|

| |

Issue no. 12 - February 1983

pdf

version of this Issue version of this Issue

|

There is much information in this issue that is valuable

and useful. Online readers are reminded, however, that treatment guidelines and health

care practices change over time. If you are in doubt, please refer to

WHO's up-to-date Dehydration Treatment

Plans.

|

Pages 1-8 Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 12 -

February 1983

|

DDOnline

Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 12 February

1983  Page 1 2

Page 1 2

Cholera tamed by ORT

|

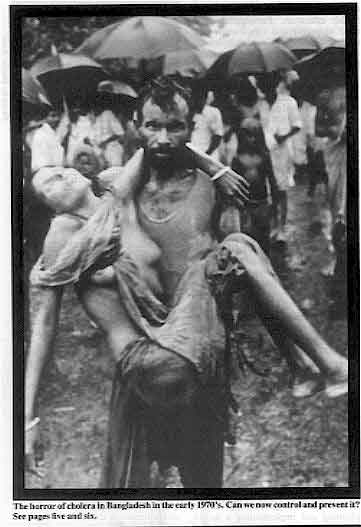

The

horror of cholera in Bangladesh in the early 1970's. Can we now control and prevent it?

See pages="#page5">five and six. This issue marks the 100th anniversary of the identification by Robert Koch of the

organism responsible for the death of millions. A crucial part of the cholera story is the

triumph of oral rehydration therapy (ORT) which began in Calcutta and Bangladesh just over

12 years ago. "They came in, carried or supported by their relatives and lay down . . . they

voided their bowels where they lay . . . the cramps spread upwards from the calves to

tighten the thin thighs and to knot the flaccid bellies . . . they gulped thirstily and, a

minute later, would vomit up what they had drunk. They shrank as the substance was drawn

from every part of the body and pushed out in those convulsions. Noses became pointed . .

. skin wrinkled and had no resilience. When those signs came, they had neither fear of

death nor will to live." Such was cholera in 1856 as described in a novel about Bengal by John Masters.

|

No one has to die from dehydration caused by any diarrhoeal disease provided someone

knows how to give enough oral rehydration correctly. Prevention of cholera can be summed up quite simply with the saying 'You can drink

cholera and you can eat cholera, but you cannot catch it'. Food and water must be kept

safe from contamination with faeces or vomit and hands kept clean at all times. Health

education can help to eliminate the causes of diarrhoeal diseases like cholera. Meanwhile

ORT can prevent unnecessary suffering and deaths. K. M. E.

|

In this issue...

- Cholera: history, research and control

- The role of intestinal parasites in the chronic diarrhoea/malnutrition syndrome

- News and reviews

|

|

DDOnline

Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 12 February

1983  1 Page 2 3 1 Page 2 3

| The children's revolution The recent announcement by James Grant,

Executive Director of UNICEF, that the organization intends to put its resources even more

firmly behind the promotion of oral rehydration therapy (ORT) and breastfeeding is welcome

news. Collaboration between UNICEF and the diarrhoeal disease control programme of WHO is,

of course, not new. The two organizations have promoted the use of ORT for several years,

with WHO focusing more on training and management and UNICEF concentrating on production

and supply of oral rehydration salts (ORS). Nevertheless, this new initiative,

particularly in the whole area of communications and diarrhoeal disease control, will

undoubtedly help to stimulate far more widespread use of ORT with far-reaching

implications for child health in developing countries. |

Cooperating on communications

A crucial aspect of communications and diarrhoeal disease control is that different

people working on programmes have the opportunity to meet and discuss the best ways of

confronting the problem together. We report below on two meetings that have taken

place recently to encourage this kind of cooperation: Dominica: health education in schools Two seminars were held recently in the Dominican Republic to look at ways of preventing

typhoid and other diarrhoeal diseases - especially in schools. The seminars were sponsored

by UNICEF, in collaboration with the Ministry of Health, and attended by principals of

schools and health educators. Typhoid is endemic in Dominica and research has shown that the disease is transmitted

mainly by food. A health education drive stressing personal hygiene, therefore, could do

much to reduce the high incidence of the disease. Participants at the seminar discussed the best way of promoting personal hygiene both

at home and in schools. Constraints such as shortage of water and the best ways of

overcoming these problems were also considered. The importance of preventing diarrhoea in children was stressed by health educators.

Participants practised preparing oral rehydration fluid using both UNICEF oral rehydration

salts (ORS) and locally available ingredients.

A final technical session looked at the importance of breast-feeding and diet in the

treatment and prevention of diarrhoea. School principals and health educators had not

discussed these issues together and all the participants found the meeting very useful.

They produced the following recommendations:

- improvement of school facilities - especially water and sanitation

- wearing of official identification badges by all approved food handlers

- use of more printed materials on health issues in schools.

Report sent to Diarrhoea Dialogue by Marese O'Dwyer, Health Education

Unit, Primary Health Care Centre, Upper Lane, Roseau, Dominican Republic. Rio de Janeiro: communications workshop A workshop on communications and diarrhoeal disease control was held from 29 November

to 10 December 1982 in Rio de Janeiro. Organized by the Pan American Health Organization

(PAHO) and the Centro Latinoamericano de Tecnologia Educational para la Salud

(NUTES/CLATES) the workshop was attended by participants from ten South American

countries. Two people came from each country and they included paediatricians, public

health staff, nurses, health educators and artists. The aim of the workshop, the first of its kind, was to suggest an approach to planning

and implementing a health education programme for diarrhoeal disease control. Work

included discussions on adapting the 'social marketing' approach to health education

(looking at analysis of target audiences, message formulation, pre-testing of materials

and selection of media etc); production of some health education materials; and the

development of guidelines to encourage participants to prepare a national workplan for a

communications programme for diarrhoeal diseases.

|

Discussing

posters produced at the workshop

The workshop was organized so that participants worked in both small groups and plenary

sessions. Many people had already been involved in health education programmes and had

much useful experience to share. Great emphasis was laid on the pre-testing and evaluation

of materials - frequently left out of health education programmes.

|

|

Participants at the workshop will now develop programmes in their own countries,

supported by PAHO. It is hoped that they will meet again at the end of 1983 to compare

progress achieved. During the year, the representatives from each country will also keep

in touch with their counterparts elsewhere to share experiences as they develop their

programmes. The communications workshop could well be of use in other parts of the world and the

diarrhoeal disease control programme of the World Health Organization is considering

whether this might happen. Two-way radio newsletter

Ned Wallace, of Development Technologies Ltd, has told us about a newsletter his

organization is starting this spring. The new publication will contain information about

use of two-way radio for rural health care in developing countries. There will be

information on equipment and the newsletter will also offer an inquiry service. If you

would like to be put on the mailing list write to: Marshall Cook, Editor, TWR Newsletter.

4337 Felton Place, Madison. WI 53705, USA.

|

|

DDOnline

Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 12 February

1983  2 Page 3 4 2 Page 3 4

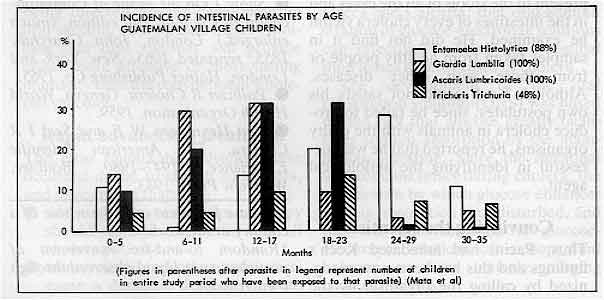

Causes or contributors?

Previous issues of Diarrhoea Dialogue have looked at the diagnosis and

treatment of some intestinal parasites. Andrew Tomkins now

considers their real significance in the chronic diarrhoea/malnutrition syndrome in

children. Many children in developing countries excrete parasites. Some are easily visible, for

example the adult worm of Roundworm (Ascaris lumbricoides) looks like an earthworm.

Others such as Giardia lamblia can only be seen by microscopic examination. Most

children in areas with inadequate sanitation experience an infection with Entamoeba,

Ascaris, Giardia or Trichuris during early childhood. Since many children also

have diarrhoea and are underweight it is tempting to blame the parasites. However, we

should ask whether they really cause disease.

Parasites can react with the intestine in several ways: Damage to the intestinal mucosa Giardia lamblia, Strongyloides stercoralis, Capillaria philippinensis and Cryptosporidium

destroy cells of the intestinal mucosa so that nutrient malabsorption occurs leading

to deficiencies of protein, energy, Vitamin A and folic acid. Mucosal damage causes

secondary lactase deficiency which makes diarrhoea worse if milk feeds, other than

breastfeeding, are continued. It seems that intestinal damage is most severe during the

first infection; the intestinal effect in subsequent infections is milder, suggesting the

development of some immunity. When immunity becomes weak, as in children with marasmus or

kwashiorkor, the parasites multiply. This is especially dangerous with Strongyloides which

actively invades the intestine. Decreased digestion Increased faecal losses of nitrogen and energy occur in children with heavy Ascaris infections

(though light infections have little effect). Giardia interferes with the process

which makes dietary fats soluble. A further problem is that bacteria colonise the upper

intestine during some intestinal infections. They may also decrease digestion of

nutrients. Loss of body fluids Many types of diarrhoea cause loss of body salts and minerals but certain parasites, Entamoeba

in particular, also cause loss of blood and proteins from the damaged intestinal

mucosa. Loss of appetite Food intake may be reduced by over 30 per cent during the prolonged diarrhoea caused by

some parasites. In severe giardiasis there is abdominal distension and discomfort due to

the malabsorption. In heavy infection with Ascaris there may be abdominal colic. Strongyloides

can cause abdominal pain and irritant skin rashes. Trichuris may cause painful

rectal prolapse. All these factors make a child miserable and unless he can be persuaded

to eat he will lose weight. Effect of treatment There are several factors to be considered: First, the nutritional status and diet. If the child is moderately well nourished and

fed, it is unlikely that treatment will be followed by weight gain. However, if he is

clinically malnourished and on an inadequate diet, the same degree of parasitic infection

is more serious and treatment can improve nutritional status. Second, the dose of infection. It is difficult to measure this accurately but, in Ascaris

infection, it is only children with heavy infection who show significant improvement

in growth after infection has been treated. Similarly, children with severe diarrhoea and

many trophozoites of Giardia show a more striking improvement in growth after

treatment than those children who are merely cyst carriers. Who should be treated?

However desirable it is to treat all infected children, mass treatment is unlikely to

be cost-effective. It is probably best to target treatment towards specific groups of

children. These would include those with clinical malnutrition or those with severe growth

faltering, those with obvious clinical symptoms of giardiasis (prolonged diarrhoea) or

amoebiasis (dysentery), any child with Strongyloides and those with especially

heavy infection with Ascaris. Unanswered questions

The introduction of oral rehydration therapy has drastically reduced mortality from

acute diarrhoea but many children are still dying from the protracted

diarrhoea/malnutrition syndrome. There are many unanswered questions about the role of

intestinal parasites in this syndrome. Perhaps you have some answers. Diarrhoea

Dialogue would be pleased to hear from you. Dr Andrew Tomkins, Senior Lecturer, Department of Human Nutrition, London School of

Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, U.K. Formerly at M.R.C. Laboratories, Fajara, The Gambia,

W. Africa. Mata L Jet al 1977 Effect of infection on food intake and the nutritional state:

perspectives as viewed from the village. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 30:

1215-1227.

|

|

DDOnline

Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 12 February

1983  3 Page 4 5 3 Page 4 5

| Confronting a killer: 100 years of research on cholera |

The devastating disease

Abram Benenson reviews the history of cholera and those

who discovered its cause. Cholera was first reported in the Indian subcontinent in the 17th century and, as far

as we know, remained mostly in the Bengal area until 1817 when it began to spread to other

parts of the world in 'pandemics'. * The first pandemic began in 1817 and spread throughout Asia. The second began in 1829

and cholera spread into the West, entering Russia in 1830, England in 1831, and crossing

the ocean to Canada and the United States in 1832. Cholera was a new disease, causing

consternation and havoc as it spread. In some communities, as many as 15 per cent of the

population died in cholera epidemics. Many considered the disease to be a divine

infliction, correctable by appropriate devotions and proper living. Hunting the organism More scientific thought, however. was given to the problem when a second wave of

disease hit Europe. In 1849. John Snow published the famous pamphlet in which he argued

that the disease was transmitted by faecal wastes in water. During the third pandemic,

which hit England in 1853- 54, Snow was able to prove the association between drinking

faecally contaminated water and the development of cholera. He claimed the disease was

caused by 'morbid matter' which entered the body through the mouth and multiplied during

the incubation period. In 1849, Budd claimed that a distinct species of fungus, when

swallowed, would cause the disease. Pacini reported from Italy in 1854 the presence of

curved organisms in the intestinal contents of cholera victims. These organisms had a

darting motility far surpassing that of Brownian movement.** He called the organisms Vibrio

cholerae, but his publication of these findings rested quietly in the Italian

literature. Subsequently other workers observed and described such organisms but the

scientific world remained unconvinced. The fourth pandemic

The fourth pandemic started in 1863 and killed half a million people in Europe over the

next ten years. The cause of this devastating disease needed to be clearly defined.

Distinguished scientists, such as Pettenkofer, maintained that cholera was caused by

airborne emanations from suitable soils. Macnamara, a British ophthalmologist who was

convinced that a specific aetiological agent was causing cholera, was refused permission

to go to India for further studies. However, Robert Koch headed a German Commission and

Roux a French Commission which went to seek the aetiological organism in Egypt, which had

been invaded during the fifth pandemic in 1881. The French group tried to isolate the

organism by animal inoculation. Koch used the bacteriological techniques which he had

developed and succeeded in isolating a suspect organism. When the disease disappeared from Egypt, Koch went to India and demonstrated that the

suspect organism was present in the stools of all the cases and in the intestines of every

cholera victim he examined. He did not find it in samples taken from healthy people or

from those with other diseases. Although Koch could not satisfy his own postulates, since

he failed to produce cholera in animals with the guilty organisms, he reported that he was

successful in identifying the aetiological agent. Convincing the scientists

Thus, Pacini had antedated Koch's findings and this has been now recognized by calling

the organism by the name he gave it (Vibrio cholerae). Snow had identified the

faecal-oral transmission of the disease, and the important part played by

faecally-contaminated water. But Koch was the one who succeeded in convincing the

scientific world of these truths, and put to rest the conflicting and false concepts

supported by very influential scientists. It is 100 years since the issue has been settled. Since then there have been two

pandemics. The sixth lasted from 1899 to 1923, largely in Eastern Europe. The seventh, and

current, pandemic started in 1958 in Sulawesi and spread to reach Europe by 1965. It has

provided the impetus for the initiation of exciting studies by many scientists on the

pathogenesis, immunology, treatment and prevention of cholera. Out of these studies have

come the techniques for successful management of the disease, especially oral rehydration

therapy, described in previous issues of Diarrhoea Dialogue, the effectiveness of

appropriate antibiotics in eliminating infectivity, and the role which can be played by

available vaccines. These studies, largely centred in the Pakistan - SEATO Cholera

Research Laboratory (now the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research,

Bangladesh), have converted a terrible disease with a case fatality rate among

hospitalized cases of 20 per cent and higher to an easily managed illness with death

occurring in less than one per cent. Professor Abram Benenson, Head, Division of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Graduate

School of Public Health, San Diego University, USA. Further reading:

- Snow J On the Mode of Communication of Cholera. 2nd edition, (much enlarged.) London,

John Churchill, 1855; reprinted 1965, New York and London, Hafner Publishing Co, 1965.

- Pollitzer R Cholera. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1959.

- Van Heyningen W E and Seal J R Cholera, The American Scientific Experience,

1947-1980. Boulder, Westview Press, 1983.

*Disease prevalent over the whole of a country or the world **Random to-and-fro movement of particles in any liquid observed through a

microscope.

|

|

DDOnline

Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 12 February

1983  4 Page 5 6 4 Page 5 6

| Confronting a killer: 100 years of research on cholera |

Recent developments

The treatment of cholera has progressed considerably since the first pandemic

spread out of India in 1817. Charles Carpenter highlights the

key advances. The central key to our current understanding of cholera was the 1959 demonstration, by

S. N. De in Calcutta, that the massive intestinal fluid losses in cholera are directly

related to the action of an enterotoxin, caused by cholera vibrios, on the intestinal cell

wall. Subsequent studies have:

- demonstrated that the same enterotoxin is produced by all pathogenic strains of V.

cholerae

- defined the chemical structure of the enterotoxin

- identified the molecular pathways by which the enterotoxin causes fluid secretion by the

intestine.

There is no other bacterial infection in which pathogenetic events have been so

precisely defined. Vaccine research

However, despite this, no effective vaccine has yet been developed. Carefully

controlled field trials, carried out in Bangladesh and the Philippines in 1963, clearly

demonstrated that conventional whole-cell vaccines, consisting of killed micro-organisms,

provide only limited (40 per cent to 70 per cent) protection for a relatively short period

of time (6 to 18 months). More recent studies have demonstrated that a toxoid prepared

from the cholera enterotoxin likewise provides only limited protection for a short time.

Although considerable research is now being directed toward developing an oral vaccine, no

solid data exist to indicate that oral vaccines will provide either more effective or more

lasting immunity than the conventional whole-cell vaccines. Rapid advances in treatment

The most remarkable advances have occurred in the treatment of cholera, and have shown

that:

- adequate intravenous fluid therapy should result in the survival of all cholera

patients.

- tetracycline (and other antibiotics) cause a dramatic decrease in both the duration and

volume of intestinal fluid loss and therefore in the volume of fluids required for

treatment.

- oral administration of properly prepared glucose- (or sucrose-) electrolyte solutions

will alone provide adequate treatment for the great majority of cholera patients in all

age groups.

Studies in Bangkok in the late 1950s established two important facts which were

essential to the rapid advances during the 1960s:

- the clear demonstration that the structure of the intestinal mucosal wall is not damaged

during cholera.

- the precise description of the nature of intestinal fluid losses in cholera.

Over the next few years, studies in India and Bangladesh clearly demonstrated that

virtually all patients would survive if they received adequate quantities of the proper

intravenous fluids throughout the two to five day course of cholera. Oral rehydration therapy

Only four years after the demonstration of the effectiveness of antibiotics, another

far more important and radical advance in therapy occurred, which has made it possible to

treat cholera effectively anywhere, with inexpensive, locally available ingredients. This

development was the demonstration, in Dacca and Calcutta, that oral administration of

glucose-electrolyte solutions can effectively restore the intestinal fluid losses in most

cases of cholera. The development of the oral rehydration solution (ORS) was based on the fact that

glucose greatly facilitates sodium absorption by the mammalian intestine. Since the

intestinal wall remains intact during cholera, the mechanism by which glucose enhances

sodium absorption is undisturbed, and the oral administration of glucose-electrolyte

solutions can restore fluid balance even in actively purging cholera patients. WHO: ORS solution A number of glucose-electrolyte solutions have proved to be effective, but the one

which is currently most strongly recommended is the WHO oral rehydration salts solution

(ORS), which consists simply of 3.5 grams of NaCl (table salt), 2.5 grams of NaHC03

(baking soda), 1.5 grams of potassium chloride and 20 grams of glucose (or 40 grams of the

more readily available sucrose or table sugar) per litre of water. This single solution,

when given orally in quantities equal to 1½ times the volume of intestinal fluid losses,

has proved to be effective in both the initial and maintenance treatment of virtually all

cholera patients. Occasionally patients who are already in hypovolemic shock* may still

require an initial intravenous infusion of fluids when first seen by a health worker.

However, most patients can be treated adequately with ORS throughout the course of

cholera. Subsequent studies have demonstrated that ORS is also effective in the treatment of

other acute infectious diarrhoeal illnesses, caused both by other bacterial (e. g.

enterotoxigenic E. coli) and by viruses (e. g. rotavirus). Universal treatment

Now that an effective treatment of acute diarrhoeal disease has been developed, every

effort must be directed towards:

- Ensuring that village health workers everywhere are familiar with the preparation of

ORS, or alternatives using locally available ingredients and measuring techniques.

- Educating the community, especially mothers, in developing countries about the

necessity for beginning oral rehydration as soon as diarrhoea begins and maintaining the

administration of ORS throughout the episode of diarrhoea.

Professor C. C. J. Carpenter, Chairman, Department of Medicine, University Hospitals

of Cleveland, Ohio, USA. * Hypovolemic shock - circulatory failure due to rapid fall in blood volume through

dehydration. Further reading: Pierce N F, Hirschhorn N 1977 Oral fluid - a single weapon against dehydration in

diarrhoea. WHO Chronicle, Vol 31, 87.

|

|

DDOnline

Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 12 February

1983  5 Page 6 7 5 Page 6 7

Control strategies

Although many questions remain about the epidemiology of cholera, there is little

doubt about the most effective control measures. Dhiman Barua

reviews the key strategies. Cholera control can best be achieved through a national CDD programme that ensures

adequate training, proper treatment, community involvement, uninterrupted supplies of ORS,

laboratory and other back-up facilities, regular surveillance, and measures to improve

water supply, excreta disposal, personal hygiene and food safety. The important strategies

for cholera control are described below:

- Early detection of epidemics through continuous surveillance.

- Active case-finding with the help of community elders, religious leaders and

teachers, and through home visits by local health workers reinforced by mobile teams, if

necessary.

- Provision of early and proper treatment of cases. This includes the establishment

of temporary treatment centres if the permanent facilities are not within easy reach, so

infected people travel as little as possible.

- Extremely thorough disinfection of the clothing, utensils, excreta, vomit, and

environs of cholera cases (by boiling, or with disinfectants like lysol, cresol or lime,

as appropriate). The dead bodies of cholera victims should be disposed of with the minimum

of transportation and rites, which can spread the disease.

- Health education, properly carried out, can achieve a great deal, even in the

most desperate situations. All health workers should provide health education while

providing services. All appropriate media should be used and special attention given to

densely populated areas. Simple explanations of factors helping the local spread of

disease and the ways in which the population can help interrupt transmission will secure

community involvement and minimise panic.

Emphasis on personal hygiene (especially hand-washing with soap and water) and on food

and water safety is essential. The necessity for eating only cooked food while still hot

and drinking only safe water (boiled, treated, or collected from a safe source and stored

properly) should be explained. The need to protect all water sources from contamination

must be emphasized; infection is acquired not only by drinking water, but also by bathing

or washing articles at contaminated sources. The population should also be informed about

the dangers of:

- community feasts and gatherings of any kind, particularly funerals, where safe food and

water and proper excreta and waste disposal cannot be assured;

- visiting sick relatives and eating/drinking in the homes of cases;

- contaminated foods e.g. fish and especially shellfish collected from suspect waters,

vegetables irrigated or freshened with sewage-contaminated water.

- Epidemiological investigations to determine how transmission is occurring should

be undertaken by health workers. In most instances, several factors are involved because

of the complex socio-cultural customs of intimate mixing and free exchange of foods/drinks

etc, but there are instances when a common source/vehicle (like a well, shellfish,

vegetables) has been detected by epidemiological investigations, in which case the

outbreak can be quickly controlled by specific interventions.

- Provision of safe water is very important, as the boiling of water is not

practical in many situations. Numerous simple and innovative methods are available for the

supply and treatment of water. Special attention should be paid to the proper protection,

storage and use of water in the home.

- Proper disposal of excreta is vital to protect water sources and the environment.

In the absence of any facilities, burial of all excreta, specially those of cholera cases,

is essential. Refuse disposal by burning, burial, or other methods should be ensured to

prevent fly breeding.

- Chemoprophylaxis i.e. the administration of antimicrobials to healthy persons who

are suspected of carrying V. cholerae and are likely to become sick or spread the

infection is theoretically a sound measure. Yet many countries have experienced that mass

chemoprophylaxis does not produce the desired results mainly because the infection spreads

faster than the time it takes to reach and treat all members of the community. Moreover,

by inducing drug resistance, it deprives the actual cases of an effective drug for their

treatment.

Therefore, chemoprophylaxis only of close contacts in the home of a

case was recommended. Recent experience has shown, however, that in many areas the custom

of intimate mixing of members of the community and of visiting and sharing foods with

extended families makes it difficult to identify close contacts; the recommendation thus

becomes unpractical. Chemoprophylaxis may still be effective in situations where everybody

in the affected community can be treated quickly and simultaneously e.g. a

refugee camp.

- Vaccination is no longer seen as an effective weapon for cholera control because

of its low efficiency in preventing disease and almost total ineffectiveness in preventing

the carrier state. Vaccination is still undertaken in some situations, mainly because it

is demanded by an uninitiated public. This should be countered by proper health education

explaining the limitations of the vaccine and the risks of mass vaccination (e.g.

hepatitis).

Dr Dhiman Barua, Programme for the Control of Diarrhoeal Disease (CDD), WHO, Geneva,

Switzerland. For further reading on this subject contact Dr Barua at the above address.

|

|

DDOnline

Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 12 February

1983  6 Page 7 8 6 Page 7 8

- Community-based health and family planning

Kols A J and Wawer M J Population Reports 1982 X.6 (Series L No 3) pp 79-109

- Oral rehydration therapy: an assessment of mortality effects in rural Egypt.

Tekce B Studies in Family Planning 1982 13:11 pp 315-327.

Involvement of local people, readily available supplies and cultural acceptability are

all reasons why community-based distribution (CBD) of health resources should be

effective. If essential supplies can be obtained nearby there is less difficulty and cost

to poorer families. Communication is easy and items will be more readily accepted if they

are stocked by members of the community who understand how to use them and can explain how

they suit health needs and beliefs. A number of programmes are using CBD for

contraceptives, nutritional supplements, simple treatment for intestinal parasites,

malaria and oral rehydration for diarrhoea. However, operating CBD programmes is demanding. Local depot holders must be trained,

supervised and given regular supplies. Parents need motivation and education to use the

materials correctly. Repeated personal instruction and contact is necessary to remind

people about the availability of supplies and to refresh memories about the right way to

use the facilities. Treatment of acute diarrhoea with oral rehydration therapy (ORT), is an important

technique that can be taught and applied through CBD. However, ORT is time and labour

intensive. Instruction also has to overcome fears and doubts about the method. Some of

these are associated with traditional beliefs and remedies, while others are the result of

resistance and routine practices of doctors and health workers. Several studies of ORT in CBD in Egypt have shown that it can be effective in lowering

the death rate due to diarrhoea in communities. In one study the diarrhoea mortality was

decreased with Oralyte, sugar-salt packets or household fluid programmes.

Egyptian Project,

Strengthening Rural Health Delivery |

Deaths per 1,000 children 1 month to 5 years of

age

in two periods and with various services |

| |

1976-79 |

1980 |

| Oralyte, home distribution |

18.9 |

11.2 |

| Oralyte, commercial source |

19.9 |

16.9 |

| Home prepared sugar-salt |

17.7 |

10.3 |

| Prepackaged sugar-salt, home distribution |

23.4 |

9.3 |

| Control area 1 |

19.4 |

17.3 |

| Control area 2 |

21.5 |

18.8 |

Such improved death rates were not found universally, and in the

Menoufia programme there was no lowering of the diarrhoea death rates in a community in

which mothers were given two Oralyte packets and taught how to use these for their

children in cases of diarrhoea. Apparently in most instances ORT was used too little or

too late. Both these reports emphasize the need for repeated personal instruction and suitable

ongoing support for effective impact from oral rehydration programmes.

- Evaluating the role of health education strategies in the prevention of diarrhoea

and dehydration

Iseley R B Journal of Tropical Pediatrics October 1982 Vol. 28 pp 253-261

Health education can interrupt the lethal diarrhoea-dehydration cycle at three points:

prevention of diarrhoea; management of diarrhoea when it occurs; and the management of

dehydration. However, ways to evaluate the impact of health education strategies are badly

needed. Experienced field workers suspect that community organization is a key element in

bringing about behavioural change and this cannot be achieved through the mass media alone

without local involvement. Village-based health workers are the most effective carriers of

educational messages at household level but they need cooperation from both the mass media

and community leaders in setting up local programmes to deal with diarrhoeal disease

control. Such programmes should include not only environmental improvements but also the

provision of resources for effective oral rehydration therapy, together with the

encouragement of prolonged breastfeeding and better weaning practices. Measuring behavioural change is not easy. This article describes a 'health belief'

model which can be adapted to a traditional culture to provide a framework out of which

evaluation questions can be selected for use. Some form of relevant, local evaluation is

essential if health education services are to be effectively designed to maximize scarce

resources by combining the use of mass media with various types of local interventions to

prevent diarrhoea and dehydration.

|

Journal of Diarrhoeal Diseases Research The International Centre for Diarrhoeal Diseases Research, Bangladesh (ICDDR, B)

(originally known as the Cholera Research Laboratory) is soon launching a Journal of

Diarrhoeal Diseases Research with the encouragement and support of the Canadian

International Development Research Centre (IDRC). The Journal will be a quarterly

publication with an annual index. Contents will include original research articles, short

communications and letters dealing with all aspects of diarrhoeal diseases. There will be special emphasis on the Asian region and each issue will include an

annotated bibliography of current Asian literature on diarrhoeal diseases. The scientific

editors of Diarrhoea Dialogue are both members of the Editorial Advisory

Board and the first issue of the Journal will be fully reviewed in the appropriate issue

of this newsletter. Contributions to the new Journal will be welcomed by its Managing Editor, Mr Md. S. I.

Khan, Journal of Diarrhoeal Diseases Research, lCDDR, B DISC, GPO Box 128, Dhaka 2,

Bangladesh.

|

|

DDOnline

Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 12 February

1983  7 Page 8 7 Page 8

Saving lives

I am the coordinator for the National and Child Health Clinics in this region. We've recently had an extensive epidemic of diarrhoea and dysentery in Tanzania. In

your="dd11.htm">issue No 11, November 1982, I was pleased to read about oral

rehydration therapy (ORT), as we taught it repeatedly to the women who attend our clinic.

Medicine for diarrhoea is almost nil here and ORT was the means to save the lives of many

of the children. I will be particularly interested to read issue No 12 as we are presently treating

cholera. Thankfully, the cases are under control and declining steadily. Sister Katherine Taepke, Makiungu Hospital, P. O. Box 56, Singida, Tanzania.

Local foods Dorothy Francis has written an excellent article on the necessity for continued feeding

during diarrhoea to avert the onset or increase of PEM. Locally available multi-mixes are

rightly commended (Diarrhoea Dialogue 10, page 66). Our Nepal-wide multi-mix (½ roast pulse, ¼ roast grain 'a', ¼ roast grain 'b') and

Kathmandu Valley multi-mix (½ roast soya bean, ¼ roast maize, ¼ roast wheat) - both

called 'Sarbottam Pito' or Super Flour, include soya or other legumes roasted and ground.

Contrary to Dorothy Francis's point of view, we do not find that legumes (roasted

and finely ground by the local traditional process) cause additional digestive

problems.(1) 'Sarbottam Pito' can be used very satisfactorily for young children of five months

upwards, or even three months if mother's milk is genuinely not available. The soya

and cereal mix provides a good combination of amino acids, necessary potassium and other

essential nutrients. I regret that many of the foods listed in Miss Francis's Table 'A' - chicken, rabbit,

beef, lamb (or indeed any meat), egg, arrowroot and often even oils are

scarce and expensive in this developing country. However, our multi-mix provides needed

calories too, and the recipe may be a useful basis for other similar areas to provide

appropriate local diets. Ruth Angove, Nutrition Adviser, UMN Health Services Board, United Mission to Nepal,

P. O. Box 126, Kathmandu, Nepal. (1) Bomgaars Mona R 1976 Undernutrition - Cultural Diagnosis and Treatment of

'Punche'. JAMA, Nov 29 1976, Vol 236, No 22, p. 2513.

Sarbottam Pito 2 parts by volume of one pulse (soya-bean is the best)

1 part each by volume of two cereal grains

- Clean and roast each of the ingredients separately and grind into flour.

- Mix the resulting fine (sifted) flours.

- Store in a closed clean container.

- To prepare the child's feed: boil sufficient water, add the powder, and stir while

boiling briefly. Cool, add a little salt if needed, and use as a weaning or supplementary

food.

|

ORT for adults

Thank you very much for your issues of Diarrhoea Dialogue. I would like to

continue receiving it. I have closely followed your discussions on oral rehydration therapy and enjoy reading

them very much. We in Fiji are recipients of the UNICEF salts packages, which have gone a

long way in controlling our diarrhoeal diseases. But one issue concerning these packages

really concerns me. I have often seen my fellow colleagues issuing these packages to adults suffering from

diarrhoeal diseases. I should be very grateful if in a future issue of Diarrhoea Dialogue you could

discuss the following:

- Should adults be prescribed these UNICEF packages?

- If no, are there any special adult preparations of salts packages?

- Will an early replacement therapy be of any use to adults?

Please accept my appreciation for the task you are undertaking on educating and keeping

us abreast (particularly those of us from developing countries) of developments in the

world of diarrhoea. Yours in health, Dr A W Khan, Medical Officer, Tavua Hospital, Tavua, Fiji Islands, South Pacific.

Editors' note:

|

Spreading the ORT message to everyone. This letter demonstrates the need to spread the ORT message more widely and more

clearly. Anyone who has diarrhoea needs early oral rehydration therapy, regardless of age

or size. Because dangerous dehydration occurs so quickly in small children, they must be

the first to benefit from the special UNICEF packets. The formula also works for adults

but they can, as an alternative, be advised to drink large amounts of water to which

glucose or sugar and a little salt has been added.

|

If packets are not available, children may also be given similar

home made oral rehydration mixtures as described in earlier issues of Diarrhoea Dialogue.

Not more than a pinch of salt should be used to a cupful of water or a teaspoon to a

litre; too much salt is not good for children.

|

Scientific editors Dr Katherine Elliott and Dr William Cutting

Executive editor Denise Ayres Editorial advisory group

Professor David Candy (UK)

Dr I Dogramaci (Turkey)

Professor Richard Feachem (UK)

Dr Michael Gracey (Australia)

Dr Norbert Hirschhorn (USA)

Dr D Mahalanabis (India)

Professor Leonardo Mata (Costa Rica)

Dr Mujibur Rahaman (Bangladesh)

Dr Jon Rohde (USA)

Ms E O Sullesta (Philippines)

Professor Andrew Tomkins (UK)

Dr Paul Vesin (France)

Dr M K Were (Kenya) With support from WHO, UNDP, UNICEF GTZ and SIDA

|

Issue no. 12 February 1983

Page Navigation

This edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online is produced by Rehydration Project. Dialogue on Diarrhoea was published four times a year in English, Chinese, French, Portuguese, Spanish, Tamil,

English/Urdu and Vietnamese and reached more than a quarter of a million readers worldwide. The English edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea was produced and distributed by Healthlink Worldwide. Healthlink Worldwide is committed to strengthening primary health care and

community-based rehabilitation in the South by maximising the use and impact

of information, providing training and resources, and actively supporting

the capacity building of partner organisations. - ISSN 0950-0235 Reproducing articles

Healthlink Worldwide encourages the reproduction of

articles in this newsletter for non-profit making and educational uses. Please

clearly credit Healthlink Worldwide as the source and, if possible, send us a copy of any uses made of the material.

|

updated: 23 August, 2019

updated: 23 August, 2019

|