|

| |

Issue no. 29 - June 1987

pdf

version of this

Issue version of this

Issue

|

There is much information in this issue that is valuable

and useful. Online readers are reminded, however, that treatment guidelines and health

care practices change over time. If you are in doubt, please refer to

WHO's up-to-date Dehydration Treatment

Plans.

|

Pages 1-8 Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online Issue 29 - June 1987

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 29 June 1987  Page 1 2

Page 1 2

Training the trainers

While communities mostly possess good sense and will co-operate in behaviour change

when they are shown that this is to their advantage, it may be more difficult to persuade

some health professionals that they will receive any personal advantage from the promotion

of oral rehydration therapy. Yet their attitudes are crucial if the idea of drinking as

the appropriate response to diarrhoea is to become successfully imbedded in the minds of

all ordinary people. Health professionals must themselves be convinced that oral

rehydration works satisfactorily enough to be considered the correct scientific response. Need for new attitudes

|

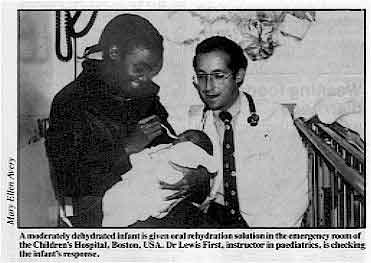

A moderately dehydrated infant is given oral

rehydration solution in the emergency room of the Children's Hospital, Boston, USA. Dr

Lewis First, instructor in paediatrics, is checking the infant's response.

Medical education has tended to emphasise the responsibility of doctors to intervene,

to apply their special knowledge in a way that adds, often dramatically, to their status.

As the possibilities of dramatic intervention have increased, thanks to the growth in

scientific knowledge over the last 50 years, so has the seductiveness of advanced medical

technologies.

|

To set up an intravenous drip or to prescribe a new 'miracle' drug has more appeal than

recommending the giving of a simple drink.

Doctors have spent years learning the mysteries of medicine, but now in diarrhoea, they

are being asked to co-operate in demystification of medical technology. They are being

asked to recommend a remedy which any family can learn to carry out at home, given simple

instructions and simple ingredients. In the case of oral rehydration programmes for

treatment of acute diarrhoea, whatever the causative agent, the attitude of influential

medical leaders, especially the paediatricians, is crucial. They are the ones who teach

the medical students and order the treatment procedures in hospitals and health centres.

Only when they are convinced will ORT be fully accepted at all levels as the treatment of

choice. Learning by doing

To achieve this goal, the scientific basis of ORT needs to be continually stressed.

Theory, however, is of little use without practice, and 'learning by doing' is an

important part of the detraining and retraining process. Oral rehydration, properly

carried out, is dramatic in its effects; anyone who has personal experience of orally

rehydrating a severely dehydrated child cannot fail to be convinced of its value. Nothing

in the way of information can replace that actual experience. In thinking about training

at all levels, it is useful to remember the adage:

What I hear, I forget

What I see, I remember - but

What I do, I know.

This issue of DD highlights some recent initiatives that have been taken to

improve medical training in management of diarrhoeal diseases, and also includes practical

guidelines for evaluating the effectiveness of training programmes. KME and WAMC

|

In this issue . . .

- Improving medical training

- Children as educators

- Evaluating training

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 29 June 1987  1 Page 2 3 1 Page 2 3

India: ORT survey To find out more about current practices and beliefs concerning diarrhoeal disease and

its treatment, a questionnaire was sent to 200,000 doctors throughout India. The following

is a summary of findings based on the 15,000 replies received (7.5 per cent). The majority

were returned by modern allopathic practitioners, although about one-quarter were returned

by doctors from indigenous and other systems of medical care. All respondents had received

the WHO/UNICEF Joint Statement on ORT. Two-thirds claimed to use ORS in their practice. A

similar percentage believed that mothers can manage most diarrhoeal cases at home and 76

per cent claimed that mothers already give fluid to their children during diarrhoea.

Three-quarters of respondents stated that they teach mothers how to make ORS as part of

their advice. However, while over 70 per cent cited correct quantities of salt and sugar

for mixing home-made ORS, more than a quarter suggested formulas scientifically considered

to be unsafe, indicating an urgent need for further education and standardisation of

formulations. Feeding The overwhelming majority of doctors who replied (94 per cent) were aware that repeated

diarrhoeal episodes contribute to malnutrition, but 60 per cent recommended less food to

be given during diarrhoea, and the same number recommend a change from regular diet to

liquids and soft foods. Almost one-third recommend continuation of breastfeeding but

stoppage of all other foods. Clearly more information and teaching is needed about correct

nutritional support of children with diarrhoeal disease. Drug therapy Thirty-seven per cent of all doctors claimed anti-diarrhoeal preparations are

absolutely essential in all cases of diarrhoea, and another 55 per cent felt they were

sometimes essential. This use of anti-diarrhoeals by nearly all respondents demonstrates

the extent of the problem, for these drugs generally divert attention from oral

rehydration and are also too expensive for most families. Antibiotics are used regularly

by 40 per cent of doctors, although most claimed that they use them only in selected

cases. Intravenous (IV) fluids are used by 80 per cent of doctors in less than 15 per cent

of cases. WHO and Indian experts have, however, estimated that only 1 per cent of all

cases need IV fluids. While many Indian practitioners are clearly conversant with the ORT message and claim

to be using it in their practices, important efforts are needed to:

- promote use of standard and effective fluids in the home for early treatment of

diarrhoea;

- reduce dependence on, belief in and use of anti-diarrhoeals;

- influence more judicious and selective use of antibiotics; and

- improve nutritional management of the child with diarrhoea.

Rolf C. Carriere, Chief, Health and Nutrition, UNICEF, Regional Office for

South-Central Asia, 73 Lodi Estate, New Delhi 110 003, India. Editor's note: When, as in this survey. only a small percentage of questionnaires are returned and

analysed, further studies may need to be carried out to determine the actual practices of

mothers and physicians. WHO is currently developing protocols to measure practices and

effective case management in the home and in health facilities. Weaning foods and diarrhoea In many parts of Eastern and Southern Africa porridges are made by fermentation of a

cereal 'mash' with various species of lactobacilli. Milk or milk products are not used in

the process, and these porridges are often prepared by people who do not have access to,

or cannot afford, milk. (After a day or so the porridge becomes sour and the pH falls to

around three. No alcohol is formed.) Sour porridges are prepared by a wide range of

methods from sorghum, millet, maize or a mixture of these cereals. In some countries, for

example Lesotho and parts of Kenya, these porridges are popular weaning foods for young

children. In other countries sour porridges are popular among adults but are not given to

young children, although this may not have been the case in the past. There is considerable evidence which suggests that fermenting with lactobacilli and the

resulting low pH of sour porridges due to lactic acid formation significantly reduces the

chances of contamination with coliform bacteria likely to cause diarrhoea. (Such an effect

is of course widely recognised with sour milk products but the literature on the lactic

(as opposed to the alcoholic) fermentation of cereals is not very extensive.) Souring of

cereal porridges may therefore be an appropriate technology facilitating the frequent

feeding of young children. A large batch of porridge could be prepared in advance and

safely stored until needed for child feeding. This would be more practical than advocating

cooking fresh weaning porridge three times a day when constraints on women's time,

availability of fuel, washing facilities and utensils are considered. Some evidence suggests that lactic fermentation reduces the viscosity of the porridge

thus making easier the preparation of energy dense porridges. Fermentation also increases

the digestibility of sorghum protein and bio-availability of many vitamins and minerals.

Mothers have said that sick and anorexic children like the taste of the sour porridge and

that this encourages them to eat. People in many countries also believe that sour sorghum

or millet porridge stimulates the production of breastmilk. Given this long list of

apparent advantages it is perhaps surprising that health workers in the region have not

been more keen to promote the use of sour porridges in young child feeding. Some health

staff claim that they cause indigestion and heartburn (although mothers that I have talked

to do not agree) and that they are difficult to mix with other foods. Fashion, and the

increasing tendency towards western ways of doing things, and the fact that such

traditional foods are rarely discussed when health workers are trained may be more

important reasons which discourage use of such porridges. I am collecting information to help clarify the advantages and disadvantages of this

technology with respect to young child feeding, and would welcome comments from DD readers. David Alnwick, Regional Advisor, Household Food-Security and Nutrition,

UNICEF, Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Office, Nairobi, Kenya.

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 29 June 1987  2 Page 3 4 2 Page 3 4

Improving medical education

Medical school training determines the future practice of doctors regarding

management of diarrhoea. Perla Santos Ocampo reports on

initiatives in the Philippines. The crucial role of the physician in supporting ORT cannot be too highly

emphasised.

The physician is seen by other health workers as the leader in health care delivery. His

practices, based on medical school training, are imitated. Unfortunately, the need to

impress patients and the desire to apply what has been learned in medical school may mean

that he will ignore a simple intervention, such as ORT, even though this is known to be

sound, scientifically based and effective. Instead, drug and IV therapy may be used for

acute diarrhoeas, and this is reinforced by public demand. Need for curricula changes Changes in curricula are thus needed to emphasise the role of ORT in the management of

acute diarrhoea. In the Philippines, the Task Force on Paediatric Education (under the

Association of Philippine Medical Colleges), decided it was necessary to focus on low-cost

highly effective health technologies such as oral rehydration in diarrhoea, and

immunisation, in the competency-based paediatrics curriculum. Medical school commitment The first step was to ensure the involvement of both the Dean and Chairman of the

Department of Paediatrics of all 26 medical schools in the Philippines in a two day

workshop. The commitment of the deans 'to offer curricular programmes emphasising these

effective health technologies and to give the necessary assistance and support to promote

the teaching of these effective health technologies to undergraduate medical students,

including the provision of community-based outreach programmes and 'hands-on' (practical

and personal) experience was obtained. The Task Force then formulated learning objectives

for teaching about diarrhoeal diseases in medical schools. Learning objectives and training methods The learning objectives are orientated towards practical skills and relate to the

community. As far as possible, teaching is to be conducted in different locations: in the

community, ambulatory care areas, wards or ORT corners. Adopting learning objectives is

not enough. Most important are the teaching methods used to communicate to students the

superiority and usefulness of ORT, and the knowledge and skills needed for its correct

use. Other teaching methods than lectures, such as role-play, group discussions,

demonstrations, direct patient interaction, pretests, post-tests, working tests, and case

presentations are encouraged.

|

In Egypt, physician involvement in teaching mothers has

contributed to greater acceptance and use of ORT. The whole clinical team, including physicians, residents, interns, nurses, dietitians

and pharmacists, is to be involved in teaching. Teaching about diarrhoeal diseases will be

integrated with other disciplines, including community and family medicine. Modules are

now being developed by the various medical schools to emphasise ORT and other strategies

in the control of diarrhoeal diseases.

|

'Hands-on' experience Opportunity for hands-on experience is crucial: students must do and see for themselves

the improvement brought about in just a few hours using ORT. In a preliminary survey,

medical students exposed to an ORT corner in the University of the Philippines were

impressed with the efficacy, safety, simplicity, and cost-effectiveness of oral

rehydration. There is no substitute for hands-on experience in converting non-believers to

ardent exponents of ORT. It is most important that medical students learn about the value

of ORT and other proper diarrhoeal disease control measures in order to produce physicians

whose diarrhoea management practices are safe, effective and appropriate and which place

due emphasis on ORT. Physicians as trendsetters Medical opposition has been recognised as a significant obstacle to use of ORT in

diarrhoea management. If highly respected physicians, in their capacity as opinion leaders

or trendsetters in the community, use ORT in their practices, this can effectively add

prestige to ORT as the treatment of choice for acute diarrhoea. Perla D. Santos Ocampo, MD, Professor of Paediatrics, University of the Philippines,

Chairman, Task Force on Paediatric Education, Association of Philippine Medical Colleges,

Manila, Philippines. Professor Santos Ocampo is also President Elect of the International

Paediatrics Association.

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 29 June 1987  3 Page 4 5 3 Page 4 5

Recent initiatives In August 1985, medical educators met in Geneva to seek areas where current

medical education about diarrhoea might be improved. Robert Northrup

and Roberto Unda report. Why do so many physicians resist using ORT, even new graduates from medical school?

This problem is a challenge for diarrhoeal disease control programmes in many countries

since physician behaviour strongly influences the behaviour of other health workers and

mothers. More is involved than just the choice between intravenous or oral rehydration:

- physicians often use unnecessary anti-diarrhoeal drugs and antibiotics to treat acute

watery diarrhoea;

- they often recommend 'resting the gut' during diarrhoea rather than continuing feeding;

- they often communicate poorly with mothers, so that mothers leave the clinic without a

clear understanding of how to prepare and administer oral rehydration solution, or how to

detect signs of dehydration; and

- they often direct and supervise health centre and community diarrhoea programmes, but do

so poorly.

Many factors influence the behaviour of doctors. These range from drug promotion by

pharmaceutical companies to Ministry drug buying policies, from the greater profitability

of drugs over ORS packets to pressure from patients to use intravenous treatment. However,

all agree that the doctor's basic medical education about diarrhoea is a critical

influence on subsequent behaviour. Teaching deficiencies A number of aspects of medical teaching support or discourage ORT and appropriate CDD

behaviours in the graduate physician. These are presented as a kind of checklist for

medical schools about their diarrhoea teaching.

- Does the teaching hospital have a diarrhoea rehydration unit which emphasises oral

rehydration and continued feeding for diarrhoea patients? Is there an oral rehydration

'corner' in the paediatric outpatient or ambulatory clinic?

- What percentage of mild and moderately dehydrated patients are treated with ORS? With

intravenous fluids? With anti-diarrhoeal drugs? With antibiotics?

- What percentage of mothers of diarrhoea patients know when they leave the clinic how to

prepare and administer ORS correctly, how to feed their child during diarrhoea and

afterwards, and how to check for dehydration?

- How many diarrhoea patients has each medical student managed personally by graduation?

How many cases has he orally rehydrated with his own hands? How many children with

diarrhoea has he fed himself?

- How many individual mothers has each medical student taught about ORT and diarrhoea

prevention? How many groups of mothers? Does the school check the student's teaching by

interviewing the mothers to see if they have actually learned?

- Does the medical school curriculum include activities to produce skills in teaching

about ORT and feeding during diarrhoea, knowledge about the national diarrhoea control

programme, skills in designing and carrying out a community survey about effective use of

ORT by mothers, and skills in planning, implementing, and evaluating a project in

diarrhoea control for a community?

Changing the curriculum Where in the curriculum are good learning experiences about diarrhoea and ORT most

critical in affecting future behaviour? The final clinical rotations, where the student's

see their paediatric professors treating patients correctly or incorrectly, and where they

treat diarrhoea cases themselves, are doubtless much more important than the lectures or

laboratory sessions of earlier years, which are usually quickly forgotten. To make clinical teaching most effective, the group recommended the following:

- Every medical school should have a Diarrhoea Training Unit (DTU)

As described

by WHO (1), a DTU is primarily a set of clinical teaching activities rather than a

particular clinic room or ward. Thus, students learn from direct experience how to assess

dehydration. They rehydrate mildly or moderately dehydrated patients, giving oral fluid to

the child themselves, and learning effective methods to teach mothers ORT for home use.

In the emergency room, the ambulatory paediatric clinic, and the inpatient ward, the

DTU functions to establish treatment policies and monitor care given. Students passing

through each of these areas, as part of the diarrhoea curriculum, learn from direct

experience the skills of inserting IVs and nasogastric tubes for severely dehydrated

patients, of managing dysentery and chronic diarrhoea, and of linking feeding and

nutrition to diarrhoea management. In a well-run DTU the students' professors become role

models practising correct diarrhoea management with emphasis on ORT. Their example

motivates students to manage diarrhoea patients in the same way.

- Ten diarrhoea patients before graduation

Getting enough experience is

essential. One case is not enough to teach the necessary skills in diarrhoea management.

It was suggested that a minimum of ten cases of paediatric diarrhoea must be managed

properly by every medical student before he can graduate. The need for a supervisor's

signature in the student's logbook, and the use of an objective supervisor's checklist and

interviews with mothers will help to ensure that treatment and education of mothers are

carried out properly and effectively.

- Skills in management, supervision and community diarrhoea control

Physicians

are more than diarrhoea clinicians. Medical school education should also prepare students

for their wider future responsibilities. Even new graduates are often made responsible for

planning, implementing and evaluating community diarrhoea programmes. They become trainers

of other health workers and community groups. They supervise other health workers in

diarrhoea treatment, and community level diarrhoea prevention and control activities.

Adequate direct experience during training, often in the community and in health centres,

is necessary to give students the skills needed to carry out these activities. Focusing on

diarrhoea can make these experiences more measurable and meaningful to students.

- Skills and problem-solving

While knowledge is certainly needed as a basis for

most of these skills, knowledge-oriented activities like lectures are often

over-emphasised in medical school curricula. First priority should be given to activities

and practical skills. Faced with a clinical or community problem to solve, medical

students will be motivated to seek the necessary knowledge themselves.

- Clinical learning modules

As a follow up to this meeting, PRITECH (under

contract to WHO/CDD, and with additional support from USAID), is producing clinical

learning modules for use in medical schools. The initial ones will be related to clinical

teaching in the DTU. Modules for community teaching will be developed subsequently. Each

will include detailed educational objectives; an instructor's guide for carrying out the

activities in the module; special attachments and readings for the instructor; and student

handouts and readings. A bank of examination questions will provide pre-tests, post-tests

and working tests for each module as well as final examinations. Special supervisory

checklists have been prepared to improve clinical supervision and ensure that skills have

been acquired by the student. A general instructor's manual will give sample schedules for

the activities, provide general instruction on how to run the different types of learning

activities, and describe how to use the exam bank. The types of learning activities used

include readings; simulated cases; group discussion; debates; role-playing; demonstration;

clinical rounds; direct patient care.

Modules being prepared for the clinical component are:

- effective doctor-mother interaction;

- clinical management of diarrhoea cases with no or some dehydration;

- clinical management of dysentery, chronic diarrhoea, and diarrhoea accompanying other

diseases;

- nutrition and feeding in diarrhoea;

- assessment and monitoring of clinical care.

1. Diarrhoea Training Unit Director's Guide, WHO, CDD/SER/ 86.1, 1986.

Dr Robert S. Northrup and Roberto F. Unda, PRITECH, Medical Education in Diarrhoea

Control (MEDIAC) Project, Management Sciences for Health, 1655 N Fort Meyer Drive,

Arlington, VA 22209, U.S.A.

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 29 June 1987  4 Page 5 6 4 Page 5 6

An American perspective Mary Ellen Avery and John Snyder

report on acceptance and use of oral rehydration therapy in the United States. Where it has been implemented in developing countries, oral rehydration therapy (ORT)

has been shown to be safe, effective and inexpensive. In the past in the United States,

mild diarrhoea was treated with avoidance of solid foods and substitution of 'clear

liquids'. We now know that these 'clear liquids': tea, carbonated beverages, broths and

fruit juices can be appropriate fluids to prevent dehydration and maintain hydration, but

are not appropriate for treatment of clinical dehydration. At least seven commercially manufactured oral glucose-electrolyte solutions are

available which approximate the WHO formulation. Most have slightly less sodium, about 50

to 70 mEq, but have proved to be effective maintenance and rehydration solutions in

controlled trials in infants and young children. These ready-made solutions are available

at most supermarkets and are sold without prescription. Packets of salts and glucose to

mix with water are also available without prescription, but are less widely used than the

more convenient (but also more expensive) ready-to-use solutions. The frequency, volume,

and effectiveness of packet use has not been reported in population-based studies, but is

felt to be growing. However, expense may limit use of commercial rehydration drinks among

the poorer socio-economic population groups who could most benefit from them. 'Hands on' experience of ORT At the Children's Hospital, Boston, where mostly mild to moderate dehydration is seen,

treatment in the out-patient department is started with oral rehydration, following the

WHO/UNICEF guidelines. A programme of instruction and 'hands-on' experience with ORT has

been established. Major reasons for preferring oral rehydration are that it is safer than

intravenous therapy, it often avoids hospital admissions, and it provides the opportunity

to educate parents about its early use at home. Furthermore, we are anxious that our

students and housestaff gain first-hand experience with ORT so that they will see its

effectiveness and at least will be prepared to challenge the old belief that intravenous

rehydration is somehow preferable. Without 'hands-on' experience it is often difficult to

convince those who have used intravenous rehydration successfully for years that a therapy

so simple and so inexpensive is indeed better. IV used only rarely Intravenous solutions are given only in unusual cases, such as very young infants with

diarrhoea in whom we suspect sepsis and want to start intravenous antibiotics pending

results of blood, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid cultures, or children with severe

dehydration, shock or coma. Even then, as soon as the child can drink, maintenance oral

hydration by mouth is given, and more calories are gradually introduced by eight to 24

hours in patients under the age of six months, and earlier in older children. ORT for burns Oral rehydration can also be a life-saving measure in other situations. Immediately

after an extensive burn, a child may still be responsive enough to take oral fluids, which

will help to lessen the net loss of fluids caused through blisters and loss of skin. At the Boston Children's Hospital, giving fluids by mouth is endorsed as the best means

of preventing dehydration, and oral rehydration as the best therapy in the face of fluid

losses. We expect continued acceptance of these measures and a reduction of dependence on

intravenous therapy in the future. Mary Ellen Avery, Thomas Morgan Rotch Professor of Paediatrics and John Snyder,

Assistant Professor of Paediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 29 June 1987  5 Page 6 7 5 Page 6 7

Evaluation of training Birger Forsberg describes several methods for evaluating

the impact of training on the practices of health workers. Training in programmes for the control of diarrhoeal diseases (CDD) is very much

oriented towards changing health workers' performance in supervisory activities and their

behaviour in the treatment of diarrhoea. It is becoming increasingly important to evaluate

this aspect as countries accelerate their programme activities. Some countries have

started to develop methods for evaluating the impact of training on the practices of

health workers. Follow-up In the United Republic of Tanzania, for example, a series of clinical management

workshops was held in 1986. Supervisory visits are now being made to participants, six to

12 months after the training, to assess how they are applying the skills taught at the

workshops. As one of the objectives of the training was to teach participants how to

organise diarrhoea training sessions, this area is given special attention during the

follow-up visits. The trainees are given the opportunity to explain their problems and the

assistance they need to successfully promote proper diarrhoea management in their

hospitals. This type of follow-up is appropriate when a training programme is focused on a

small group of persons who have a major responsibility in the CDD programme. It is not

feasible for the evaluation of large-scale training activities. Nepal provides an example of how extensive programmes can be evaluated. The country is

training health workers in a new regionally phased programme. During a CDD programme

review in 1986, the practices and skills in the treatment of diarrhoea of a random

selection of health workers were assessed (Table 1). Records showed that children treated

at health posts in districts where the staff had been trained were significantly more

likely to receive ORS than those in 'untrained' districts. There was little difference in

the use of antibiotics between the two groups. Written guidelines for diarrhoea treatment

were available more than twice as often in facilities with trained personnel.

|

Table 1.

Availability of written guidelines

and frequency of treatment of diarrhoea with ORS and antibiotics at health posts, Nepal |

| |

With trained staff |

With untrained staff |

| No. |

Per cent |

No. |

Per cent |

| Health posts surveyed |

13 |

- |

13 |

- |

| Posts with treatment guidelines |

7 |

54 |

3 |

23 |

| Diarrhoea cases in under-fives |

219 |

- |

103 |

- |

| Cases treated with ORS |

156 |

71 |

48 |

47 |

| Cases treated with antibiotics |

178 |

81 |

96 |

93 |

Comparing trained and untrained health workers Interestingly, interviews with health workers did not reveal any differences between

trained and untrained health post workers in knowledge of how to assess and treat

diarrhoea, primarily because the untrained health workers were fairly familiar with these

skills already. This suggests that the training has been partially successful in changing

the practices of the health workers with regard to the use of ORS. Further efforts must

now be made during training to discourage the use of antibiotics. Checking records Another example can be taken from Sudan. A rural health training programme was

evaluated by a review of daily attendance records at different health stations. This

involved counting total numbers of visits, diarrhoea and dysentery cases, and cases given

antibiotics, ORS, or both. Records were checked before training in ORT, and at intervals

of one, six and 18 months after training. The results are shown in Table 2.

|

Table 2.

Diarrhoea and treatment

with ORS and sulphonamides, Sudan |

| |

No. of cases |

ORS |

Sulphonamides |

| |

% |

% |

| Before introduction of ORT |

1140 |

8 |

76 |

| 1 month after training workshops |

698 |

64 |

45 |

| 6 months after training workshops |

1981 |

59 |

38 |

| 18 months after training workshops |

4060 |

72 |

22 |

The training appears to have had a definite impact on the behaviour of

the health workers; ORS was prescribed much more often and antibiotics less often than

before the workshops. Evaluation is an important part of training programmes. These examples illustrate some

ways of evaluating the impact of training on the actual performance of health personnel:

- follow-up visits including discussions with trainees;

- interviews, observation and comparison of trained and untrained health workers; and

- checking and comparison of hospital records before and after training.

Health staff in charge of CDD programmes and Diarrhoea Treatment Units (DTUs) could

consider including such methods in their training programmes. Birger Forsberg, MD, Evaluation Officer, CDD Programme, WHO, 1211 Geneva 27,

Switzerland.

DD would like to hear from readers about their own experiences with evaluation of

training.

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 29 June 1987  6 Page 7 8 6 Page 7 8

Children can be teachers Mark Swai describes how children, taught about ORT at

school, can help to reinforce learning by mothers. In the Moshi district of Tanzania, 79 children from the older classes of two randomly

selected primary schools were given questionnaires to answer, about diarrhoeal disease and

how to treat it. This was followed by two activity lessons about diarrhoea which included

making visual aids and participating in making oral rehydration solution with sugar, salt

and water. The children were also given 'homework' which involved showing their parents

the visual aids and discussing with them what they had learnt at school. What mothers already knew The children's mothers were asked questions before and after the children did their ORT

'homework'. There was a wide variation in what the mothers knew already about diarrhoeal

disease. Some thought it was 'not serious', while in one tribal group it was described as

'enemy number one'. Many realised that it could lead to death. Almost equal numbers said

that they would take a child with diarrhoea to hospital, as said they would take a child

to a traditional healer. About three quarters of the mothers said they would continue

breastfeeding during diarrhoea and an even larger number said they would continue giving

other foods. Twenty-one per cent of the mothers said they would restrict fluids during

diarrhoea, and almost all of these were from the tribe who described the condition as

'enemy number one'. Nearly all mothers had heard of oral rehydration therapy (ORT) for diarrhoeal disease.

Over 80 per cent had seen it used in MCH clinics and almost 80 per cent had actually used

it themselves. Despite this widespread general knowledge about ORT, very few knew about

ORT in any detail. Relatively few could prepare a solution correctly with sugar and salt,

and the majority made it too concentrated. When asked how they would give OR fluid, many

mothers said 'three teaspoonfuls three times a day', and 22 per cent said that ORT

'prevents diarrhoea', implying that they did not understand the basic principles of the

therapy. After their children had discussed the topics with them, many mothers were able to

point out the features of dehydration much more accurately. The number who recognised

reduction in urine and a dry mouth as important signs of dehydration doubled. The number

who knew a sunken fontanelle and sunken eyes to be signs of dehydration also increased,

from 71 and 81 per cent respectively, to virtually all mothers. Over 40 per cent of

mothers showed improved understanding of the role of ORT in treatment, and, most

important, the number who could make up a correct solution increased from 13 to 65 per

cent. (Unfortunately this still leaves 35 per cent who could not make up a safe and

satisfactory solution.) Schools for health education In many countries there are far more primary schools than there are health facilities.

For example, in the Kilimanjaro region of Tanzania, with a population of 1.2 million,

there are only 189 health facilities but 703 primary schools. In the Kisumu district of

Kenya the ratio is even more striking, with only 16 health facilities and 295 primary

schools. If health messages, for example about the effective use of ORT, are to reach

homes in such circumstances, schools and school children are an important resource. Dr Mark E. Swai, KCMC Hospital, P. 0. Box 3010, Moshi, Tanzania.

|

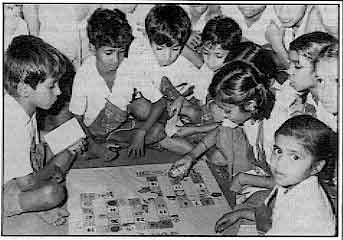

A diarrhoea game

|

Learning

is more agreeable, interesting, effective and lasting for school children when it is done

through games. With this in mind, a health education game on diarrhoea has been developed

for school children in Bombay. The game is played on a board. Any number of children can

play. |

Each child throws the dice in turn. If they land on a good health habits square, they

can move again, for 'bad' practices, the player has to move back. The first person to

reach the final square 'healthy home' is the winner. The children enjoy the game very

much.

This game was designed to teach and encourage school children to concern themselves

with their health and that of their younger brothers and sisters. The children learn

simple preventive and promotive health measures appropriate for their communities.

They pass on what they learn to other children and to their families. In the game causes

of diarrhoea, symptoms, signs, treatment and advice are covered in simple

rhymes.

Dr Daksha D Pandit and Dr N P Pai, Preventive and Social Medicine Dept,

Topiwala National Medical College, Bombay 400 008, India.

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 29 June 1987  7 Page 8 7 Page 8

Oral rehydration and the medical profession Oral rehydration therapy (ORT) has gained wide acceptance in the Third World, thanks to

the massive promotional support given by the international agencies like WHO and UNICEF.

The paediatric professionals in developing countries are believed to have rallied round

the ORT bandwagon to promote its acceptance. Unfortunately, certain disturbing signs have

either not been perceived or are considered too trivial to warrant remedial measures. In India, medical students learn pharmacology and therapeutics at the beginning of

their clinical studies. What they learn will certainly influence their attitudes to

management of diseases. One of the most popular Indian text books 'Pharmacology and

Therapeutics' discusses scientific management of diarrhoea thus: 'symptomatic and

supportive therapy includes control of diarrhoea with anti-diarrhoeal agents and

correction of dehydration and electrolyte disturbances. The latter is the most important

aspect of treatment in severe diarrhoea'. However, the book next presents an

elaborate discussion of the drugs used in the symptomatic treatment of diarrhoea under

three headings. (1) Gastrointestinal protectives and adsorbants, (2) Drugs affecting

intestinal motility and (3) Miscellaneous agents. Nearly three pages are devoted to a fairly thorough discussion on the use of bismuth,

prepared chalk, light kaolin, pectin, activated wood charcoal, codeine,

diphenoxylate,

loperamide and lactobacillus acidophilus. There is not a word on oral rehydration in the

chapter on diarrhoea. One cannot help feeling that thousands of medical students in India

start with their 'basics' wrong in the management of diarrhoea. More shocking however is the professional practice of the paediatricians. I made a

critical evaluation of the management of diarrhoea in a leading teaching hospital of our

country, where over 2,000 children are admitted annually for diarrhoea. A survey of a

hundred randomly selected case records revealed the following practices. Most of the

children admitted had only mild or moderate dehydration. The majority of children with

mild or moderate dehydration received intravenous fluids on admission. Oral rehydration

solution was given as a supplement to IV fluids. Almost all children (92 per cent), with

acute or chronic diarrhoeas, received a combination of pectin and kaolin. No child with

vomiting ever escaped an antiemetic preparation like promethazine. Stool tests were

restricted at best to an occasional microscopic examination; stool cultures were seldom

sought. Case records abound with combinations like ampicillin, metronidazole,

gentamicin,

etc. Oral preparations of lactobacillus acidophilus were frequently administered to

children with all types of diarrhoea. What is most disturbing is that the institution is a leading centre of both

undergraduate and postgraduate training in paediatrics. The senior members of the faculty

have all been exposed many times to the modern trends of management of diarrhoeas and in

turn are vocal exponents of oral rehydration therapy and rational management of diarrhoea.

Somehow, at the moment of reckoning, old habits prevail over new concepts. I have no

reason to believe that the example is an isolated one, peculiar to India. It is not

unusual to overhear young trainee paediatricians saying that 'ORT' is good public

relations, while IV is excellent private management. Unless paediatric professionals in

the Third World change their practices, the whole concept of rational management of

diarrhoea and ORT may lose popular appeal. Third World mothers will place more faith in

what doctors practice, than in what they preach. Dr C R Soman; Professor of Nutrition, Medical College, Trivandrum, India.

|

News about DD

- Tamil edition . . .

The Rural Unit for Health and Social Affairs at

the Christian Medical College in India has produced a Tamil translation of="dd19.htm">issue 19 of Dialogue on Diarrhoea. Issue 19 focused

on ORT and readers who would like to obtain copies in the Tamil language should write to Dr

R Abel, RUHSA, Christian Medical College and Hospital, P.O. Box 632209, North Arcot

District, Tamil Nadu, India.

- Poster competition . . .

On="#page7">page 7 of this

issue we describe the important role which children can play in educating their parents

and brothers and sisters about better management of diarrhoeal diseases. Following this

theme, the Editors are pleased to announce a poster competition for children. Prizes will

be given for the best entries, and children can enter individually or as a school. We hope

that teachers will find this project a helpful way of getting children to think about

better health practices. For further details about the competition and how to enter,

please see the form enclosed in this issue.

- In the next issue . . .

In many countries women are responsible for

fetching, carrying and storing water for family use. Hygiene and sanitation practices are

also largely dependent on women. DD 30 returns o the

theme of water and sanitation, focusing in particular on the role of women.

|

Scientific editors Dr Katherine Elliott and Dr William Cutting

Managing editor Kathy Attawell

Editorial advisory group

Professor J Assi Adou (Ivory Coast)

Professor A G Billoo (Pakistan)

Professor David Candy (UK)

Professor Richard Feachem (UK)

Dr Shanti Ghosh (India)

Dr Michael Gracey (Australia)

Dr Norbert Hirschhorn (USA)

Dr Claudio Lanata (Peru)

Professor Leonardo Mata (Costa Rica)

Dr Jon Rohde (USA)

Ms E O Sullesta (Philippines)

Professor Andrew Tomkins (UK)

Dr Paul Vesin (France)

Dr M K Were (Kenya) With support from AID (USA), ODA (UK), UNICEF, WHO Publishing partners

BRAC (Bangladesh)

CMAI (India)

CMU (China)

Grupo CID (USA)

HLMC (Nepal)

lmajics (Pakistan)

ORANA (Senegal)

RUHSA (India)

Consultants at University Eduardo Mondlane (Mozambique)

|

Issue no. 29 June 1987

Page Navigation

This edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online is produced by Rehydration Project. Dialogue on Diarrhoea was published four times a year in English, Chinese, French, Portuguese, Spanish, Tamil,

English/Urdu and Vietnamese and reached more than a quarter of a million readers worldwide. The English edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea was produced and distributed by Healthlink Worldwide. Healthlink Worldwide is committed to strengthening primary health care and

community-based rehabilitation in the South by maximising the use and impact

of information, providing training and resources, and actively supporting

the capacity building of partner organisations. - ISSN 0950-0235 Reproducing articles

Healthlink Worldwide encourages the reproduction of

articles in this newsletter for non-profit making and educational uses. Please

clearly credit Healthlink Worldwide as the source and, if possible, send us a copy of any uses made of the material.

|

updated: 23 August, 2019

|