|

| |

Issue no. 47 - December 1991

pdf

version of this

Issue version of this

Issue

|

There is much information in this issue that is valuable

and useful. Online readers are reminded, however, that treatment guidelines and health

care practices change over time. If you are in doubt, please refer to

WHO's up-to-date Dehydration Treatment

Plans.

|

Pages 1-8 Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online Issue 47 - December

1991

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 47 December

1991  Page 1 2

Page 1 2

Ask, listen... but don't forget to look

|

Health workers must ask the right

questions, and listen to what people say. But they must also look

at what people do. Helping families to make their homes safer is an important part of the prevention and

control of diarrhoea1ldisease. This issue of DD looks at questions

which relate to hygiene behaviour: how people handle food, water and wastes - human and

animal excreta, and garbage of all kinds. Faecal-oral transmission of diarrhoea germs is

the polite way to describe tiny amounts of shit somehow getting into human mouths. This

danger has to be reduced. Better sanitation and cleaner water supply can help but. to make

a real difference. families also need access to appropriate hygiene education.

|

Real understanding To be effective, this education must be based on genuine understanding of how people

think about hygiene in their daily lives and why they do as they do. Suggested changes

must fit the local environment, which should include religious and cultural traditions as

well as household and economic circumstances. Aspects of looking at hygiene behaviour are

discussed on pages 2, 3 and 4. and pages 5 and 6 show how some particularly difficult

environmental conditions are linked with persistent diarrhoea due to worms. See what people do Ansvvers to questions from readers about ORT on="#page7">page 7 also show

the importance of understanding what people do and why. This means asking questions and

listening to what people say. But, because the asking of a question can influence the

answer, it is equally vital always to look at what people actually do. We have to have the

whole picture if we hope to improve behaviour.

|

In this issue:

- Finding out about hygiene behaviour

- Worms and child health

- Problems with ORT? Your questions answered

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 47 December

1991  1 Page 2 3 1 Page 2 3

| Diarrhoea and hygiene behaviour |

Learning about what people do and why

DD explains why it is important to understand hygiene behaviour and

how this knowledge can help to reduce the spread of diarrhoeal infections. How people carry out day-to-day personal and domestic activities that relate to the

transmission of infections, including diarrhoea, is called 'hygiene behaviour'. Hygiene

behaviour is important because it affects the household level of contamination by germs,

and the extent to which those germs can infect the family. Diarrhoea-causing germs are

most commonly spread from person to person by the faecal-oral route. Hygiene behaviours

that influence diarrhoea transmission by this route include:

- where people defecate;

- whether and how hands are washed (or otherwise cleaned) after defecating. and before

preparing and eating food;

- how babies' faeces are disposed of;

- how water is stored and used; and

- how food is prepared and stored.

Why do we need to know about hygiene behaviour? People are likely to have fewer diarrhoea infections if they have access to clean

drinking water and good sanitation facilities. But, if hygiene behaviour is poor, the

health benefits resulting from provision of improved sanitation and water supplies will be

limited. Clean drinking water and better sanitation typically reduce diarrhoea incidence

by only 25 per cent (1). Interrupting faecal-oral transmission of germs

also depends on improving personal and domestic hygiene behaviours. Diarrhoeal disease control programmes have tried to improve hygiene behaviour by

introducing different interventions such as educating families about the importance of

domestic hygiene. Promoting improved hygiene has been shown to halve the number of

diarrhoea infections. But if these interventions fail, it is often because they have not

been appropriately designed or put into practice. This can be due to lack of understanding

about what people think about hygiene and why they behave in a particular way. Sometimes

it is also because the interventions have not been aimed at the behaviours which are most

responsible for spreading infections. It is therefore important to understand people's existing hygiene behaviour, and the

factors that determine it, so that health education interventions to change behaviour are

appropriate, and so that behaviour does change, leading to improvements in health.

Programmes also need to be aware that although people may know about the safest

practices, certain constraints may prevent them from actually doing things the

safest way. In Zimbabwe, Pauline Gwatirisa investigated why providing water and

sanitation had failed to reduce diarrhoeal and worm infections in poor rural communities.

Studying behaviour showed that, even when latrines were provided, defecation practices did

not always change. It was found that, although people agreed that their household toilet

was the safest place for excreta disposal, where their food gardens were several

kilometres distant from their homes, people pointed out that they would waste much time

and energy walking back home to use the toilet. They were therefore encouraged to bury

their faeces, or dig a small pit for faeces disposal near the gardens.

|

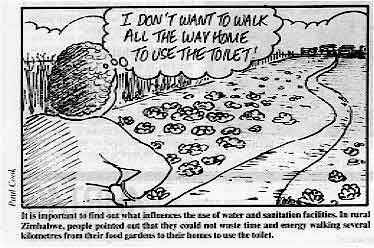

It is important to find out what influences the use of

water and sanitation facilities. In rural Zimbabwe, people pointed out that they could not

waste time and energy walking several kilometres from their food gardens to their homes to

use the toilet.

|

Most people in a community will have similar ways of doing things, but there will be

variations between families or individuals. Some ways of doing things are more likely to

increase infection spread than others, and may therefore be related to a higher rate of

diarrhoea infections. Studies help to find out which ways of behaving are most likely to

be linked to high rates of diarrhoea. Hygiene behaviour studies carried out before introducing

interventions can reveal:

- what people think and do about hygiene, and why they act in a particular way;

- the practices responsible for transmitting infection which the programme or intervention

should aim to change;

- which factors influence or limit the extent to which behaviour can be changed (such as

beliefs about cleanliness).

Similar studies after an intervention has been introduced also provide useful

information which helps to:

- monitor how well hygiene behaviour interventions are working;

- examine how water and sanitation programmes affect health and hygiene behaviour;

- identify the reasons why a programme might not be having an impact on the incidence of

diarrhoea.

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 47 December

1991  2 Page 3 4 2 Page 3 4

| Diarrhoea and hygiene behaviour |

How is hygiene behaviour studied? Hygiene behaviour studies should collect information from a large number of families if

the results are to be useful for programme planners. This is because it is important to

know that a significant proportion of people in the community behave in a particular way,

in order to design an appropriate intervention for the whole community, or to find out if

an intervention has been effective.

|

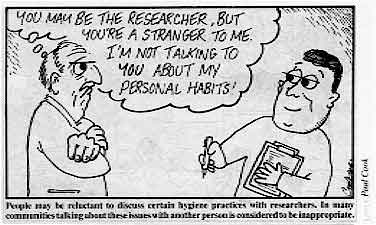

People may be reluctant to discuss certain hygiene practices

with researchers. In many communities talking about these issues with another person is

considered to be inappropriate.

Finding out what large numbers of people believe and do, and why they do it, is not

easy. Investigating how this information relates to disease is even harder. Behaviour is

much more difficult to study than whether water supplies are available. Behaviour is

difficult to define, often very variable and determined by cultural context. Identifying

'poor' behaviour can mean that people themselves are blamed for their ill

health.

|

|

Researchers have developed various methods and practical techniques for collecting

information and to help them to identify and measure the behaviours that influence the

spread of infections, including diarrhoea. The field workers who carry out the study in

the community need training in how to use the techniques. It is helpful to start by

finding out more about the social and cultural background of the community, for example

family income and level of maternal education. Preliminary studies Preliminary studies, usually on a small scale, provide information for designing a

larger study. Such preliminary studies can ensure that a questionnaire uses the right

words to refer to behaviours common in the community. One technique used in these studies

is the focus group discussion, where, for example, small groups of women are encouraged to

discuss what they think and do about child health and hygiene practices, and give reasons

for why they do certain things.

|

Designing health education messages This study shows how information about hygiene behaviour was used to design effective

educational messages. Researchers in Bangladesh wanted to develop health education

messages to improve hygiene behaviour and reduce diarrhoea infections in children living

in poor areas of the capital city, Dhaka. Through comparing hygiene behaviour in two

different groups of families, the study identified which hygiene related practices were

most likely to be associated with high rates of diarrhoea infection. Using this

information the researchers designed appropriate health education messages aimed at

improving these practices. Diarrhoea incidence in children was recorded by asking mothers to mark episodes of

diarrhoea on special calendars designed for non-literate adults. Two groups of about 50

families with children under five were selected: one consisted of households in which the

children had the highest number of diarrhoea infections, and the other of those in which

incidence was lowest. Hygiene behaviour in both groups was studied to find out if there were things which

people did differently in each group and which might increase infection spread. In the

households in which there was a higher incidence of diarrhoea infections, the researchers

observed that:

- more mothers did not wash their hands before preparing food;

- infants were more likely to defecate in the family living area, and their faeces were

more likely to be found in this area;

- families were more likely to leave household waste uncovered in the living area, and

children were observed to put garbage in their mouths more often.

Simple health education messages focusing on these three behaviours were designed to

emphasise the need to:

- wash hands before food preparation:

- encourage children to defecate away from the house at a special site, or in a latrine;

- dispose of garbage and infant faeces safely.

A later study showed that these interventions succeeded in changing the three

behaviours and in reducing the number of diarrhoea episodes, particularly among two and

three year olds.

Clemens J D and Stanton B. 1987. An educational intervention for altering water-

sanitation behaviours to reduce childhood diarrhoea in urban Bangladesh. Am. J.

Epid. vol. 125: 284-301.

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 47 December

1991  3 Page 4 5 3 Page 4 5

| Diarrhoea and hygiene behaviour |

Interviews, questionnaires and surveys Surveys are a useful way to find out what water and sanitation facilities are available

for domestic use. These methods can also be used to explore accepted norms of behaviour,

that is, what most people think they should be doing. People may say they do one

thing, but actually behave differently. They will also only answer the questions they are

asked, so questions have to be well chosen, using information from preliminary studies. Vijay Kochar describes what happened during his research in West Bengal, in India: 'Wewere studying hookworm transmission in a village with no sanitation facilities. When

interviewed, villagers confirmed our expectations, saying that people have special places

for open air defecation, which are used only for that purpose. However, when I examined

the actual stool distribution around the village, I found it to be much more varied than

had been indicated in interviews, and saw that people use the defecation grounds for other

activities too, such as collecting wood.' Cultural factors can be a major obstacle to obtaining information. In Zimbabwe, researchers

found that it was difficult to collect data on the usage of sanitary facilities by older

people - in many communities it is not culturally appropriate to discuss such issues with

another person. It is not always necessary to question people about what they actually do. Sometimes

discovering what they think about hygiene can be useful in itself. One example of this is

a study in Papua New Guinea which was designed to find out what mothers believed

about the role of babies' faeces in spreading infection. not how they actually disposed of

infant faeces (2). Field workers completed a questionnaire during open discussions with mothers. The

information was then compared with the number of diarrhoea infections in their children

over a year. Children whose mothers believed that infant faeces were not a source of

infection were more likely to have had diarrhoea. This finding helped planners to design

an appropriate educational intervention for women about the infectiousness of babies'

faeces, and the need to dispose of them safely. Direct observation Direct observation enables researchers to compare people's hygiene behaviour in their

own homes with what they say they do. Seeing what people actually do, for example, about

storing and using water, can reveal hygiene practices that could increase the spread of

infection. In a study on water use in Bangladesh, in an area where most families had access

to clean water from handpumps, people were asked where they obtained their drinking water

(3). Although most said that they drank only handpump water, close

observation revealed that some people used contaminated pond water for many other

household purposes such as cleaning feeding bottles, and that the two sorts of water were

usually stored side by side in the home. This increased the risk of transmission of

infection from contaminated water. Direct observation is, however, a labour intensive method. In addition, people may

change their normal way of doing things when a researcher - usually a stranger to the

family - is present. Jane Baltazar comments on carrying out such a study in a poor community in Metro Manila

in the Philippines: 'We designed an "observation checklist". which

included sections for the observers to record practices related to young child defecation,

and maternal water handling and food preparation behaviour. However. we encountered a

major problem.

|

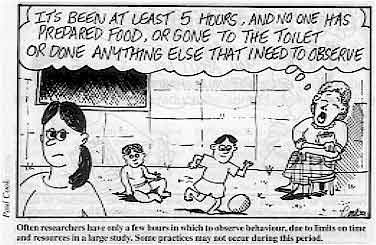

Often researchers have only a few hours in which to observe

behaviour, due to limits on time and resources in a large study. Some practices may not

occur during this period. Due to limits on time and resources. we could only spend one hour in each household.

|

Often the events we wanted to observe, like infant defecation or rubbish disposal, did

not occur during this time. Even when the interview was extended to five hours, these

behaviours were recorded in only 10 per cent of the households. Indirect observation Sometimes researchers do not have to observe how something is done. Instead they look

for and see signs that indicate that a person has done something in a certain way. For

example, a clean yard can mean that infant faeces have been swept up and disposed of

safely. These signs can be useful measures of behaviour and are easily observable even

during short interviews. Special arrangements should not be made for visits, since if

people are expecting a researcher to come to their homes they may change how they normally

do something. Conclusion The International Reference Centre for Community Water Supply and Sanitation (in The

Netherlands) is using the experience of a number of hygiene behaviour studies to draw up

guidelines to help programme planners to design cost effective and useful studies,

particularly in relation to water and sanitation programmes. These studies will enable

planners to introduce and monitor hygiene behaviour interventions that will best reduce

transmission of infection in their community. The guidelines will be published by the International Development Research Center in

1992. (Details will be included in a future issue of DD). DD would like to thank the following for permission to use papers presented

at the Workshop on Measurement of Hy giene Behaviour, held in Oxford, UK, in April 1991:

Dr Sandy Cairncross, Dr Jane Baltazar, Dr Pauline Gwatirisa, Dr Patricia Haggarty and

Professor Vijay Kochar. 1. Esrey S et al, 1985. Interventions for the control of diarrhoeal

diseases among young children: improving water supplies and excreta disposal

facilities. WHO Bulletin. vol 63:757-772.

2. Bukenya et al, 1990 The relationship of mothers' perception of

babies' faeces and other factors to childhood diarrhoea in an urban settlement of Papua

New Guinea. Ann. Trop. Paed. vol 10: 185-189

3. Zeitlyn S and Islam F, 1991. The use of soap and water in

two Bangladeshi cornmrnities: implications for the transmission of diarrhoea.

(Forthcomintg publication)

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 47 December

1991  4 Page 5 6 4 Page 5 6

Water and sanitation are not enough

Chris Smith discusses why worms, often associated with

diarrhoea, are still a major problem for young children in Palestinian refugee camps,

despite widespread access to piped water and sanitation facilities. The Gaza Strip has a population of approximately 700,000 Palestinians living on a

narrow strip of land about 25 miles long and 5 miles wide. The area is part of the

Occupied Territories, and lies on the east coast of the Mediterranean Sea, bordering Egypt

to the south and Israel to the east. Most people are refugees, with over half living in

seven camps administered by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency. The vast majority of people living in the refugee camps have access to both a piped

water supply with a tap in their house or yard (98 per cent) and some kind of latrine (97

per cent). However, infestations by roundworm (Ascaris lumbricoides) and whipworm (Trichuris

trichuria) are endemic (the latter having a known association with persistent

diarrhoea). In 1988 a study was carried out to try to find out why these infestations are

so common in spite of high levels of access to water and sanitation. To start with, stool samples were collected from young children coming to the clinics

in the camps. Tests on the samples showed that in all the camps up to half the children

treated had worm infestations. Following this initial sampling, a community based survey

was carried out in one of the camps (Beach Camp), in which infection levels were measured

in children aged under 10 years. Of 137 children tested, 10 per cent had roundworm and 26

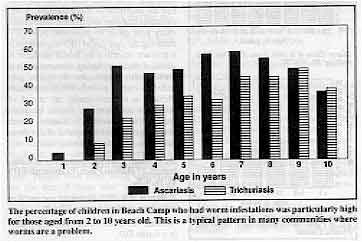

per cent had whipworm, showing a typical age prevalence pattern (see table).

|

The percentage of children in Beach Camp who had worm

infestations was particuiarly high for those aged from 2 to 10 years old. This is a

typical pattern in many communities where worms are a problem. |

Seventy-four sand samples from the camp were analysed for the presence of helminth ova

(eggs), 23 from sandy courtyards and 51 from the street; 61 per cent of the yard samples

and 75 per cent of the street samples contained Ascaris lurnbricoides ova,

although none contained Trichuris trichuria.

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 47 December

1991  5 Page 6 7 5 Page 6 7

Continued from previous page Investigating the problem

Environmental conditions and hygiene behaviour were analysed to find out why so many

children still had worm infestations: household questionnaires included sections on house

and street environments, hygiene related knouledge and attitudes, and hygiene practices of

children. Some households were selected for observation of hygiene related behaviour. The

results suggested that the persistence of worm infections was due to a combination of:

- Inadequate sanitation

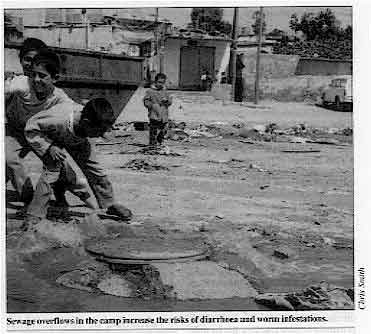

Almost every house in the camp had a latrine, in some areas

connected to a pit. While some pits were linked to a newly installed underground piped

sewerage system, others overflowed into the street.These pit overflows provided a regular source of pollution and a suitable damp

environment for helminth ova to survive (until they contaminated food, water or people's

hands and were swallowed).

|

Sewage overflows in the camp increase the risks of diarrhoea and worm

infestations.

- Seasonal flooding

In winter during heavy rains, local flooding washed the faecal contents from latrine pits

to the street surface. Piped sewers flooded the streets during these rainstorms, spreading

faecal materials throughout the camp.

|

|

- Poor disposal of faeces

During observation, researchers saw that the faeces of young children were being deposited

in household yards, either through direct defecation or through leakage from nappies.

Traces of human faeces were observed in 10 per cent of the houses during the survey.

Faecal remains were eventually swept or washed away - usually into the street.

Prevention and treatment The overflow problem can be solved by the installation of piped sewerage networks in

the camps, while health education can help to improve hygiene practices. But the problem

of winter flooding will be more difficult to solve in the near future. Without a storm

drainage system, the sewers will continue to flood the street surface. While infestations persist, proper treatment of infected children can reduce the

harmful effects of these parasites. The study suggests that, at present, although

treatment of children with anti-worm medicine is common, children who had been recently

treated did not have a significantly lower prevalence of either infestation compared with

children who had never been treated. This was true regardless of sex, age, education of

parents and occupation of father. The most likely explanation for this is that medicine is

being used incorrectly - for example, the practice of sharing out bottles of anti-worm

medicine among children in a family is known to be common. This finding highlights the need for community education about the proper use of

available drugs and medicines. The option of organising general or targeted treatment

should also be considered. Chris Smith, Project Officer, UNICEF (West Bank and Gaza Strip), PO Box 141,

Shu'fat, East Jerusalem, Israel. This study was conducted by Birzeit Community Health Unit in co-operation with the

Gaza Red Crescent Society and the UN Relief and Works Agency. Comment

Should helminth infections be controlled by mass medication? William

Cutting offers one viewpoint. The germs that cause diarrhoea and the worms that are sometimes passed in stools both

live in the human gut. These infections are transmitted from the stools to the mouth - the

faecal-oral route. The most important preventive measures for both are therefore

improvements in water supply, sanitation and hygiene behaviour. Two of the parasites, Trichuris

trichuria and Strongyloides stercoralis. can cause watery, mucoid and even

bloody diarrhoea when infestations are heavy. Apart from these features, the infections are different in almost every way. Worms are

directly responsible for very few deaths, compared with the number caused by diarrhoea.

Mortality from roundworms (ascaris) may be 1 in 100,000 children infected, perhaps 13,000

in the world each year. Acute diarrhoea infections still kill almost 4 million children

each year, and have severe effects on the growth and development of many millions more.

|

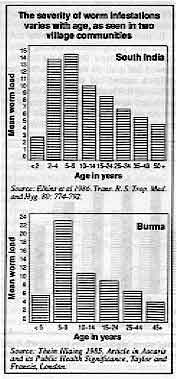

The severity of worm infestations varies with age, as seen in

two village communities

Sources:

Elkins et al 1986. Trans. R. S. Trop. Med and Hyg. 80: 774.792.

Thein Hlaing 1985. Article in Ascaris and its Public Health Significance, Taylor

and Francis, London.

Worm infestations are endemic in developing countries, mostly in children aged from

five to ten years (see table). However, levels of infestation vary enormously from place

to place. High levels are associated with poverty, poor sanitation and poor hygiene

practices.

|

Some major health agencies have recently focused on developing medication programmes

for controlling helminth parasite infections (1). They believe that with

three antiparasitic drugs (albendazole, praziquantel and ivermectin) it would be possible

to give mass treatment for most of the major human helminth infections. This treatment,

given once every year, could be combined with giving key nutrients, vitamin A in

particular. Doing this through the school system would reduce the costs to about $1 per

child per year, and it is believed that this approach would reduce malnutrition, ill

health, and the number of deaths: and improve growth, development and even intellectual

performance. Best use of resources Any campaign would thus be directed at school age children. However, in most developing

countries it is pre-school children who suffer most ill health. Among older children, it

is usually those who are not attending school who are in greatest need. This type of approach would have some serious consequences. Money spent on such a

programme might detract from investing resources in the development and strengthening of

primary health care systems and even basic health care services like the provision of

water supplies. WHO estimates that over two million child deaths every year could be

prevented by ORT - ensuring the right use of ORT has to remain a primary objective for

health services. A decision about including deworming in a child health programme should

be preceded by careful surveys to find out which children in the community are at risk of

infection, and therefore should be given medication. Preventive measures, which also help

to control the spread of diarrhoea infections, need to be given priority. Dr William Cutting, University of Edinburgh, 17 Hatton Place, Edinburgh EH9 1UW, UK.

1. Warren, KS. 1991. Helminths and health of school age children,

Lancet. 338: 686-7. Another viewpoint on this issue will follow in a future DD.

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 47 December

1991  6 Page 7 8 6 Page 7 8

| Questions and answers about ORT |

A child refusing to drink? Oral rehydration therapy may be easier in theory than in practice. What can be done in

the case of a child with dehydration from diarrhoea who cannot be persuaded to take ORS

solution, and where there are no facilities for IV treatment? Alhaji A B Amadu, The Zonal Health Management Committee Office, Lokoja General

Hospital, Lokoja, Nigeria.

Children with definite signs of dehydration are usually thirsty; they almost never

refuse to take ORS solution. The two most common explanations for refusal to take ORS

solution are (i) the child is not really dehydrated or

(ii) the child is too weak or lethargic to take the solution, as may occur when

dehydration is severe. In a few instances the cause is severe dehydration, and rehydration should be by the

intravenous route or, if this is not possible, by giving ORS through a nasogastric tube. Giving ORS solution takes patience and time, especially if a child is weak or drowsy. A

child is more likely to be persuaded to accept ORS solution from his or her mother, or

someone else known and trusted. Older children, who do not have signs of dehydration, may

refuse the solution because they do not like the taste. For such children, try adding a

little fruit juice, or give the ORS solution alternately with plain water or with another

familiar fluid that the child is more willing to drink.

Correct recipe for SSS? In my area there is some disagreement over how to make sugar-salt solution

(SSS) for

rehydration. Some doctors say that the recipe we promote (one pinch of salt to four

pinches of sugar) is wrong. This confuses health workers. Can DD help? Fr Emmanuel, Operation Health 2000, 32 College Road,

Nungambakkam, Madras 600 006,

India.

Teaching people how to measure out the correct amounts of salt and sugar to make home

made solutions is often a problem. The amount of sugar or salt in a finger pinch can vary

considerably, according to the individual's hand size and their judgement. People have

tried using teaspoons, but the size of these also varies. Some programmes have promoted

other standard-sized and locally available measuring devices (such as special plastic

spoons or fizzy drink bottle tops).

Studies show that people are more likely to make a solution that is more rather than

less concentrated than recommended. Solutions containing too much sugar and/or salt can be

dangerous, and may even increase the diarrhoea.

A child in danger of dehydration needs to be given fluids. It is better to give a child

as much as they will drink of a less concentrated solution than risk giving them too much

of one that may be dangerous.

Because of these problems, WHO now recommends the following quantities of salt and

sugar for home made SSS:

- 3g (half a level teaspoon) of salt and

- 18g (four level teaspoons) of sugar

- dissolved in one litre of clean drinking water.

WHO does not encourage the use of linger pinches or hand scoops to measure salt and

sugar for the reasons given above. The recipe used in Madras appears to provide too little

sugar, as one pinch (using the thumb and two fingers) equals about 0.5g of salt or sugar.

Thus, four pinches would provide only about 2g of sugar (per litre of water).

Alternatives to packets? Diarrhoea is a major problem in our area. We use ORS packets from UNICEF. But we have

not been able to teach people how to make their own oral rehydration solution because

sugar is not available locally. Salt can sometimes be found in a market which is four

hours' walk from us. People do have honey available. Can honey be used instead of sugar to make a home

solution for ORT? Are there any leaves that have enough natural sodium content that they

could be dried, crushed and added to the drink? Sharon Smith, Nurse Practitioner, Box 127, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

There are no widely used 'natural' substitutes for salt. Honey can be used as a substitute for glucose or sugar as 30 to 40 per cent of honey is

glucose. About 50ml of honey to a litre of water will provide the required amount of

glucose for a home solution. Cereal flour (such as rice, wheat, millet, sorghum or maize) can also be used instead

of sugar to make a home made solution. Cereals contain carbohydrates which are converted

into glucose in the intestine. Make this solution by adding two handfuls of flour to a litre of water. Boil, stirring

constantly, until the first bubbles appear (usually about five minutes), and then remove

from the heat. The solution should not be too thick to drink. After the mixture has

cooled, add two three-finger pinches of salt. If it is not possible to get ORS packets or to make home solutions with salt and sugar

or sugar substitutes, giving other types of fluids readily available in the home helps to

prevent dehydration. As well as plain water, these include vegetable and pulse based soups

and cooked cereal porridge.

Different formulations? Many families, especially in rural areas, do not think SSS and ORS solutions are

appropriate treatment for diarrhoea, as they believe that tablets, capsules and syrups are

the only 'real' treatment for illnesses. I suggest that WHO and other organisations should consider developing ORS in tablet or

syrup form, or making pills of the correct amount of sugar and salt which can be dissolved

in a specific amount of water, so that people are more convinced of their effectiveness.

What is your opinion about this'?

Bulama Abatcha, General Hospital Monguno, Monguno Local Government, Borno State,

Nigeria.

Medicines are usually bought, and given, in small quantities after a child has been

sick for a few days. If ORS is perceived as a medicine, to be bought in tablet form, there

is a danger that people will not give a child sufficient solution soon enough after

diarrhoea starts to prevent dehydration. Tablets and other formulations may also be more

expensive to produce, and therefore to buy, than ORS packets. It is important to teach people about the value of giving extra fluids, as well as

ORS solution and SSS, at home as soon as a child has passed the first loose stools. in

order to prevent dehydration. Oral rehydration therapy, in all its forms, enables families to take care of children

with diarrhoea themselves, without having to spend money on expensive drugs. However, ORS tablets (one tablet for 120ml, about one glassful, of water) are

commercially available. The product has been registered in many countries of Africa. Asia,

Central and Latin America and in the Middle East. For information contact: PATH (Program

for Appropriate Technology for Health), 1 Nickerson St., Seattle, Washington, 98109-1699,

USA.

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 47 December

1991  7 Page 8 7 Page 8

ORT success in the Soviet Union ORT was first promoted widely in the Soviet Union for treating adults during cholera

outbreaks in Astrakhan (a region in southern Russia) in the early 1970s. But. until 1985,

the standard treatment for childhood diarrhoea was an intravenous drip. Doctors advised

withholding food to 'rest the bowel' and often prescribed antibiotics. Since 1985 the

Institute of Epidemiology, together with the health authorities, has set up ORT units in

city hospitals and local children's clinics, in rural hospitals and health facilities, and

they have also promoted home treatment. Health workers at different levels are being

trained, and TV and radio broadcasts used to educate health workers and parents about ORT.

|

Learning about oral rebydration at the ORT centre in one of

the hospitals in Astrakhan, Soviet Union.

Analbsis of 250 case reports from the Regional Infectious Clinical Hospital's ORT

Centre showed that most cases were . in children under a year old who were given

artificial milk alone or in combination with breastmilk. Four fifths of patients were .

treated at home with WHO formula ORS solution, and the vast majority recovered within two

or three days.

|

|

An evaluation of the ORT centres after five years shows that:

- ORT is effective for in-patients;

- ORT units had been set up in all out-patient departments;

- hospital admissions for diarrhoea had decreased; and

- most mothers are aware of ORT and correct feeding practices.

But some actions are still needed:

- health workers and doctors need more training on ORT, as many of them are still using

intravenous drips unnecessarily, and on correctIy diagnosing the degree of dehydration;

paediatricians often use ORS onIy to prevent dehydration or during recovery, not to treat

dehydration;

- the supply of ORS packets should be improved to meet actual needs;

- the use of antibiotics, especially in rural areas, as a first-line treatment for acute

diarrhoea should be discouraged;

- breastfeeding should be more vigorously promoted.

Dr S Saroyants, Dr V Burkin, Dr G Dienko and Dr L

Chichkova, Institute of

Epidemiology, 416601, GSP, Astrakhan, USSR.

USA learns ORT lessons Diarrhoea is not just a cause of child death in developing countries. In the USA, 500

children under five die every year from diarrhoea - one every 18 hours. Many of these

deaths occur in poor communities with inadequate sanitation. More than 200,000 children

are taken to hospital with dehydrating diarrhoea every year. Intravenous therapy is the

standard treatment. This usually means several days in hospital, but in spite of this,

studies showed that half the children who died of diarrhoea did so in hospital. This may

have been because parents did not take the child to hospital soon enough or gave the child

inappropriate fluids at home. Most of these deaths could be prevented if oral rehydration therapy (ORT) were to 2 be

used. ORT has other advantages which are as relevant to the USA as to developing

countries:

- it is easy to give, at home as well as in hospital;

- it is inexpensive;

- it reduces the need for admission to hospital, thus reducing the costs to the national

health budget and to families.

Various organisations are co-operating to form the National ORT Project, to promote the

use of ORT in the USA. Dr Mathuram Santosham of Johns Hopkins University campaigned ten

years ago to promote ORT in a Native American Indian community in Arizona, USA, and child

diarrhoea mortality there was reduced to almost zero. He comments: 'We have been behind in

introducing this therapy. We ought to catch up with the developing world.' The cost in the USA of commercially available ORS, or ORT solutions (pre-mixed fluids).

is however very high. One litre costs between $4 and $6, and a dehydrated child usually

needs at least 4 litres. Reducing the cost would make promotion of ORT much easier. Johns

Hopkins Hospital has started to give people less expensive ORS packets based on the WHO

formula, and has found that these are acceptable to families and correctly mixed, if

proper education is given. Health staff resistance to using ORT quickly disappeared, when

they found that the time it takes to explain ORT to a family is far less than the 12 hours

or more needed to rehydrate a baby intravenously. Source: American Medical News, May 1991.

|

Scientific editors Dr Katherine Elliott and Dr William Cutting

Managing editor Kathy Attawell

Assistant editor Nel Druce DD thanks Hasan Shareef Ahmed (ICDDR,B) for help

with DD47 during his

stay at AHRTAG Editorial advisory group

Professor J Assi Adou (Ivory Coast)

Professor A G Billoo (Pakistan)

Professor David Candy (UK)

Professor Richard Feachem (UK)

Dr Shanti Ghosh (India)

Dr Michael Gracey (Australia)

Dr Nicole Guérin (France)

Dr Norbert Hirschhorn (USA)

Dr Sharon Huttly (UK)

Dr Claudio Lanata (Peru)

Professor Leonardo Mata (Costa Rica)

Dr Jon Rohde (USA)

Dr Mike Rowland (UK)

Ms E O Sullesta (Philippines)

Professor Dang Due Trach (Vietnam)

Professor Andrew Tomkins (UK) With support from AID (USA), ODA (UK), UNICEF, WHO Publishing partners

BRAC (Bangladesh)

CMAI (India)

CMU (China)

Grupo CID (USA)

HLMC (Nepal)

lmajics (Pakistan)

ORANA (Senegal)

RUHSA (India)

Consultants at University Eduardo Mondlane (Mozambique)

|

Issue no. 47 December 1991

Page Navigation

This edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online is produced by Rehydration Project. Dialogue on Diarrhoea was published four times a year in English, Chinese, French, Portuguese, Spanish, Tamil,

English/Urdu and Vietnamese and reached more than a quarter of a million readers worldwide. The English edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea was produced and distributed by Healthlink Worldwide. Healthlink Worldwide is committed to strengthening primary health care and

community-based rehabilitation in the South by maximising the use and impact

of information, providing training and resources, and actively supporting

the capacity building of partner organisations. - ISSN 0950-0235 Reproducing articles

Healthlink Worldwide encourages the reproduction of

articles in this newsletter for non-profit making and educational uses. Please

clearly credit Healthlink Worldwide as the source and, if possible, send us a copy of any uses made of the material.

|

updated: 23 August, 2019

updated: 23 August, 2019

|