|

| |

Issue no. 30 - September 1987

pdf

version of this

Issue version of this

Issue

|

There is much information in this issue that is valuable

and useful. Online readers are reminded, however, that treatment guidelines and health

care practices change over time. If you are in doubt, please refer to

WHO's up-to-date Dehydration Treatment

Plans.

|

Pages 1-8 Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online Issue 30 -

September 1987

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 30 September 1987  Page 1 2

Page 1 2

Women and family health

Half of the people alive today are female. Yet still, in some societies, women's

crucial contribution to human welfare remains undervalued and little is done to ease their

burden and to realise their potential. An appropriate number of healthy pregnancies, safer

birth conditions and good infant and child care are the obvious foundations of family

health. In progress towards greater prosperity, health is an important factor but the

knowledge and the means to reduce health risks in the home and its surroundings still need

to reach many more women. Cultural prejudice, lack of formal education and poverty can

form effective barriers to prevent women from playing a full part in the development

process. Traditional tasks

|

Women play a key role in family health in addition to their

many household and economic responsibilities.

Throughout most of the world, women not only bear and rear the children and carry out

all household tasks but, in rural areas, they are also responsible for growing food for

the family and crops for cash, for carrying home, often over considerable distances, all

water and firewood - and for maintaining whatever form of sanitation exists.

|

|

Their hours of work are long (see="#WOMAN">diagram on page 3) and leave

little time or energy for much else beyond sheer family survival. Measures to improve family health must be designed with the above constraints on

women's time in mind. For example, immunisation and growth monitoring sessions should take

place at times and locations convenient to mothers (see="su30.htm">supplement on

immunisation in this issue). Where fuel is known to be scarce or expensive, advice

about giving suitable oral rehydration fluids should stress the importance of the speed of

response to diarrhoea rather than the use of boiled water. (Page 6

suggests useful alternatives to boiling for water purification.) Women and water - key role Family health very much depends on the quality and quantity of water available for

family use. This issue looks at the key role of women as water handlers in the home and

the community, the beneficial impact that water supply improvements can have on diarrhoeal

disease and primary health care in general, the potential for women to manage

water-related technologies themselves and to act as health educators and agents of

behaviour change. DD gratefully acknowledges special support for this issue from

the Carnegie Corporation of New York. KME and WAMC

|

In this issue ...

- Women, water supply and sanitation

- Immunisation insert

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 30 September 1987  1 Page 2 3 1 Page 2 3

'A Handle on Health' 'A Handle on Health', a new film produced by the International Development Research

Centre (IDRC), shows projects actively involving women and the community in the delivery

of safe water in Ethiopia, the Philippines, Sri Lanka and Thailand. The film demonstrates

how simple, durable handpumps can be designed, tested and manufactured with low cost

materials, as well as providing employment opportunities and saving scarce foreign

exchange. It is available in English and French, and 16mm prints may be borrowed or

purchased. Video cassettes in NTSC, PAL or SECAM signal systems may be purchased in

U-matic, VHS or Betamax formats. For further details please contact: IDRC

Communications Division, PO Box 8500, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K1G 3H9. Award to DD Editor Dr. Katherine Elliott, Scientific Editor of Dialogue on Diarrhoea, received

the 1987 National Council for International Health (NCIH) International Health Award on

17th June 1987 in Washington D. C. The award is given annually to an individual who has

made an outstanding contribution to global health. Dr. Elliott's work in founding and

editing DD was highlighted as a notable achievement. AIDS Newsletter AHRTAG will shortly, be publishing a new newsletter about AIDS. Readers who would like

to be on the mailing list should write to AHRTAG at 85 Marylebone High Street, London W1M

3DE. U.K. The newsletter will be distributed free of charge to subscribers in developing

countries and copies will also be available in bulk. Poster competition So far we have received nearly 100 entries for the children's poster competition

announced in DD 29. To give children some extra time to send

in their posters, the deadline for receiving entries has been extended to 1 January 1988. In the next issue ...

DD will look at the problem of diarrhoeal diseases in urban areas. Training materials The International Training Network for Water and Waste Management

(ITN) has produced a

comprehensive collection of training and information materials on low cost technologies

and approaches based on studies of the World Bank and other agencies. For further details

please write to: Mr Michael Potashnik, Office of the Training Coordinator, Water Supply

and Urban Development Department, World Bank, 1818 H Street, NW Washington D. C. 20433,

U.S.A. Feedback on ORT The Hesperian Foundation is asking for help in gathering material for a future

publication to be called "The Return of Liquid Lost - putting oral rehydration in the

people's hands and terms." The Foundation would like feedback from people in the

field, especially those working at the community or village level. Any information on the

following topics would be especially welcome:

- comparison of different approaches (e. g. ORS packets or home mix, and cereal based

ORT);

- traditional methods of diarrhoea control, local beliefs or practices;

- problems, reasons for success or failure of community programmes;

- educational methods and materials, especially those that are adapted to local

circumstances, resources, and traditions;

- involvement of school teachers, children, women's

organisations, political groups,

agricultural extension workers in ORT promotion and implementation;

- examples of results of participatory research and evaluation;

- observations and results of introducing ORT as a separate programme, as part of a

package of selected interventions, or as a part of a comprehensive plan or intersectoral

approach;

- ideas and suggestions for more effective approaches to ORT (including those within the

context of primary health care and social change).

Please send any comments, reports, or contact names to: Hesperian

Foundation, 1919 Addison St., #304, Berkeley, CA 94704, USA, 1-510-845-1447 -[email protected] -

www.hesperian.org Publications

- The International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh

(ICDDR, B) has

published an Annotated bibliography on chronic diarrhoeal diseases: Specialised

Bibliography Series No. 11 and an Annotated bibliography on water, sanitation and

diarrhoeal diseases: roles and relationships: Specialised Bibliography Series No. 12. For

further details please contact: ICDDR, B, GPO Box 128, Dhaka 2, Bangladesh.

- A new booklet, The treatment of acute diarrhoea: information for pharmacists has

been produced by the WHO/CDD programme and the Federation Internationale

Pharmaceutique.

For further details please contact WHO, CDD Programme, 1211 Geneva 27 Switzerland.

- A study, supported by the WHO/CDD Programme, Options for Diarrhoeal Disease Control:

the cost and cost-effectiveness of selected interventions for the prevention of diarrhoea has

been published by the Evaluation and Planning Centre for Health Care (EPC). Copies are

available from: EPC, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Keppel Street,

London WC1E 7HT U. K. Price:£5.00 including postage and packing.

- An African version of Where there is no doctor: a village health care handbook is

now available from Teaching Aids at Low Cost (TALC), PO Box 49, St. Albans, Herts, AL1

4AX, U. K. Price: f2.50 plus postage and packing.

- The Caribbean Food and Nutrition Institute (CFNI) (PAHO/WHO) in collaboration with the

Ministry of Health, Jamaica has produced a Nutrition handbook for community workers in

the tropics. Published by MacMillan the handbook is available from TALC. Price:

£1.75 plus postage and packing.

- A new edition of Medical Laboratory Manual for Tropical Countries, Volume 1 by

Monica Cheesbrough is now available from Tropical Health Technology, 14 Bevills Close,

Doddington, March, Cambridgeshire PE15 OTT, U. K. Price: £8.55 for surface mail and

£14.05 for airmail.

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 30 September 1987  2 Page 3 4 2 Page 3 4

| Water supply, sanitation and diarrhoea |

The role of women

Preventing diarrhoea in young children requires more than the provision of safer

drinking water and improved sanitary facilities. Mary Elmendorf

discusses the important role of women in family health and hygiene. The availability of safe drinking water in sufficient quantities and sanitary disposal

of human excreta are essential for basic health and can help to reduce deaths from

diarrhoeal diseases. Proper use of improved facilities is the first priority but it is

also important that the faecal-oral route of infection and reinfection is understood,

otherwise loss of life among young children from diarrhoea-associated illness and

malnutrition will continue at a high level. Community involvement Water supply and sanitation projects must be planned and implemented with the full

involvement of those who are going to use the facilities. Particular recognition should be

given to the importance and diversity of the role of women in these activities. In most

cultures women carry out various tasks in relation to domestic water and household

sanitation:

- as acceptors of technologies - traditional and new;

- as users of improved facilities;

- as managers of water supply and sanitation programmes;

- as agents of behavioural change in the use of improved facilities (1).

Women benefit from water supply and sanitation programmes through savings in time and

energy. Experience has shown that they are the main users and managers of water resources

and the main influence on family sanitary habits. They are therefore most able to bring

about changes in basic hygiene behaviour in daily activities. Given appropriate training,

support and equipment, women can help to break the faecal-oral cycle of infection.

|

A Woman's work is never done

A day in the life of a typical rural African woman

- 4:40 Wake up, wash and eat

- 5:00 - 5:30 Walk to fields

- 5:50 - 15:00 Work in fields

- 15:00 - 16:00 Collect firewood return home

- 16:00 - 17:30 Pound and grind corn

- 17:30 - 18:30 Collect water

- 18:30 - 20:30 Cook for family and eat

- 20:30 - 21:30 Wash children and dishes

- 21:30 to bed

|

|

Information and equipment Even though the faecal-oral reinfection route is well

recognised, little has been done

to design facilities and effective health education to help spread this knowledge. All

mothers need basic information, and equipment such as soap and hand basins, adequate

containers for carrying and storage of water, and conveniently located, safe latrines (or

their equivalent). Water alone does not bring sanitation or health. Nor do latrines. Nor

do both if families do not wash their hands after using the latrine. As more water is made

available from pumps or standpipes, appropriate containers and proper use or reuse of

water will be needed to increase health impact. Along with the introduction of improved

community facilities there should be provision for new and appropriate household equipment

to maximise effective use. If there is only one bucket and no money to buy another, of

course it will be used for everything. If there has been only a little water available,

the same water may be reused for washing clothes, dishes and vegetables. If latrines are

not appropriately designed to fit customary habits, they will not be used. If use of

latrines is followed by handwashing their positive health impact can be greatly increased. Questions to be asked Certain questions also need to be asked and answered.

- When women have always washed their clothes in the running stream, will they need, want

or use piped water?

- If water is being used for laundry and bathing, can it be reused in an aqua-privy?

- Do we only think of bathroom planning for elite urban areas?

- How can water for handwashing be made easily available at the latrine?

- How can people be successfully motivated to adopt hygienic practices such as

handwashing?

- How can hands be washed adequately using a minimum of water?

- A minimum of soap?

- No brushes?

- How can hands be dried after washing?

- What are the usual local behaviour patterns?

- Can there be more dialogue with the women to find out how and where they wash clothes,

dishes, hands, children, and themselves?

All of these activities (or lack of them) can be part of the reinfection route unless

precautions are taken. For example, there is the common belief that children's faeces are

'harmless'. They are more infectious than adult excreta and can contribute to

reinfection if they are left in the yard, thrown on a nearby garbage heap, or if soiled

baby clothes are washed along with dishes. Prevention and cure During the last five years oral rehydration therapy (ORT) has become the main weapon in

the treatment of dehydration (which accounts for at least 60 per cent of the deaths from

acute diarrhoea). Early and adequate use of ORT depends primarily on women. But ORT is

only a curative solution; it does not prevent diarrhoea. One long term answer to

preventing diarrhoeal disease is improved hygiene - personal and environmental - both

within and outside the home. The women who have been shown how to use ORT also play key

roles as daily managers of water and sanitation in their homes. They can become the agents

of behavioural changes needed to lower the incidence of recurring diarrhoeal disease. Dr Mary Elmendorf, 2423 Eye Street, N.W., Washington D. C. 20037, U.S.A. 1. Elmendorf and Isely, 1981

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 30 September 1987  3 Page 4 5 3 Page 4 5

| Water supply, sanitation and diarrhoea |

A stimulus to PHC?

Does improving a community's water supply help to increase participation in other

primary health care activities? Some operational research findings suggest that it may do. Researchers from the University of North Carolina looked at the effect of community

participation in water supply projects in Indonesia and Togo (1). The study was based on

the assumption that water supply projects which meet a felt need and involve the community

in their design, construction and operation have an impact on the organisation of the

community and its capacity to take advantage of other health care services. Level of

immunisation coverage for the community was used as the indicator of participation in

other primary health care activities. The relationship between community participation in a water supply project and

increased use of other primary health resources may be for two reasons. First, where a

community becomes organised as a result of a rural water supply project, the process of

organisation itself leads to the community making better use of other primary health care

facilities and resources already available. Second, where a water supply substantially

reduces the amount of time women spend in water collection, more time is available to

mothers to participate in other primary health care activities. One Togolese woman

remarked 'Now that we don't have to spend time carrying water, we have time to discuss

what to do about our village'. Community participation In the study, a project was defined as 'participatory' when community involvement goes

beyond donation of land, labour and materials to active involvement of men and women in

decisions related to the planning, implementation, funding, maintenance and evaluation of

a water supply project. The selection of the sites was based on community water supply

projects that had been in, use for at least three years and where similar nearby areas

remained unserved (and where an immunisation campaign has been undertaken in both the

served and unserved areas). The research project collected information from the two

communities and compared them. Results from Togo show that villages involved with community-based rural water supply

projects have an average DPT (diphtheria, pertussis and tetanus) completion rate of 54.5

per cent among children aged 12-36 months, In villages with non-community based water

projects the average rate is 39.8 per cent. In Indonesia, the DPT completion rates among

children aged 3-14 months in the participatory and non-participatory water supply villages

are 60 per cent and 49 per cent respectively. The study found that effective community

participation requires about four months of preparation with the community. The follow-up

phase of this activity will examine knowledge of ORS m communities with varying levels of

participation. 1. "Community Participation in Water Supply Projects as a Stimulus to Primary

Health Care: Lessons Learned from AID-supported and other Projects in Indonesia and

Togo." by E. Eng, J. Briscoe and A. Cunningham. WASH Technical Report No. 44. Readers are welcome to request these studies from WASH, 1611 N. Kent Street,

Room 1002, Arlington, VA 22209, U.S.A. Hygiene education

Does teaching people to use improved water and sanitation facilities effectively

reduce childhood diarrhoea? Bonita Stanton and John

Clemens report from Bangladesh. Uncertainty about the usefulness of teaching hygiene is the result of using

inappropriate water and sanitation educational interventions in the past. These have often

included too many messages, about behaviour which is culturally unacceptable or too

costly, and recommending actions that have not been shown to reduce diarrhoea rates. In Dhaka we planned to find interventions that were already being used effectively and

to teach about these. We looked at this in two ways. First we compared the hygiene

practices in families with high and low child diarrhoea rates (a case-control study).

Second we trained one group of families in the domestic practices associated with less

diarrhoea and compared the improvement with the state of health in untrained families (a

controlled trial). We looked at current practices of washing and sanitation which appeared to influence

the number of attacks of childhood diarrhoea in slums in Bangladesh. These would form the

basis for simple education interventions, that is, appropriate teaching messages. We

studied approximately 1,900 families, in 51 clusters of 38 families, throughout Dhaka

city. Each cluster was located near a volunteer community health worker from the Urban

Volunteer Programme of the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research,

Bangladesh (ICDDR, B). The rates of diarrhoea of all children under six years of age in

these families, and the hygiene practices of a 13 per cent sample of these families were

monitored between October 1984 and January 1985. After ensuring that the numbers and ages

of children were similar, the families were ranked from highest to lowest according to

rates of diarrhoea. Families with the highest diarrhoea rates, the top 25 per cent, were

chosen as "cases" and families with no episodes of diarrhoea in the study period

as the "controls'*. The social structure and the economic status of the case and

control families were also checked to see if they were the same. The hygienic practices of

the high-diarrhoea families were compared with those of the low-diarrhoea families. Of

many practices observed, only three differentiated the high-diarrhoea from the

low-diarrhoea families. First, fewer case mothers (53 per cent) than control mothers (82

per cent) washed their hands before serving food. Second, more toddlers of case families

(80 per cent) than of control families (33 per cent) defaecated in the families' living

area. Third, in more case control families (47 per cent) than in control families (30 per

cent) children put garbage and waste products in their mouths.

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 30 September 1987  4 Page 5 6 4 Page 5 6

| Water supply, sanitation and diarrhoea |

Effectiveness of teaching The three hygienic practices which were associated with less diarrhoea were taught to

some families but not others. (This was a randomised controlled trial of hygiene

education.) Since these hygiene practices were already being used by some families, we

presumed them to be culturally acceptable and financially feasible. The same 51 clusters of 38 families were used in this teaching study. A team of

interviewers and observers collected information about diarrhoea and related practices for

five months before and six months after the start of the hygiene teaching campaign. To

make sure that the observations were systematic, the team used a list of specific actions

to look for in all the families. The 51 community clusters were matched up in pairs for

age of children and diarrhoea rates. Then one of each of the community pairs was selected

in an unbiased way (random selection) for hygiene education. There were 25 communities

chosen for "teaching" (intervention group) and 26 communities for "no

teaching" (the control or no intervention group). In the teaching team were the 25

volunteer community health workers from the 25 intervention areas and also other trainers.

Educational materials included stories with pictures, flannel boards with figures, before

and after photographs, and 'do' and 'don't' pictures. The teaching went on for two months

in 1985 and included discussions with groups of women, children and mixed audiences

including men. After the teaching period, one of the hygiene behaviours, mothers washing

hands before serving food, was seen significantly more often (49 per cent) in the

communities where this had been taught than in control communities (33 per cent). Episodes of diarrhoea In the first six months following the teaching intervention there were 653 episodes of

diarrhoea (a rate of 4.29 episodes per 100 person-weeks of observation) in the

hygiene-taught intervention communities. By contrast, there were 914 episodes of diarrhoea

in the control communities which had not been taught (a rate of 5.78 episodes per 100

person-weeks of observation). This difference was statistically highly significant (p<

0.0001), indicating that the hygiene teaching had made a difference. This difference was

seen in all age groups, but was most striking in the 2 and 3 year old children. This

toddler age is when children are most vulnerable to diarrhoea in Bangladesh. In summary these results show that simple educational messages designed to alter

behaviours known to be associated with childhood diarrhoea really can change what mothers

do. Bonita Stanton, MCH Specialist, The World Bank, Resident Mission in Bangladesh,

222 New Eskaton Road, GPO Box 97, Dhaka, Bangladesh, and John Clemens, Epidemiologist,

ICDDR, B, PO Box 128, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Improved facilities

The effect of improved water supply and excreta disposal on infectious diarrhoeas

in Malawi and the Philippines. In Malawi, the environmental improvements in a rural area near Zomba are provided

through the Rural Piped Water Supply and Hygiene Education Programme. This programme

supports self-help gravity water supply systems for communities, and education about

hygiene and latrine construction. In Cebu, improved water supplies are available through

the municipal water system and public and private boreholes. Improved excreta disposal

facilities (flush toilets, water-sealed toilets or pit latrines) are available to

two-thirds of this peri-urban population. Clinics were selected to include families attending who had improved environmental

conditions and those who did not. Children were categorised as 'exposed to good

environmental sanitation' if their families had an improved water supply and improved

excreta disposal facilities; all other children were considered 'not exposed'. The studies were based on children brought to the same clinics for one of several

diseases considered to be of similar severity to diarrhoeal disease. Control diseases were

mainly malaria and acute respiratory infections in Malawi, and acute respiratory

infections in the Philippines. Although both studies were based on children attending several clinics (3 in Malawi, 16

in the Philippines), neither met the desired sample size (460 cases and 460 controls)

since recruitment was limited to the 4-5 month periods corresponding to the warm-weather

diarrhoea peaks in each location. Data were collected both at the clinic and in follow-up

home visits. Additionally, in the Philippines study, rectal swabs were collected and

analysed for all cases and controls for rotavirus, Campylobacter, enterotoxigenic E.

coli, Salmonella, Shigella and Vibro cholerae. Impact of environment The effects of improved water supplies and excreta disposal on diarrhoea morbidity were

assessed. Results suggested that environmental improvements are associated with a

reduction in diarrhoeal disease of about 20 per cent during the warm, rainy season for the

particular populations studied. For the Philippines study analysis, cases were restricted to those children with

clinical diarrhoea who were positive for any enteric pathogens examined, and controls were

restricted to those controls who were negative for all diarrhoea pathogens. The measure of

association between disease and environmental sanitation was markedly stronger than that

found in the broader analysis, with a 40 per cent reduction in diarrhoeal disease

associated with the environmental improvements. There is evidence that, in some poor socio-economic conditions, single environmental

improvements may be necessary, but are insufficient to affect health status. If this is

so, then these two studies would indicate that additional activities promoting clean water

supplies, good sanitation and hygiene education could result in substantial health

impacts. Beverly Young and John Briscoe, Department of Environmental Sciences and

Engineering, School of Public Health, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27514,

U. S. A. and Jane Baltazar, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Institute of

Public Health, University of the Philippines, 625 Pedro Gil, Ermita, Manila, Philippines.

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 30 September 1987  5 Page 6 7 5 Page 6 7

Water purification

Most surface water - from rivers, streams and ponds - needs to be purified before it is

fit to drink, as it may be contaminated with soil, decayed vegetable matter, and human or

animal faeces. Drinking contaminated water is a major cause of diarrhoea. This article

briefly describes various ways in which water can be purified. The four most common

methods of water purification are:

- storage;

- filtration;

- chemical disinfection;

- boiling.

Storage Contaminated water can be made safer to drink if it is stored for at least two days.

Within that time many harmful organisms will die, and most of the dirt will sink to the

bottom of the pot. But this will not kill all pathogens and is not effective for

very dirty water. Storage containers can be made of metal, glass, plastic, or glazed ceramic materials.

The use of earthenware pots should be avoided if possible, because of the risk of

bacterial growth in the porous clay walls. Water can be purified by storage in the home

using three pots. Two big pots are used for fetching water on alternate days. The first

pot is allowed to stand for two days. Then the clear top water is carefully poured into

another (smaller) pot for drinking. The remaining water can be used for washing. When the

first pot is empty it is cleaned and refilled, then it is allowed to stand for two days

again. Meanwhile the second big pot is used in the same way as the first. In this way each

day's drinking water has been standing for at least two days before it is used. Storage

containers must be covered to prevent the water from becoming contaminated, to stop algae

from growing and to prevent evaporation. Filtration A sand filter will remove most of the suspended organic material in water, but it will

always let viruses and some bacteria pass through. For this reason, it is best, if

possible, to boil or chlorinate water after it has been filtered. Household sand filter - Using wide, earthenware pots, about 750mm high. 1 litre

of water can be filtered every minute. Inside the pot put a thin layer of small stones.

Cover this layer with a layer of charcoal, over which put a thick layer of sand. Another

layer of gravel can be put on top to stop the sand from being disturbed when water is

poured in. The filtered water passes through a tube from the bottom of the filter pot into

a collecting vessel. A similar version can be made from three or four clay pots standing

on top of each other. The pots, in turn from the top, contain gravel, and charcoal. In the

four-pot version the lowest pot is used for storage of the treated water. The filter is

simple to make using local materials, and can be kept working well by occasionally

removing the top layers and replacing them with fresh gravel and charcoal. Chemical disinfection Iodine - Iodine can be used for disinfecting water

and is excellent provided the water is not too dirty. WHO recommend two drops of 2 per

cent tincture of iodine per litre of water. If the water is thought to be highly polluted

then the amount should be doubled - such amounts are not harmful but will give the water a

slightly medicinal taste. Iodine compounds, such as tetraglycine potassium tri-iodide are

supplied as tablets which are claimed to be effective against amoebic cysts, and some

viruses and bacteria. Chlorine - Chlorine is a good disinfectant for drinking water as it is effective

against bacteria associated with waterborne diseases. Bleaching powder contains about

25-30 per cent chlorine. (WARNING: Keep all kinds of bleach away from children and out

of eyes. Do not swallow.) About 37cc (2½ tablespoons) of bleaching powder dissolved in 0.95 litre (1 quart) of

water will give a one per cent chlorine solution. To chlorinate the water, add three drops of one per cent solution to each 0.95 litre (1

quart) of water to be treated (2 tablespoons to 32 imperial gallons), mix thoroughly and

allow it to stand for 20 minutes or longer before using the water. Alternatively, simple chlorinators, which dispense chlorine at a constant rate into a

water supply, can be bought or made with local materials. An example is a diffuser

chlorinator which is used in non-flowing water supplies like wells, cisterns and tanks. It

consists of a pot filled with coarse sand and chlorine powder, submerged in a water

supply. The chlorine seeps into the water supply through holes in the container. Diffuser

chlorinators have slow rates of disinfection and are most effective in wells or tanks not

producing or holding more than 100 litres/day. Boiling Boiling is the best way of destroying germs in water. The water must be brought to a

good 'rolling' boil (not just simmering) and kept boiling for ten minutes (this may need

to be longer at high altitudes). Store the water in the container in which it has been

boiled, or, if pouring the water into another container make sure that it is clean. There

are certain issues to consider when boiling water to purify it:

- Pathogen survival - some pathogens (E coli and faecal

coliforms) and cysts such as

giardia lamblia may be killed at lower temperatures than boiling point (about 50 - 63°C

rather than 100°C).

- Cost - boiling water for ten minutes or more may be impractical where fuel is expensive

or difficult to obtain. Boiling and cooling water also takes time.

- Recontamination - unless boiled water is carefully stored and used, it may be

recontaminated by dirty containers, insects, dirty hands etc.

Other methods Other methods have been used to purify water with differing levels of success. These

include using sunlight, alum, ash, clay and traditional materials such as seeds and

plants. Some studies have shown that exposing water to sunlight for several hours in a

transparent container can reduce the number of enteric pathogens. A recent study in

Bangladesh showed that potash alum prevented bacterial growth in ORS solution when used in

a concentration of 0.05-0.1 per cent. More research is needed to study traditional and

alternative methods of purifying water. The Editors would welcome letters from readers

about their own experiences of treating water using traditional methods. For more detailed information about the methods of water purification described

above, please write to Dialogue on Diarrhoea at AHRTAG.

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 30 September 1987  6 Page 7 8 6 Page 7 8

Bangladesh: the Mirzapur project

The project began in 1984 at Mirzapur, 60 km north of Dhaka, in an area with

approximately 800 households and 4,500 people. Interventions include installing handpumps

and double-pit latrines, and a health education programme. A similar population 5 km away

where no intervention was made serves as a control group. The project is field-testing, in

a rural setting, a newly developed handpump (the Tara pump). It aims to assess the

acceptability of the water and sanitation hardware, and to measure the impact on health,

particularly nutritional status, diarrhoea, and intestinal worm infestations in children. The Tara handpump

|

The Tara handpump The Tara handpump is a locally manufactured, non-suction, low lift pump made mostly of

plastic components. It can extract water where the static water table has fallen to a

level at which conventional suction pumps become inoperative (about 7 m), and could be

used in all areas in the delta regions of Bangladesh. The pump is easy to operate, simple

to maintain and provides good quality water in large volumes throughout the year. 156 Tara

handpumps have been installed in the intervention area.

|

|

Together with some UNICEF No. 6 pumps already in place, this makes the borehole to

population ratio about 1:30. In the control area, previously installed UNICEF pumps each

serve approximately 110 persons. To begin with all Tara pumps were maintained by project staff; now 30 pumps are

maintained by trained community women volunteers. They are checked once a fortnight and on

average have been found to require 3 to 5 minor repairs a year. Water consumption per

person varies according to the number of people using the pump. Water use per person is

much higher when pumps serve 20 persons or less than larger numbers. Since the project

began, use of handpump water for most domestic purposes has increased significantly in the

intervention area, whilst remaining at the same level in the control area. Double-pit, water-sealed latrines have been installed in more than 95 per cent of

households in the intervention area. Departing from traditional practices, these were

placed close to the households, and so were less readily accepted by the community than

the water component of the project. Women as health educators At first health education was conducted through project staff only. In 1985, however,

this was gradually transferred to women volunteers from the community. During 1986 women

from 25 per cent of households were trained as health educators and it is hoped that women

from all households will be participating by the end of 1987. Health education messages

have been periodically reviewed and modified. Detailed weekly recall data on diarrhoea in

all age groups, quarterly nutritional measurements and yearly parasite prevalence data in

children under five years of age are being collected. Socio-economic status, water

consumption, latrine and handpump performance, and knowledge, attitudes and practices

relating to water and sanitation are also being recorded. During the study period the

incidence of diarrhoea in children below five years of age has decreased in both areas but

substantially more so in the intervention area. The project is now starting its final

phase and findings will be reported in 1988. Dr Bilqis Amin Hoque and Dr K M A Aziz, International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease

Research, Bangladesh, GPO Box 128, Dhaka 2, Bangladesh.

|

Zimbabwe: encouraging families to build latrines

|

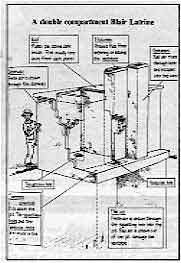

A double compartment Blair Latrine

The government in Zimbabwe is encouraging families to participate in constructing and

maintaining ventilated pit (VIP) latrines, to improve sanitation in rural areas. The Blair

ventilated latrine is very popular because:

- it does not smell

- it does not attract flies

- it is safe to use

- it is very private

- it costs little to build it can be used as a private bathing place

- it is easy to maintain and lasts for many years

Ministry of Health, Box 8204, Causeway, Harare, Zimbabwe |

|

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 30 September 1987  7 Page 8 7 Page 8

Training medical students The rural Ibarapa Community Health Programme in Oyo State, Nigeria, is the public

health and primary health care training site for fourth year University of Ibadan medical

students. In September, 1985, a model ORT unit was established at the Igbo-Ora Rural

Health Centre, with assistance from UNICEF Nigeria. Before setting up the ORT Unit,

medical students surveyed diarrhoea prevalence, and gathered valuable cultural and

behavioural information which forms the basis of the Unit's health education services. All

students must, during their eight-week posting in Ibarapa, conduct epidemiological

projects. In carrying out diarrhoea surveys, the students not only learn research and

statistical methods, but also gain insight into the problems of diarrhoea and its

management. They found that almost all mothers recognised diarrhoea as increased frequency

of watery stools, and that teething, bad food and dirty stomach were most commonly

believed to cause the disease. They learned that while nearly two-thirds of mothers had

heard of salt-sugar solution (SSS), less than one-fifth actually considered it as first

line management for diarrhoea. Changes in feeding patterns during diarrhoea were also

noted, with beans being forbidden during diarrhoea and bland maize porridge being

preferred. Dialogue with mothers Once the ORT unit !vas functioning, students worked on a rota basis. They now take part

in assessment of children brought to the unit, giving ORS, monitoring progress, and above

all in health education. An interactive health education process has been developed and

adapted UNICEF posters are used as a basis for discussion with mothers. Mothers' ideas are

sought and their existing knowledge built upon to help them gain a greater understanding

of the problem. For example, when mothers say teething causes diarrhoea, staff members ask

questions about the child's behaviour during teething. From this discussion, mothers

realise on their own that a teething child puts all manner of dirty objects into its

mouth, thereby causing diarrhoea. Step by step, mothers are guided through simple ideas

about recognition, cause, prevention, dangers and treatment of diarrhoea. They then take

part in a demonstration of making home SSS. The medical students also take ORT education

into the community. They discuss the problem of diarrhoea with children during the regular

school health lessons, and with community members during weekly PHC village supervisory

visits. Recently a group of students has conducted a survey on risk factors. They found that

all mothers believe in handwashing, but that children whose mothers use both soap and

water have less diarrhoea than where water alone is used. The visible presence of

children's faeces in the immediate home environment was associated with higher diarrhoea

prevalence. Users of well water reported more diarrhoea in their pre-school children than

those with access to tap water. Although all medical students have heard of ORT and SSS prior to coming to

Ibarapa, few

know the correct formula for home made solution, its main purpose and the means of

administration. Post-test results at the end of the posting show that virtually all can

make the drink correctly and understand its efficacy. During the early days of oral

therapy for diarrhoea, one of the major problems was acceptance of the idea by health

professionals, If up and coming generations of physicians (and other health workers)

participate in ORT programmes during their basic training, they will hopefully grow to

accept ORT as a natural and desirable part of diarrhoea control and primary health care. William R. Brieger and Jayashree Ramakrishna, Department of Preventive and Social

Medicine, University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria.

Motivating pharmacists We have a particular problem in Egypt in our ORT programme. When a child develops

diarrhoea, many mothers do not consult a health facility or private physician, but, for

economic reasons, go directly to a pharmacy asking for medicines to treat diarrhoea. The

pharmacist most likely gives the mother 2-3 medicines and ORS is not always one of them.

The motives are financial as selling more medicines brings more income. In any training

programme, pharmacists should be included, motivated and in one way or another given

compensation for lost income from not selling conventional "anti-diarrhoeal

drugs". In Egypt one method used is to supply free of charge special containers for

preparation of ORS, which the pharmacists are allowed to sell to buyers of ORS, giving

them an additional income. However, we are still very far from making all pharmacists

advocates of ORS. Professor Mahmoud El-Mougi, Professor of Paediatrics, Bab

El-Sha'reya University

Hospital, Diarrhoeal Disease Research and Rehydration Centre (DDRRC), 32 Madrasset Waley

El-Ahd Street, Abbasseya, Cairo, Egypt.

Editors' note: Anti-diarrhoeal drugs are inappropriate, ineffective and

sometimes dangerous for young children. Pharmacists should not sell these drugs to

mothers for their children and compensating them for not selling them would therefore be

inappropriate. Pharmacists need clear guidelines and professional information from

pharmaceutical associations about the correct prevention and treatment of dehydration. In

many countries, national pharmacists' associations have agreed to distribute ORS packets

free of charge. Where this would cause financial problems for pharmacists, governments

could pay a professional fee for acting as a distribution centre for ORS packets. (See="#page2">page 2 of this issue: WHO Manual for Pharmacists).

|

Scientific editors Dr Katherine Elliott and Dr William Cutting

Managing editor Kathy Attawell

Editorial advisory group

Professor J Assi Adou (Ivory Coast)

Professor A G Billoo (Pakistan)

Professor David Candy (UK)

Professor Richard Feachem (UK)

Dr Shanti Ghosh (India)

Dr Michael Gracey (Australia)

Dr Norbert Hirschhorn (USA)

Dr Claudio Lanata (Peru)

Professor Leonardo Mata (Costa Rica)

Dr Jon Rohde (USA)

Dr Mike Rowland (UK)

Ms E O Sullesta (Philippines)

Professor Andrew Tomkins (UK)

Dr Paul Vesin (France)

Dr M K Were (Kenya) With support from AID (USA), ODA (UK), UNICEF, WHO Publishing partners

BRAC (Bangladesh)

CMAI (India)

CMU (China)

Grupo CID (USA)

HLMC (Nepal)

lmajics (Pakistan)

ORANA (Senegal)

RUHSA (India)

Consultants at University Eduardo Mondlane (Mozambique)

|

Issue no. 30 September 1987

Page Navigation

This edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online is produced by Rehydration Project. Dialogue on Diarrhoea was published four times a year in English, Chinese, French, Portuguese, Spanish, Tamil,

English/Urdu and Vietnamese and reached more than a quarter of a million readers worldwide. The English edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea was produced and distributed by Healthlink Worldwide. Healthlink Worldwide is committed to strengthening primary health care and

community-based rehabilitation in the South by maximising the use and impact

of information, providing training and resources, and actively supporting

the capacity building of partner organisations. - ISSN 0950-0235 Reproducing articles

Healthlink Worldwide encourages the reproduction of

articles in this newsletter for non-profit making and educational uses. Please

clearly credit Healthlink Worldwide as the source and, if possible, send us a copy of any uses made of the material.

|

updated: 23 August, 2019

updated: 23 August, 2019

|