particular types of diarrhoea. Different types of health providers are key informants and

can be interviewed in groups. Additional information can also be gained by observing the

interaction between users and providers of health care. Information about health providers includes: characteristics of health resource/health

provider; types of services offered, especially for diarrhoea; knowledge and practices in

regard to diarrhoea - types, causes, symptoms, and treatments; inventory of remedies for

diarrhoea in health resource/home of health provider; knowledge and use of ORS (can

include observation of preparation of ORS packet); interaction between health provider and

user (observation of a consultation for diarrhoea); sources of information, educational

and informative materials available. Information obtained using RAP can be very valuable for programme planning,

implementation and evaluation. Consideration of techniques for data recording and

organisation, qualitative data analysis and report writing have not been dealt with here,

but are crucial to produce useful information. These are discussed in detail in the RAP

field guide.

|

|

DDOnline

Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 39 December

1989  3 Page 4 5 3 Page 4 5

Examples of health resources

in a Guatemalan community Popular medicines

- Home - herbs from bush and patio and commercial medicines

Traditional healers

- Folk curers (curandera) - four women who are also masseuses (sobadora) and one

woman who is also a clairvoyant

- Masseuses (sobadura) - four women mentioned above, two other women and two men

who are also bonesetters (hueseros)

- Spiritists - one man and one woman

- Midwives (comadrona) - four women (two of them used occasionally)

Modern non-government

- Injectionists (pone inyecciones) - four women and two men

- Stores (tienda)

- Drugstores (farmacia) - with one male and one female lay pharmacist

- Private physician - one during weekends

Modern government

- Health post - auxiliary nurse and rural health technician

|

The RAP field guide (price US$ 8.95 plus $2.00 postage) is available in either

English or Spanish from: D Alaba, UCLA Latin America Center, University of California, Los

Angeles, CA 90024-1447, USA. Reference:

Scrimshaw: S C M. and Hurtado, E. 1988. Anthropological involvement in the Central

American Diarrhoeal Disease Control Project, Soc. Sci. Med. Vol. 27(1): 97-105. Elena Hurtado, Division of Nutrition and Health, Institute of Nutrition of Central

America and Panama (INCAP), Guatemala; and Susan Scrimshaw, School of Public Health,

University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Brazil: a RAP survey

In Porto Alegre, a Brazilian city of 2.5 million people, we investigated local beliefs

about diarrhoea, and found out about liquids and weaning foods given to children. We used

the RAP technique (see="#page3">page 3) during a study period of six

weeks. Mothers' classifications of diarrhoeal diseases are complex and combine ideas from

biomedical and popular sources. The treatment of diarrhoea at home may include changes in

the diet, use of ORS, teas and drugs. These therapies are fitted to the episodes by the

causes mothers attribute to the diarrhoea. Causes include kinds and quality of food, lack

of water, 'dirty' water, commonly known infectious diseases like otitis media, teething,

'worms', inappropriate use of drugs, particular states of mind or mood, evil eye, 'loss of

fat of the intestines', and eating earth. Episodes are divided by the mothers into simple

and complicated ones, and children with complicated cases are taken to the health centre

or hospital. Use of teas

The use of teas for infants is widespread in the study area. They are introduced into

the child's diet in the first days of life, sometimes in the hospital soon after birth,

and even when the mother is breastfeeding. Teas are used for thirst, pain (colic,

earache), soothing children when they are crying, and are given between each breastfeed or

bottle feed. Teas are the main treatment used when the first symptoms of diarrhoea appear.

They are thought to be more efficient than ORS (called 'sorinho') to stop diarrhoea. Some

mothers add salt and sugar to teas. The impact of mixing ORS with teas has not been

examined but it is certainly not recommended. The use of these teas as a supplement to

breastfeeding during the first few months of life is also dangerous because dirty bottles

and utensils cause infection. Also, any supplement makes breastfeeding more difficult,

because it may decrease the number of breastfeeds, thereby reducing the production of

milk, possibly contributing to mothers stopping breastfeeding too early. On the positive

side, giving any home fluid, including teas, to children over six months of age at the

onset of diarrhoea, may be beneficial in avoiding dehydration. Diet

Behaviour related to diet shows how popular beliefs support good as well as bad

practices. For example, mothers continue breastfeeding during diarrhoeal episodes, and

perceive it as a remedy for diarrhoea. The importance of breastfeeding was also emphasised

by traditional healers. On the other hand, mothers report that they withdraw other food

during diarrhoeal episodes: either specific foods such as beans, oranges and bananas ('

heavy' foods), or sometimes all foods. Dehydration

Due to a mass media campaign in Brazil and other health education efforts, mothers

reported the term 'dehydration' and knew it to be a severe condition. However, deeper

questioning revealed that few understood that it referred to a loss of water and salts.

Mothers would often recite the campaign slogans, but did not appear to understand concepts

such as diarrhoea, dehydration and ORS. Dehydration, for example, was often confused with

malnutrition (in Portuguese 'desidratação' and 'desnutrição'). In spite of the limitations of RAP - the generality of the guides, the need to develop

new questions, the dependence on a small number of informants, and the difficulty of

analysis - the use of this technique produces a snapshot of a set of beliefs and reports

of practices that is particularly applicable for the control of diarrhoeal diseases. For

example, traditional causes and classifications of diarrhoea are extremely complicated and

continue to change, RAP also reveals the important effect these beliefs have on popular

treatments for diarrhoea. Cintia Lombardi and Carl Kendall, Department of international Health, The Johns

Hopkins School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD 21205, USA; and Cesar Victora, Departamento

de Medicina Social, Universidade Federal de Pelotas, Pelotas, RS, Brazil.

|

|

DDOnline

Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 39 December

1989  4 Page 5 6 4 Page 5 6

Why do mothers wash their hands?

Improving handwashing has been shown to reduce diarrhoeal disease. We need to

understand why, when and how people normally wash their hands, before we can change

behaviour. This article describes a study in Peru to investigate beliefs and practices in

relation to handwashing in ten shanty towns surrounding the capital city of Lima. As well as looking at handwashing behaviour, it is also important to understand the way

in which it is affected by living conditions, especially access to water supply. Most

people in the shanty towns do not have access to piped water. Water is provided by private

vendors who sell it house to house from tankers. This sales system, in addition to being

irregular, means that the water costs much more than in neighbourhoods where there is a

proper water supply. To save money, mothers in the shanty towns re-use water for different

domestic chores. For example, the same water that is used to wash vegetables is afterwards

to wash dishes, clothes or hands. Although the scarcity and cost of water influences the

way in which it is used, this study has shown that cultural beliefs related to the concept

of 'dirtiness' and the social prestige attached to cleanliness are also important in

determining how water is used. Beliefs about 'dirtiness'

There are three kinds of 'dirtiness' that may lead to handwashing:

- Perceived 'dirtiness': when the hands look, feel or smell dirty to the mother.

She washes her hands when they are visibly soiled, smell strongIy, for example of

kerosene, or when they feel sticky. This is the most common type of handwashing.

Essentially the hands are washed because they feel uncomfortable.

- Contaminating 'dirtiness': when the hands have been in contact with anything

considered dirty, such as money, garbage or adult human faeces. All of these are felt to

be vehicles of different illnesses. Although mothers report that they wash their hands on

these occasions, observation shows that this is not always the case. Baby stools are also

not considered to be dirty or contaminating.

- Social 'dirtiness': when mothers wish to improve their general physical

appearance. This type of handwashing is very common and occurs before going out, or

receiving guests at home. It is associated with aesthetic or social values.

Since many household chores involve the mother having her hands in water, she feels

that most of the time her hands are clean and that there is no necessity for additional

washing with clean water and soap. As far as she is concerned, she is 'washing' her hands

when she is cooking, and washing dishes and clothes. Consequently, most handwashing is

very superficial and is done with the water in which vegetables, dishes or clothes,

including dirty nappies, have previously been soaked or rinsed. Methods of handwashing How mothers wash their hands depends on the kind of 'dirtiness'. For perceived

dirtiness, water alone or water with detergent remaining from previous use is usually

considered adequate. For contaminating dirtiness, previously used water with detergent,

clean water and detergent, or clean water and washing soap is used. Handwashing for social

purposes is done with cosmetic soap. However, the water mothers use to wash on these

occasions has generally been previously used by the husband and /or children. Mothers

usually dry their hands on their clothes. They may also use drying-up cloths, nappies or

any reasonable clean cloths. This study has demonstrated that mothers in shanty towns of Lima understand the concept

of contaminating 'dirtiness' but that they primarily wash their hands for practical and

social reasons. In addition, hands are rarely washed with clean water and soap and they

are generally dried on the mother' s clothes. Changes in behaviour are more effectively brought about when the existing behaviour is

understood and the intervention can be designed so that it reinforces cultural beliefs and

practices. Thus, in our educational intervention to promote handwashing, the concept of

contaminating dirtiness has been emphasised with the addition of the idea that children's

faeces should also be included in this category.

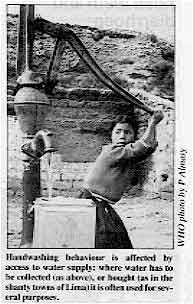

| Handwashing behaviour is affected by access to water supply: where has be

collected (as above), or bought (as in the shanty towns of Lima) it is often used for

several purposes. |

|

This study was supported by WHO and THRASHER and is part of a project aiming to

change behaviour which is related to the high incidence of diarrhoea disease. Dr Mary Fukumoto and Dr Roberto del Aguila, Instituto de Investigation Nutricional,

Apartado 18.0191, Lima 18, Peru: Dr Carl Kendall, School of Hygiene and Public Health,

Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA, Dr Duncan Pederson, IDRC, Canada.

|

|

DDOnline

Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 39 December

1989  5 Page 6 7 5 Page 6 7

Preceding articles in this issue show how important it is, for

national CDD programme planning purposes, to use qualitative research methods to obtain

accurate information about beliefs and behaviours which affect family management of

diarrhoea. The viewpoints on the following three pages may have certain scientific

limitations, either describing less formal studies or being more anecdotal reports. They

are, however, very relevant to the theme of beliefs and behaviours and provide valuable

information about particular local attitudes and actions in relation to diarrhoea.

Comments and reports from other Dialogue readers would be welcomed.

Uganda: newborns, false teeth and diarrhoea

The condition of 'false teeth', called ebiino in south western Uganda, is

believed to cause diarrhoea and fever convulsions. In fact, young neonates are given water

which is often collected from unsafe sources, and it is this contaminated water which

frequently causes diarrhoea and associated fever. The 'false teeth' belief first appeared

in the 1970s and has since spread. Dehydration, caused by diarrhoea, dries the gums,

making the canine teeth inside the gums more pronounced and pale. This is why parents and

grandparents think that diarrhoea is caused by false teeth. The response to 'false teeth' involves making a cut in the gum with unsterilised,

rudimentary instruments, to dig out the 'milk tooth', believed to be false. No form of

anaesthesia is used, and the baby's mouth may bleed for hours. This treatment is paid for

and is accepted as a panacea for, and immunisation against, childhood health complaints,

and is received by almost all children. After extraction of the teeth, some newborns also

suffer from local infections which make breastfeeding difficult and increases the chances

of malnutrition and worsening diarrhoea. Our project is trying to change beliefs and behaviour concerning 'false teeth' through

dialogue with mothers, fathers, relatives and traditional healers. Health workers explain

about the relationship between diarrhoea and dehydration and the importance of preventing

the dehydration rather than extracting the 'false teeth'. Those families who have not

removed their children's teeth but have used rehydration are encouraged to share their

positive experience during community meetings. The health workers help the parents to appreciate the fact that diarrhoea and vomiting

existed long before the false teeth problem was recognised. Emphasis is placed on sharing

information about the potential hazards of premature extraction of teeth. Water source caretakers, community based pump mechanics, and project health workers

help the parents to explore ways to prevent diarrhoea, and discuss the need to prevent

rapid death from dehydration in newborns. For those who still strongly believe in 'false teeth', the health worker recommends

instead a placebo of treating the gums with warm salty water using clean cotton wool or a

clean piece of cloth. This has been found to improve hygiene and minimise possible

infection from dirty fingers. Edward Bwengye, District Project Officer, Social Mobilisation, SW Uganda Integrated

Health and Water Project, P O Box 1216, Mbarara, Uganda.

Promoting breastfeeding in urban communities

Promoting breastfeeding is one of the most effective ways to reduce neonatal death and

illness. In some urban communities there has been significant decline in breastfeeding.

Mothers in these communities are often without family support. Deliveries take place in

overcrowded maternity wards, and after birth very little time is allowed for the mother to

be with her newborn infant. Two separate control studies of first time mothers in urban

areas in Guatemala showed that the level of support during labour affect maternal

behaviour after birth, including the bonding needed for successful breastfeeding. Early

and continues contact between the mother and her newborn infant can result in successful

and prolonged breastfeeding. Studies in Brazil (1) and Sweden (2,3) compared mothers

who had contact with their infants shortly after delivery, and for extended periods during

their hospital stay, with a control group of mothers. It was found that the mothers in the

first group were more likely to breastfeed than those in the control group. In a study in

a poor urban area of Guatemala, mothers who had had extra contact with their infants after

birth were more likely be breastfeeding one year later.(4) Efforts in urban areas should be directed towards improving maternal nutrition,

prenatal care, and especially early maternal infant contact, breastfeeding and prevention

infections. Roberto Sosa, Director, Department of Children's Hospital, 801 Sixth Street South,

St. Petersburg, FL 33701.

1. Souza, P L R, et 1974. Attachment and lactation. XIV Congreso Internacional de

Pediatria, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

2. De Chateau, P, and Wiberg, B, 1977. Long term effect on mother-infant behaviour

of extra contact during the first hour post-partum. I. First observations at 36 hours.

Acta. Paediatr. Stand. 66: 137.

3. De Chateau, P and Wiberg, B, 1977. Long term effect on mother-infant behaviour

of extra contact during the first hour post-partum. II A follow up at three months.

Acta. Paediatr. Scand. 66: 145.

4. Sosa, R, et al., 1980. The effect of a supportive companion on

perinatal problems, length of labour and mother-infant interaction. N Eng. J. Med.

303: 597

5. Sosa, R et al., 1976. The effect of early mother-infant contact on

breastfeeding, infection and growth, in Breastfeeding and the Mother. Ciba Foundation

Symposium 45 (new series) Amsterdam: Elsevier Publishing Co, pp 179-192.

|

|

DDOnline

Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 39 December

1989  6 Page 7 8 6 Page 7 8

Beliefs of rural mothers

about diarrhoea in Orissa, India

A study was carried out in a rural referral hospital to find out what mothers believe

about the causes of diarrhoea, feeding practices, treatment and ORS, in order to plan

health education activities. Mothers of children with diarrhoea attending the government

hospital in Daspalla, Orissa, were selected at random and asked about various aspects of

diarrhoea. A total of 1,000 mothers were interviewed, two thirds of whom were

non-literate. Mothers thought that diarrhoea was caused by casting of the 'evil eye' (65 per cent),

indigestion (44 per cent), 'hot' foods such as mango and egg (ten per cent), teething

(eight per cent), and food eaten by breastfeeding mothers (35 per cent). They believed

that children cannot digest the breastmilk of mothers who eat oily, spicy curries, dahl,

fish, meat, and eggs, even though most of these foods are good for lactating mothers. The

most distressing fact observed in this study was that 136 mothers, even from the more

educated group, blamed their own breastmilk for causing diarrhoea. In all these cases, one

child or more in the family had died because of previously chronic diarrhoea, and older

relatives of the mothers had attributed this to breastmilk. The incorrect ideas of mothers about the cause of diarrhoea were reflected in case

management. Cereal food and milk were restricted by 95 per cent and 46 per cent of mothers

in this study group, fearing that these would cause indigestion in children with

diarrhoea, making it worse. They preferred to give arrowroot water, sago water and barley

water. These attitudes and feeding practices will lead to malnutrition. Unfortunately a

large proportion of the more educated mothers also have wrong ideas. A quarter gave

glucose water to combat weakness, while only 11 per cent gave commercial ORS preparations. Other treatments included household remedies and homeopathy, as well as Jharphunk,a method of prayer to ward off the evil eye. Homeopathic medicine is very popular

because there are practising homeopaths in almost all villages, and the medicines are very

cheap. The people of this area are very poor and only come to hospital as a last resort

because they cannot afford allopathic medicines. The study highlights the need for a well-planned, intensive health education programme

based on these findings, to change some incorrect beliefs and to educate mothers about the

role of infection in causing diarrhoea, the importance of continued breastfeeding and of

feeding during diarrhoea, and the preparation and importance of ORS. Dr S S Mohapatra, Paediatrician, Government Hospital, At/PO Daspalla, Puri District,

Orissa 752 084, India.

Diarrhoea in Nicaragua:

causes and local remedies

Poorly stored water in cities, contaminated surface water, and bottle feeding are

important causes of diarrhoea in Nicaragua. Breastfeeding is generally regarded

positively, and women will breastfeed if possible, although this is more difficult if a

mother is working. Bottle feeding is fairly common and is not actively discouraged in

hospitals, Infant feeding bottles are widely available at low cost, which makes them

attractive to working women, although the Centre for Information and Technical Services

for Health (CISAS), a Nicaraguan NGO, tries to encourage the use of cups instead of

bottles in weaning and for giving ORT.

|

Traditional local remedies for diarrhoea and other illnesses

are being re-evaluated in Nicaragua.

Mothers sometimes believe that fear will cause illness in children, although often it

is understood that diarrhoea has links with bad food. Water is not usually seen to be

dangerous; if it is clear, mothers will think it safe to drink.

|

|

In some cases the sunken fontanelle, which is a result of dehydration. is seen as the

cause of illness, and some remedies for it include blowing smoke into the child's mouth,

holding the child upside down, or pressing upwards on the roof of the mouth. Local

remedies for diarrhoea include a drink made from cornstarch and lemon, rice water, and

teas (for example, made from guava leaves). CISAS aims to change attitudes both in the community and among health workers. Training

is needed to help health workers deal sensitively with patients who may be illiterate or

semi-literate. Resources are also limited and clinics cannot deal with the large numbers

of children with diarrhoea who could be treated effectively at home if families knew what

to do. Education of families about hygiene and health is also very important.

Based on an interview with Ana Quiros, Centro de Information y Servicios de Asesoria

en Salud, Apto 3267, Managua, Nicaragua.

|

|

DDOnline

Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 39 December

1989  7 Page 8 7 Page 8

Beliefs and behaviour:

the Maasai in Kenya and Tanzania

Success in preventing diarrhoeal illness does not depend only on providing information.

There are important lessons to be learnt by studying how communities understand diarrhoea,

the believed causes of infection, and treatments and behaviour. If sanitation, hygiene and

other practices relating to diarrhoea are to be improved, change must come from within the

community. In northern Tanzania and southern Kenya, our health team studied the beliefs about

diarrhoea of several groups of nomadic Maasai, including causes and treatment. The study

(among 231 mothers in Kenya and Tanzania) found that there were 21 believed causes of

diarrhoea. Those mentioned most were stale food, dirty water, flies, badly cooked meat,

malnutrition, and water holes used by domestic and wild animals. The study identified 29

different terms used for diarrhoea, depending on stool colour, composition and type.

Thirty two treatments for diarrhoea, mainly medicinal plants, were found as well as a

distrust of modern medicines, and a belief among some nomads that people have two

stomachs. The Maasai believe that bad food and bad water is processed by the second

stomach by washing the badness from the body. Animal fat is a popular treatment, as is the

drinking of clean water and breastmilk (for infants).

|

If sanitation, hygiene and other

practices relating to diarrhoea are to he improved, change must come from within the

community.

The Maasai showed knowledge of common causes of diarrhoea on which Maasai health

workers can build an education programme, adapting and using positive beliefs. We are now

also studying the efficiency and effectiveness of traditional Maasai treatments for

diarrhoea.

|

|

The success of Interventions relating to practical hygiene is due to the fact that many

of our own community health workers are Maasai and Samburu warriors who are part of the

community and who have combined what they see as 'modernism' with traditional practices. There is an important place for building on cultural perceptions and ideas and those

beliefs are essential in building and designing any community health initiative. As one of

our health workers said: 'At the end of the day, a mother will listen to her mother's

advice rather than to a stranger's. She'll draw on her experience from her world, not from

ideas given her in another language.' Should any DD readers wish for information about our research methods, or

for more details of our ongoing research, we would be glad to share this. Ultimately,

ethnomedical research is about listening carefully and learning before trying to teach.

The more we listened in our research, the more we realised we had to learn. Michael Meegan, Director, ICROSS Rural Health Programme, PO Box 15619, Mbagathi,

Kenya.

|

Clarification Feeding bottles: a source of faecal contamination - an article published in="dd37.htm">DD issue 37, should have credited Dr Guillermo Lopez de Romana

as co-author. The Editor would like to apologise for this omission. The authors would also

like to clarify a point made in the article by the DD editors: 'There is no need to

use a baby bottle. The use of baby bottles should be completely eliminated. This would not

only reduce the frequency of consumption of contaminated weaning foods, but will also help

to maintain breastfeeding, resulting in a better infant diet.' The authors suggest

that the recommendation to eliminate feeding bottles completely is often impractical in

cities such as Lima, because many mothers have to be away from their children for

some hours and the caretaker feeding the child, even with breastmilk, may have to use a

feeding bottle. If it is not possible to eliminate the use of feeding bottles, then

promotion of better and more hygienic use is necessary (or use of a cup and spoon).

|

Scientific editors Dr Katherine Elliott and Dr William Cutting

Managing editor Kathy Attawell

Editorial advisory group

Professor J Assi Adou (Ivory Coast)

Professor A G Billoo (Pakistan)

Professor David Candy (UK)

Professor Richard Feachem (UK)

Dr Shanti Ghosh (India)

Dr Michael Gracey (Australia)

Dr Norbert Hirschhorn (USA)

Dr Claudio Lanata (Peru)

Professor Leonardo Mata (Costa Rica)

Dr Jon Rohde (USA)

Dr Mike Rowland (UK)

Ms E O Sullesta (Philippines)

Professor Andrew Tomkins (UK)

Dr Paul Vesin (France) With support from AID (USA), ODA (UK), UNICEF, WHO Publishing partners

BRAC (Bangladesh)

CMAI (India)

CMU (China)

Grupo CID (USA)

HLMC (Nepal)

lmajics (Pakistan)

ORANA (Senegal)

RUHSA (India)

Consultants at University Eduardo Mondlane (Mozambique)

|

Issue no. 39 December 1989

Page Navigation

This edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online is produced by Rehydration Project. Dialogue on Diarrhoea was published four times a year in English, Chinese, French, Portuguese, Spanish, Tamil,

English/Urdu and Vietnamese and reached more than a quarter of a million readers worldwide. The English edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea was produced and distributed by Healthlink Worldwide. Healthlink Worldwide is committed to strengthening primary health care and

community-based rehabilitation in the South by maximising the use and impact

of information, providing training and resources, and actively supporting

the capacity building of partner organisations. - ISSN 0950-0235 Reproducing articles

Healthlink Worldwide encourages the reproduction of

articles in this newsletter for non-profit making and educational uses. Please

clearly credit Healthlink Worldwide as the source and, if possible, send us a copy of any uses made of the material.

|

updated: 23 August, 2019

updated: 23 August, 2019

|