|

| |

Issue no. 8 - February 1982

pdf  version of this Issue version of this Issue

|

There is much information in this issue that is valuable

and useful. Online readers are reminded, however, that treatment guidelines and health

care practices change over time. If you are in doubt, please refer to

WHO's up-to-date Dehydration Treatment

Plans.

|

Pages 1-8 Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 8 -

February 1982

|

DDOnline

Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 8 February 1982

Page 1 2

Page 1 2

Handle with care Our main article in this issue gives guidelines about drug therapy for diarrhoeal

diseases - which drugs to consider, how and when to use them and their mode of action. The

need for further research and more extensive clinical trials in this area is clearly

indicated. Stopping up the leak is wrong The idea of a drug which can 'turn off the tap' in diarrhoea has dangerous appeal.

Recent controversial publicity has highlighted the existence of preparations which claim

to have this effect. This is misleading. These drugs do not act in this way - their

questionable role is merely to reduce bowel movements by paralysing the gut. Such drugs

must never be given to small children for reasons explained by Professor Harold

Lambert on pages="#page4">four and five of this issue. Cautious prescription

Toxic effects of drugs, dangers of antibiotic resistance and damage to normal bowel

bacteria all underline the importance of a cautious approach in prescribing medicines for

diarrhoea. Replacement of fluid losses is always the first step. The possible use

of drugs comes afterwards and depends upon the probable cause of the diarrhoea and the

facilities available to confirm diagnosis. Laboratory techniques will be discussed in="dd11.htm">issue 11 of Diarrhoea Dialogue to be published in November

1982. Fluid losses must be replaced

The essential first aid treatment for diarrhoea, whatever the cause, is to replace

water and salts lost. This simple measure saves lives and is the only treatment necessary

for many bowel infections. Oral rehydration salts (ORS) solution can usually be given by

mouth. Intravenous drips and nasogastric tube rehydration are only necessary in very

severe dehydration where there is circulatory collapse, excessive vomiting or

unconsciousness.

|

Oral rehydration therapy:

the essential first-aid treatment for

diarrhoea.

|

The message stays the same In many cases of acute diarrhoea, therefore, the body will itself 'turn off the tap',

given sufficient fluid input to compensate for the stool output. Chronic diarrhoea,

however, has other implications and will be our main topic in a future issue of Diarrhoea

Dialogue. W.A.M.C and K.M.E

|

In this issue..

- Drugs and the treatment of diarrhoea

- Slide shows in Bhutan

- Storing oral rehydration salts

|

|

DDOnline

Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 8 February 1982

1 Page 2 3 1 Page 2 3

Children and sanitation

A recent evaluation of a primary school sanitation programme in Lesotho (1) found that

socio-cultural factors greatly reduced the health impact of the programme. Results showed

that:

|

This poster from the Ivory Coast explains that enemas are bad

for children.

- Only 10-15 per cent of school children used the new latrines daily. This in a society in

which frequent bowel movements are encouraged as a sign of good health, laxative and enema

abuse is widespread and diarrhoea is often endemic among the young during the hot, wet

summers.

- Children under eight or nine years old are actively discouraged by parents and teachers

from using the school pit latrines.

- Children's reasons for not using the latrines included the bad smell, wobbly squatting

slabs, lack of privacy and fear of bullying by older children.

|

|

The evaluation recommends that to encourage children to use latrines:

- latrine designs should be better suited to the needs of rural children.

- health education campaigns aimed at parents and children are vital.

- local attitudes and practices should be incorporated into the latrine construction

programme.

(1) Socio-Cultural Evaluation of the Primary School Sanitation Project 1981.

Technology Advisory Group, World Bank, Washington. Further information on the evaluation

is available from Piers Cross, Evaluation and Planning Centre, London School of Hygiene

and Tropical Medicine, Keppel Street, London WC1E 7HT, UK.

|

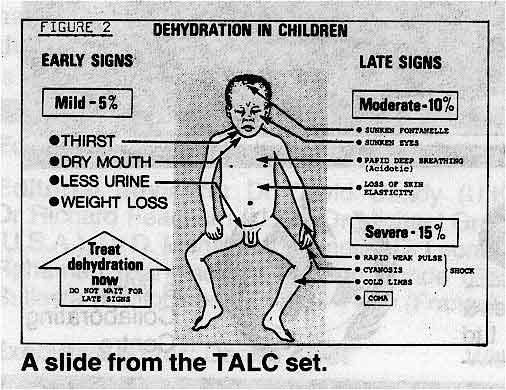

Slide sets

|

A

set of 24 slides and text on the clinical management of diarrhoea is shortly to be

published by Teaching Aids at Low Cost (TALC). The set is aimed at nurses and medical

assistants and contains comprehensive information on the management of diarrhoea with oral

rehydration fluids, as well as useful hints on the most effective way of using slide sets. If you would like to order one or more sets. write to TALC, P. O. Box 49, St. Albans,

Herts, UK.

|

|

Prices:

|

| Slide sets |

Europe

N. America

Australia |

Rest of the world |

| Unmounted |

£1.80 |

£1.10 |

| Mounted (in cardboard frames) |

£2.50 |

£1.75 |

| Mounted and in plastic wallets |

£4.25 |

£3.50 |

All prices include packing and postage |

Publications

The UNICEF Home Gardens Handbook

Newly published by UNICEF and available free from their offices, this handbook promotes

home gardens as a valuable part of any country's nutritional improvement programmes. Even in towns and cities, where conventional garden space may not be available, useful

contributions to family meals can still be grown, using pots, trellises and rooftops in an

imaginative, 'vertical' way. Focus on ORT

| This is the new

logo being used by the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh

(ICDDR, B) and illustrates the importance placed by the Centre on oral rehydration therapy

in the management of diarrhoeal diseases. |

|

Rice powder research

Readers who have written to ask us whether any further research has been carried out on

the usefulness of rice powder as an alternative to sucrose in oral rehydration solution

will be interested to learn that Dr Majid Molla and his colleagues at ICDDR, B have

produced further information on this subject. The findings will be published in a

forthcoming issue of The Lancet but in the meantime are available in issue 11

(volume three) of Glimpse, the newsletter published by ICDDR, B. You can obtain a

copy by writing to Shereen Rahman, ICDDR, B, P. O. Box 128, Dacca 2, Bangladesh.

|

|

DDOnline

Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 8 February 1982

2 Page 3 4 2 Page 3 4

Slide shows in Bhutan

Paramedical workers in basic health care units near Bumthang are being taught with

slide shows and simple text about the causes of diarrhoea and main control measures.

|

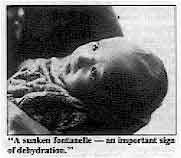

"A sunken fontanelle - an important sign of dehydration."

Dr Peter Leisinger and his colleagues at the Bumthang Hospital have prepared a slide

show, using photographs taken in the communities where the material will be used, and a

basic text on the main causes of diarrhoea.

|

|

"Dirty

feeding bottles - a cause of diarrhoea."

They have found that health workers are much more receptive to the messages that being

put across when they are illustrated with familiar photographs.

|

|

|

"A dehydrated child."

If you have access to a slide projector and can take some photographs in your

community, this form of health education for teaching both health workers and mothers can

be very useful.

|

You may be able to use selected slides from other sets along with your are own pictures

to illustrate teaching about diarrhoea (see="#page2">news page).

"Dirty bamboo tubes used for carrying

drinking water- a major health

risk." |

"The

signs of dehydration." "The

signs of dehydration."

|

These illustrations are taken from the Bhutanese slide set.

|

|

DDOnline

Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 8 February 1982

3 Page 4 5 3 Page 4 5

| Drugs and the treatment of diarrhoeal diseases |

Cautious prescription

Professor Harold Lambert explains the clinical

situations which justify the use of drugs in addition to oral rehydration therapy.

|

Two main groups of drugs are

commonly prescribed in the treatment of diarrhoeal diseases:

- Antimicrobial drugs - which kill the responsible organism and so lessen the illness.

- Antidiarrhoeal drugs - which diminish the amount of fluid loss by various

pharmacological mechanisms.

These two types of drugs are often combined and many preparations are marketed

containing both antibiotics and antidiarrhoeal drugs. These combination drugs should never

be used. Only single drugs should be given and only where appropriate.

|

|

Antibiotics should only he used:

- When there is clear clinical suggestion of invasive diarrhoeas (bloody stools and high

fever) or cholera (in a cholera-endemic area).

- Or when laboratory results become available and indicate the need for antibiotic

treatment.

|

Antibiotics in bowel infections

For certain specific infections of the gut an appropriate antimicrobial drug is an

important part of the treatment. Shigella infection:

In mild, transient diarrhoea caused by shigella, antibiotic treatment may be unnecessary

as, for example, in mild Sonne or flexneri dysentery. Antibiotics are, however, an

essential part of the treatment of severe bacillary dysentery, especially in infants with

persistent high fever. Choice is difficult because transferable drug resistance has become

very common in these organisms and local knowledge of their drug susceptibility has to be

taken into account. Ampicillin or co-trimoxazole are usually suitable (ampicillin

l00mg/kg/day in four divided doses for five days, or trimethoprim 10mg and

sulfamethoxazole 50mg/kg/day in two divided doses for five days). Single dose treatment in

adults with tetracycline (2.5g) is also very effective if the bacilli are known to be

susceptible to this drug. Campylobacter infection:

Campylobacter jejuni may invade the bowel wall causing abdominal pain and

mildly dysenteric stools. Most cases recover well without chemotherapy. Severe cases may

be treated with erythromycin (40mg/kg/day in three divided doses for five days) but its

efficacy is unproved. A recent controlled trial showed no clinical benefit from

erythromycin but treatment was not started until an average of six days from the onset of

illness (1). Cholera:

Several antibiotics, particularly tetracycline, have been shown to shorten the duration of

the disease and are therefore useful in the management of cholera patients. Tetracycline

is given as 50mg/kg/day in four divided doses for three days. Drug resistance is now being

seen in areas where mass chemoprophylaxis has been carried out. Alternative drugs include

furazolidine and chloramphenicol. Enterotoxigenic and enteropathogenic E. coli:

Relatively few clinical trials have been done on the effect of antibiotics in this group

of bowel infections. Enterotoxigenic E. coli generally cause acute episodes of

relatively brief duration, making antibiotics unnecessary. Because of the difficulty in

identifying these organisms, there seems to be little justification at the moment for

treating them with antibiotics. Similarly, for enteropathogenic E. coli, there is

no clear evidence that antibiotics are beneficial. Salmonella infections:

For the vast majority of acute diarrhoeal illnesses caused by non-typhoid Salmonella

strains, antibiotics do not change the course of illness and may actually prolong the

period during which stool cultures remain positive. Salmonella septicaemia, which may

present in childhood as a combination of diarrhoea with systemic illness and fever

requires antibiotic treatment. Ampicillin, chloromycetin, or co-trimoxazole may be used,

depending on the sensitivity of the organism. Amoebiasis and Giardiasis:

Both these parasitic infections respond to several antimicrobial agents. Metronidazole is

the first choice for either.

|

|

DDOnline

Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 8 February 1982

4 Page 5 6 4 Page 5 6

| Drugs and the treatment of diarrhoeal diseases |

Antibiotics in bowel infections of unknown cause

The cause of many bowel infections is never identified, or the organism may be found

after the acute illness is over. Antibiotics have no role in the treatment of the large

group of viral diarrhoeas. It has sometimes been suggested that antibiotics should

routinely be prescribed in case the illness turns out to be due to an infection for which

antibiotic treatment is indicated. This practice is to be avoided for several reasons:

- The giving of antibiotics may divert the attention of mother and nurse from the

essential task of replacing water and electrolytes.

- The widespread use of antimicrobials promotes the selection of antibiotic resistant

strains and thus lessens the likelihood that the drugs will later be effective for those

few patients who need them.

- Antibiotics are expensive. The balance of factors therefore clearly lies against the

blind use of antibiotics in diarrhoeal disease of unknown origin.

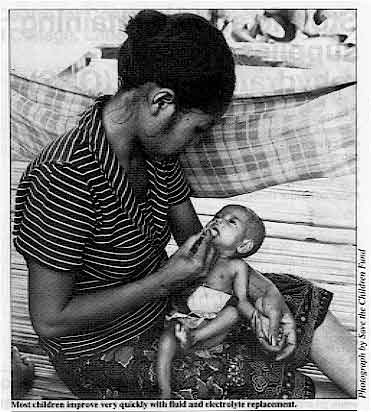

Other drugs in gastroenteritis

The most commonly used agents are kaolin and pectin in one or other of many available

preparations, despite clinical trials proving lack of efficacy. Most children improve so

quickly with fluid and electrolyte replacement that the use of 'constipating agents' is

unnecessary in acute diarrhoea. Drugs such as opiates, diphenoxylate and loperamide which reduce bowel motility,

although widely used, should never be given to children. By slowing peristalsis

they make the situation worse - this has been seen in a number of children and in

volunteers with shigellosis. These drugs also depress respiration and are an important

cause of accidental poisoning in childhood. Research

|

Most children improve very quickly with fluid and electrolyte

replacement.

Several research projects are underway aiming to find drugs which will reduce the

abnormal transport of fluid across the small bowel mucosa. For example, anti-inflammatory

drugs (aspirin and indomethacin) may decrease the action of cholera and other toxins

acting on the bowel. Bismuth subsalicylate, in large doses, has been beneficial in adults

with travellers' diarrhoea. Other substances have also been tried; for example, chlorpromazine, which probably

inhibits adenylate cyclase, was shown to reduce diarrhoeal losses in cholera. However,

since it may cause drowsiness in children, and hence a decrease in fluid intake. it is

unsuitable for widespread use. Attempts have also been made to prevent cholera toxin

binding to the bowel wall, but these studies have not shown the method to be useful in

practice.

|

|

None of these experimental drugs have reached a stage where they can be recommended for

general use in patients with diarrhoea. If drugs which reduce intestinal secretion become

better defined, and can be shown to be effective in field conditions against diarrhoea

caused by a broad range of aetiologic agents, they will be useful adjuncts to therapy. Conclusion

Oral rehydration therapy remains the essential treatment and antibiotics are useful

only in the few clinical situations described. Professor H. P. Lambert, Communicable Diseases Unit, St. George's Hospital, London,

UK. (1) Anders B J et al 1982 Double-blind placebo controlled trial of erythromycin for

treatment of campylobacter enteritis. The Lancet January 16: 131-132.

|

|

DDOnline

Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 8 February 1982

5 Page 6 7 5 Page 6 7

Storing and maintaining

supplies of oral rehydration salts (ORS)

Whether a country is producing ORS locally or using UNICEF sachets, the product

must be properly stored so that it remains effective from the time it is delivered to the

central store to the moment it is used. Sodium bicarbonate causes decomposition of glucose

in oral rehydration salt mixtures. High temperatures and humidity may accelerate this

process and manufacturers must consider these factors when preparing and packing ORS. Storage

|

Preparing

sachets of ORS in Bangladesh.

- Temperatures in buildings where ORS is stored should not exceed 30°C. Above this

temperature the ORS may melt or turn brown. If this happens, it may be very difficult to

dissolve and should not be used. If, however, it has only turned yellow, as long as it can

be properly dissolved, it is still safe to use and effective.

- Supplies of ORS should not be stored in buildings with galvanized roofs directly exposed

to the sun without adequate ventilation. These rooms get very hot.

|

|

- Humidity in stores should not exceed 80 per cent. In higher humidity the ORS is likely

to cake or turn solid. Increase ventilation and avoid standing water in or near storage

rooms.

- As far as possible, storage areas should be cleared of insects and rodents.

- Packets should be packed so they are protected from puncturing by sharp objects.

- UNICEF recommend storing their ORS sachets in stacks of cartons approximately 1 to 1½

metres high.

- A rotating system should be introduced so that the oldest ORS (identified by date and

batch number) is used first. When in a hurry, avoid distributing the packets which are at

the front or the top unless you are sure they are the oldest in the store.

- Regional storage areas should be located in places that will be convenient for

subsequent distribution.

Regular inspection of packets

- Laminated foil ORS packets have an estimated shelf life of at least three years. Note

the production date on the label. Packets of ORS must be checked regularly (every three

months) to see if the quality is still acceptable. Open at least one packet in each batch

to see if the ORS is usable. Locally produced packets of ORS are often packaged in plastic

and will probably have a shorter shelf life. It is especially important to check them

regularly.

- Check ORS packets in any boxes that appear to be damaged. Open at least one packet from

the top, middle and bottom of the box to see if the ORS is still usable.

Keeping records at each point where ORS is received and delivered.

- Records should show:

- the quantity, batch number or letter, and date received.

- the quantity and date issued (i.e. sent from one point in the distribution system to

another).

- the amount currently in stock.

- stock level at which a new supply should be requested.

- Records should also indicate any problems (such as spoilage due to a leaking warehouse).

- Supplies should be counted every three months and results compared with quantities shown

in the records.

- The evaluation of stock is an important factor in determining future quantities of ORS

required.

If you are interested in further information on local production of ORS and quality

control, the following publications are available from the Programme Manager, CDD

Programme, World Health Organization, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland.

- Guidelines for the production of oral rehydration salts.

- Good practices for the manufacture and quality control of drugs.

|

|

DDOnline

Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 8 February 1982

6 Page 7 8 6 Page 7 8

WHO-EMR Training Centre for Control of Diarrhoeal Diseases,

King Edward Medical College, Lahore, Pakistan.

Diarrhoea is the most common childhood disease in Pakistan. It accounts for half of all

hospital admissions and one third of all outpatient visits of children under five years of

age. It is estimated that 14 million episodes of diarrhoea occur each year in Pakistan and

that more than 100,000 pre-school children die as a result of the disease. Oral rehydration therapy (ORT)

|

Oral

rehydration at King Edward Medical College.

Several studies carried out during the mid-seventies in paediatric centres in Pakistan

have highlighted the advantages of ORT and promoted its acceptance by the medical

profession. Intensive efforts are now underway to train medical and paramedical staff in the use of

ORT. A training centre for the control of diarrhoeal diseases was established in November

1980 at King Edward Medical College, Lahore, within the Department of

Paediatrics. This is

a national centre but also a regional base for the Eastern Mediterranean Region office of

the World Health Organization. The Centre is associated with the College's large

in-patient and out-patient paediatric facilities, including an enteric diseases ward which

provides an excellent opportunity for teaching and training in the management of

diarrhoea.

|

|

Five courses

The Centre has already held five courses, each lasting nine days, and covering basic

microbiology, pathophysiology, epidemiology and the clinical treatment of diarrhoea.

Ninety-six physicians have so far been trained. The courses will be offered several times

each year and special shorter courses are also being organized for paramedical personnel

and hospital administrators. It is expected that the continuing activities of the Centre will reduce mortality rates

due to diarrhoea by more than 75 per cent over five years, The need for hospitalization

and the present high cost of treating diarrhoea should also be considerably reduced. Professor Shaukat Raza Khan, Director, Training Centre for the Control of Diarrhoeal

Diseases, Lahore, Pakistan.

Indonesia: Inter-regional Training Course for Managers of National

Programmes for Control of Diarrhoeal Diseases.

|

Studying on the training course in West Java.

The sixth WHO training course for national programme managers was held between 25

January and 3 February in Cipanas, West Java. Participants came from 17 different

countries including Indonesia, Liberia, Kenya, Nepal, Papua New Guinea and Vietnam. As

with previous courses, the aim of the Cipanas meeting was to provide participants with

management skills which they could apply at home in setting up and managing national CDD

programmes.

|

Theory and practice

Discussions with course facilitators and other participants helped to link the

theoretical problems in the training materials to particular situations that each manager

would face at home. Plenary sessions were held on the clinical use of ORS, health

education, research needs in CDD and evaluation. Participants also had the opportunity of

visiting a factory producing ORS and an oral rehydration unit at a health centre.

|

|

DDOnline

Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 8 February 1982

7 Page 8 7 Page 8

Editors' note:

The following letter has come from UNICEF in reply to correspondence in="dd07.htm">Diarrhoea Dialogue 7 about the lack of one litre bottles for measuring

ORS in Nicaragua. The problem of mothers being unable to measure a volume of one litre accurately is one

that has been discussed before and as far as I know no-one has come up with a really good

answer. In some countries, and this may be true of Nicaragua, bottles of soft drink that

measure one litre may be widely available. Rather less satisfactorily 500 ml bottles can

be used as a means of measuring water into a pan or mixing bowl of some sort. This relies

on practical demonstration using whatever is commonly available in the community.

|

Bangladesh: solving a problem.

We have thought of - and even tried on a pilot scale - issuing one litre plastic jugs,

but that is too expensive, down to simple polythene bags as a disposable measure but that

does not seem to be too satisfactory either. If any readers come up with better ideas, we

should be very interested to hear them.

|

It is of course possible to pack a proportionately smaller amount of powder into each

sachet to make up a half or even a quarter litre of solution - that is probably more

convenient, but it is also more expensive, and therefore we have not done this in UNICEF.

Nonetheless, other people have - as an example, Laboratories Raven S. A. in Costa Rica

produce packets of ORS under the name SUERORAL which are to be diluted with 240 ml of

water and consist of:

| Sodium chloride |

0.84g |

| Potassium chloride |

0.54g |

| Sodium bicarbonate |

0.60g |

| Dextrose |

4.8g |

Other countries in Central America that are producing ORS sachets for

one litre are Honduras (PANI) and El Salvador (Laboratories Carosa) and in Guatemala

(Abbott Laboratories) produce an expensive solution (about US$ 2.00 for 400 ml bottle).

All these alternatives are, however, more expensive, usually very considerably so, than

the UNICEF ORS sachets. In order to be able to produce the maximum amount of ORS for the available funds,

UNICEF has produced its standard formula - we believe it is better to make it available to

the maximum number of children in the world rather than make a more expensive product that

can only reach fewer children. Roger M. Goodall, Chief, Supply Specifications Section, UNICEF, New York, USA

Editors' note: A letter from Dr W. B. Greenough III, Director of the International Centre for

Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (ICDDR, B), prompts the editors to clear up any

possible misunderstanding, following Dr David Candy's article in Diarrhoea

Dialogue 7, about the effectiveness of oral rehydration therapy in diarrhoea due to

rotavirus infection. Dr Greenough comments that "The key to the success of oral rehydration in

cholera and other diarrhoeal diseases is that a carrier molecule, usually glucose, makes

use of a pathway for absorption by the lining cells of the gut which is different from

the pathway by which salt and water is usually absorbed. This pathway remains intact not

only in diarrhoea due to enterotoxins, such as those produced by Vibrio cholerae and

E. coli, but also in the case of rotavirus - where the destruction of cells is

limited to the villus tip cells and does not affect other cells capable of utilizing

carrier mediated transport for salt and water."

Cuban interest

I am Professor of Paediatrics of the Faculty 1, Superior Institute of Medical Sciences,

Havana City, and work at the "Pedro Borras" Children's Hospital, Vedado, Havana

City as head of the Gastroenterology Department. In the past few days and for the first time, came into my hands a copy of your Diarrhoea

Dialogue which I found most valuable. Even though in my country this disease is

not any more the first cause of mortality in infancy, and the morbidity has decreased

considerably, we still consider it of high interest from both the practical and the

scientific point of view. Dr Antonio de Armas, P. O. Box 6204, Vedado Plaza, Havana, Cuba

Editors' note: A Spanish edition of the newsletter (Diálogo sobre la Diarrea) is available.

To be put on the mailing list contact Mr M. McQuestion, Pan American Health Organization,

525 Twenty-Third Street NW, Washington DC 20037, USA.

Clinician's guide to aetiology Diarrhoea Dialogue contains very useful practical knowledge especially for

people working in rural areas in developing countries. You asked for comment on the

clinician's guide in Diarrhoea Dialogue 7. The guide is very

useful for rural health workers who are exposed to the very first signs of the most common

conditions. It offers a quick guide at a glance. Please include more of such clinician's

guides in future. C. O. Kondo, Wajir District Hospital, P.O. Box 2, Wajir, N.E.P., Kenya

|

Scientific editors Dr Katherine Elliott and Dr William Cutting

Executive editor Denise Ayres Editorial advisory group

Professor David Candy (UK)

Dr I Dogramaci (Turkey)

Professor Richard Feachem (UK)

Dr Michael Gracey (Australia)

Dr Norbert Hirschhorn (USA)

Dr D Mahalanabis (India)

Professor Leonardo Mata (Costa Rica)

Dr Mujibur Rahaman (Bangladesh)

Dr Jon Rohde (USA)

Ms E O Sullesta (Philippines)

Dr Paul Vesin (France)

Dr M K Were (Kenya) With support from WHO and UNDP

|

Issue no. 8 February 1982

Page Navigation

This edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online is produced by Rehydration Project. Dialogue on Diarrhoea was published four times a year in English, Chinese, French, Portuguese, Spanish, Tamil,

English/Urdu and Vietnamese and reached more than a quarter of a million readers worldwide. The English edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea was produced and distributed by Healthlink Worldwide. Healthlink Worldwide is committed to strengthening primary health care and

community-based rehabilitation in the South by maximising the use and impact

of information, providing training and resources, and actively supporting

the capacity building of partner organisations. - ISSN 0950-0235 Reproducing articles

Healthlink Worldwide encourages the reproduction of

articles in this newsletter for non-profit making and educational uses. Please

clearly credit Healthlink Worldwide as the source and, if possible, send us a copy of any uses made of the material.

|

updated: 23 August, 2019

updated: 23 August, 2019

|