|

| |

Issue no. 51 - December 1992

pdf

version of this Issue version of this Issue

|

There is much information in this issue that is valuable

and useful. Online readers are reminded, however, that treatment guidelines and health

care practices change over time. If you are in doubt, please refer to

WHO's up-to-date Dehydration Treatment

Plans.

|

Pages 1-8 Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online Issue 51 -

December 1992

|

DDOnline

Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 51 December

1992  Page 1 2

Page 1 2

Evaluation is a useful tool - not a threat

Evaluation can be:

a friend, not a foe

an education, not an enemy

the opportunity to do better.

|

A good evaluation enables a community to take sound decisions

about its future. For some people, the word 'evaluation' causes

alarm. They imagine it is about measuring how hard people are working and then criticising

anyone who is not doing well. However, this impression is mistaken.

|

Evaluation can help and encourage health workers. This issue of DD explains

how evaluation works and how it enables health workers to provide a better service for

people. Evaluation can be looked at as a cycle of steps.

- Setting the objectives

Evaluation involves comparing what we are doing with what we set out to do. Clear

objectives have to be set at the start of a programme. For example, we will train 80 per

cent of mothers in the district to prepare oral rehydration therapy (ORT) by next

December.

- Action to achieve the objectives

Next, we work on activities to achieve our objectives. Many of us are so busy carrying out

the work that we rarely stop to ask how we are doing.

- Looking at what we are doing

Asking questions, systematically observing, measuring and noting what has been achieved is

the next stage. This may involve counting the numbers of mothers trained, testing if they

can prepare ORT and asking if they have given ORT to their children. It is worth involving

not only the health team, but also the people who use the service. This is known as

participatory evaluation.

- Analysing the results

If our objectives have been clearly defined we should be able to compare what we have

achieved with what we set out to do. If numerical targets have been set, statistical tests

can be applied to see if the changes since the start of the programme are true differences

and significant.

- Communicating the results

The results should be shared with people who have planned the programme, those who have

carried out the work, people who have collected information for the evaluation, and those

who have received the service. Failure to feed back the results leads to lack of interest

and falling standards of observation.

- Improving the service

This is the vital, final step in the evaluation cycle. It is the real purpose of

evaluation - to do things better. Evaluation should be a partnership in which health

workers and communities work together for improved health care.

William Cutting and Katherine Elliott

|

In this issue:

- Evaluation techniques -surveys and sample selection

- Breastfeeding twins - pictures of positioning

- Exclusive breastfeeding - your questions answered

|

|

DDOnline

Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 51 December

1992  1 Page 2 3 1 Page 2 3

Evaluation means asking: how are we doing? Collecting information to measure performance is a vital part of health work. Only

when we have assessed how we are doing can we plan to do it better. DD explains

what evaluation is and how it is done. Most of us working in health have at some point questioned what we are achieving. We

already carry out our own personal 'evaluations', for example, by thinking about whether a

health education discussion went well, by asking colleagues' opinions on progress and by

listening to changes in community opinion. Evaluation is simply a more systematic way of measuring progress and assessing whether

a programme or activity is achieving its goals. Why evaluate? A common belief is that evaluation involves outside 'experts' collecting complex

statistics for funders or government departments. However, evaluation concerns everyone.

It helps us to look at what we are doing and to work out how to do it better. For example,

a community health worker needs to know if her weekly village visits have helped mothers

understand how to treat diarrhoea. A supervisor of wells must find out if the community is

actually using the wells. What is evaluation?

Evaluation is any process designed to assess whether a programme or activity is

actually doing what it set out to do, and to suggest ways in which it could be altered to

improve effectiveness. In this article the term evaluation includes continuous monitoringand periodic reviews of performance as well as 'after the event' evaluation. Evaluation can help us to:

- see if the programme is moving in the right direction

- identify and explain successes and failures

- compare the effectiveness of different activities or parts of a programme

- collect information for future planning.

It is not possible to answer all potential questions about every aspect of a programme.

Evaluations must focus on the most important questions. A good rule is never to ask a

question unless you can see in advance how the answer might be used to change the

programme. Collecting data which are not used is a waste of

resources and is demoralising for staff. When to evaluate?

Evaluation should be part of programmes from the start, not added at the end. It should

be planned and budgeted for in advance. All the stages of a programme can be evaluated,

including the inputs, the specific activities within the programme and the overall impact.

Trying to cover everything, however, would leave programme managers and health staff

little time for anything except evaluation! Sometimes a programme or activity needs to be tested before it is put into practice on

a wider scale. The testing is known as a pilot programme. Its main purpose is to evaluate

whether the programme works, and is worth repeating or adapting for use in other

communities. Regular monitoring, especially at the early stages of a programme, can identify good or

inadequate performance by staff. Good practice can then be encouraged or extra training

planned for staff experiencing problems in their work. It is usually inappropriate to try to evaluate whether a programme has achieved its

ultimate aim of having had a health impact (e. g. to reduce infant mortality). To do this

requires specially designed research and substantial resources. For example, a programme

that aims to make children healthier through better feeding may promote exclusive

breastfeeding. The programme should evaluate what proportion of young infants are

exclusively breastfed. It does not need to prove that infants who are exclusively

breastfed suffer less diarrhoea and have a lower death rate than those who are not

exclusively breastfed. This link has already been widely shown.

Evaluation techniques include:

- Questionnaires - written questions used to gather information from

selected people

- Interviews - verbal questions

- Observation - methodically watching and noting down what people do.

This can sometimes be more reliable than asking questions, because people will often say

what they think an interviewer wants to hear rather than what they actually do.

- Group discussions - discussions guided by an experienced person who can

assess group knowledge or attitudes.

|

|

|

DDOnline

Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 51 December

1992  2 Page 3 4 2 Page 3 4

There are three main stages in evaluation: planning; carrying it out;

and analysing and reporting the results. How to plan?

First of all we should be clear about the aim of a programme or an intervention. For example, the aim of a hygiene education

programme may be to decrease diarrhoea episodes in young children. That aim then needs to

be narrowed down to goals that can be measured - known as indicators.Indicators for a hygiene education programme could be:

- the number of children who wash their hands after defecating

- changes in hygiene practices related to food preparation

- mothers' understanding of the need for handwashing.

It is best to keep the evaluation simple and decide on one or two key indicators. That

way information collection is easier and will take up less time and money. How to evaluate? Evaluation measures the effect of an intervention by assessing the situation before and

after it was introduced. Therefore information needs to be collected before the

intervention (known > baseline information). Usually, evaluation will need a mix of approaches. These include the collection of quantitative information (statistics or numbers), either

through routine reports (e. g. how many mothers have attended health education sessions)

or surveys (e. g. how many children wash their hands after defecating). Equally important

is the collection of qualitative (descriptive)

information; for example, through in-depth interviews (e. g. asking mothers what they

think are good practices in preparing food) and group discussions (e. g. asking groups of

mothers if they think health talks given by clinic staff are useful). Different evaluation techniques are appropriate for different indicators. For example,

a water supply project may decide that a house-to-house survey recording sources of

drinking water in the home is the best technique for measuring use of an improved water

source. Alternatively, a group discussion may be the best way of evaluating mothers'

understanding of the need to use clean water. Clearly, good quality data are important. However, a common problem is that evaluators

try to be too precise with their answers. Trends are often more important than specific

figures (e. g. about three-quarters of the households in a community collect their water

from the new well, compared with about a third before the health education talks started). Who should be involved?

|

Health workers and community members should be involved in the

planning of an evaluation.

Decisions about how to carry out an evaluation should ideally involve everyone affected

- the staff, community, funders and programme managers. Evaluations decided upon by

planners in capital cities may succeed in collecting statistics, but vital information

about local attitudes may be missed.

|

|

Community members provide valuable information about local beliefs, practices and

leadership. They can also point out where evaluation techniques may not be appropriate.

For example, trying to accurately count infant deaths in a community may be limited by

local taboos against talking about children who have died. If community members and staff are consulted beforehand and involved in the process

they will also be more likely to be committed to the programme's aims and to learn from

the results of the evaluation. A good evaluation can enable communities to see their own

progress and to take sound decisions about their future.

| Evaluation is like a bus journey. You have to know: where you want to go;

whether the route is direct; how fast you are travelling; and how to recognise when

you have arrived. |

What to do with results? Once information has been collected it needs to be analysed and reported. The

evaluation must give a clear answer to the question: 'How are we doing? ' It should

indicate what has been successful and what has not, and give constructive and practical

suggestions as to what might be done to improve things. It is very important that this

information is fed back to all staff concerned with the programme. This will help them

identify what they have achieved and where they could do better. An evaluation report should be short and to the point. Statistics must be presented

clearly and should be used to illustrate change (or lack of it) rather than to confuse the

reader with too much detail. Reports do not always need to be written. Verbal reports, or

other more creative strategies for communicating the results to the community (such as

plays and pictures), can be devised (see="#page6">page 6). Sharon Huttly and David Ross, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Keppel

Street, London WC1E 7HT, UK.

Glossary of terms

|

| Baseline information |

Facts about the situation before an activity or programme starts |

| Data |

Facts collected for a special purpose |

| Indicators |

Measurable 'markers' of progress |

| Intervention |

The introduction of an activity or programme designed to bring about change |

| Monitoring |

Continuous information collection to assess the functioning of the programme or

activity |

| Quantitative |

Information based on numbers or statistics |

| Qualitative |

Descriptive information about ideas, beliefs and behaviour |

|

|

DDOnline

Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 51 December

1992  3 Page 4 5 3 Page 4 5

WHO's household survey Surveys are a good way of collecting information from a limited number of people

to provide a picture of a wider population. Elizabeth Sherwin

reports on a household survey to find out how diarrhoea is managed at home. The World Health Organization developed a revised standardised household survey in 1989

to help national programmes to better evaluate home treatment of diarrhoea. Since that

time about 90 surveys using this approach have been carried out in over 30 countries. The survey provides important information on home management by focusing on seven key

indicators of appropriate treatment. These are:

- oral rehydration salts solution (ORS packets) use

- oral rehydration therapy (home made sugar-salt solution, other recommended home fluids

and/or ORS) use

- increased fluid intake

- continued feeding

- correct ORS preparation

- correct home fluid preparation

- the proportion of carers who know when to seek medical help.

Information is collected by interviewing caregivers (usually mothers) of children under

five years old who have had diarrhoea in the 24 hours before the survey. Children under five years old are identified using a cluster sampling method. This

means groups or clusters of nearby households are chosen randomly using a chance selection

(see="#selection">box on page 5). The survey usually comprises 30-60 clusters

each containing 100-200 children under five. The surveyors then go from house to house and

identify the children who have had diarrhoea in the last 24 hours.

|

Mothers of young children who have had diarrhoea in the past 24

hours are asked about the treatment they gave. Standard questions asked of mothers include the amount of food given during episodes of

diarrhoea, the signs and symptoms that would prompt them to seek help from a health

worker, and whether they treat their children with drugs.

|

These questions are adapted to take account of local language and beliefs. The

surveyors also watch mothers preparing ORS and home fluids. Planning for the survey takes 3-4 days and should be done a month or two in advance. It

involves:

- discussion of objectives

- selection of locations and timing (best done in the peak diarrhoea 'season')

- choosing the sample size

- randomly selecting clusters

- identifying surveyors (20-30) and supervisors

- preparing a budget

- adapting questionnaires for local use.

Between planning and carrying out the survey, preparations have to be completed

including: obtaining government and local community approval; making arrangements for

training, transport, accommodation and translation (if necessary); testing out and

printing of questionnaires; and recruitment of supervisors and surveyors. The actual survey takes about a month, including one week for training, 2-3 weeks for

data collection, and one week for data analysis and report writing. The data analysis can

be done by hand or using a simple computer programme. Using the results The survey provides important information about what happens at home - the place where

diarrhoeal disease control programmes succeed or fail. The findings highlight the

communication messages that need to be devised for mothers. Examples of where household surveys have provided useful information include:

- In Nepal a comparison of survey data from 1985 to 1990 showed little improvement

in ORS and ORT use rates, even though most mothers knew about ORS. The programme therefore

decided there was a need to make ORS more available and to convince more mothers of its

value. In order to increase the use of ORT, the programme decided to recommend home fluids

in addition to sugar-salt solution.

- A survey in Vanuatu, in the Pacific, indicated the need to recommend home fluids,

and to establish 'ORT corners' in health facilities to provide better information to

mothers on the preparation of ORS and the importance of giving more fluid.

- In Kenya a survey highlighted the fact that many mothers cannot prepare ORS

correctly. The main reasons identified were the availability of a variety of ORS packets

requiring different amounts of water and inconsistent health education messages

recommending different home containers for measuring. As a result of the survey, one

standard packet and a limited number of containers will be promoted.

Dr Elizabeth Sherwin, CDD, WHO, CH- 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland.

|

|

DDOnline

Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 51 December

1992  4 Page 5 6 4 Page 5 6

|

Providing a global picture

Findings from WHO household

surveys around the world have been analysed to produce a global picture of progress on

action to reduce deaths from diarrhoea.

They have shown that global rates for use of ORS and ORT are increasing, although the rate

of increase has started to level off over the last few years. At the end of 1991, the

global ORT use rate was estimated to have been 38 per cent.

|

|

Surveys in 1989-90 showed that when children have diarrhoea:

- more than 90 per cent of mothers worldwide continue to breastfeed

- most children (60-70 per cent) are offered more food, or at least their normal amount

- a low proportion of mothers (15-30 per cent) increase the amount of fluid they give

children

- water is the most common liquid given, followed by tea, coffee and various infusions.

These findings show the urgency of getting across to mothers the simple message that

children with diarrhoea need to drink more.

|

Training manuals

A training manual is available from WHO on how to plan, conduct and analyse a household

survey. It contains:

- sample size calculations

- guidelines for planning and conducting a survey

- information about training

- questionnaires and explanations of each question

- instructions for analysing data.

Guidelines for conducting surveys at health facilities are also available. A revised

household survey incorporating questions on acute respiratory infections and breastfeeding

will be available in 1993. Contact: WHO/CDD, CH-1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland. Vietnam measures progress Household and health facility surveys have been used in Vietnam to chart a

remarkable improvement in appropriate treatment of diarrhoea. Vietnam's diarrhoeal disease control programme (CDD) began in 1982 in four provinces

and has expanded over the last decade to cover the whole country. Household surveys in different parts of the country in 1986 and 1987 revealed several

areas of concern: a very low rate of use of ORS and ORT (7 per cent and 13 per cent

respectively); with only just over half of mothers (54 per cent) continuing to feed

children during diarrhoea, while slightly more (65 per cent) continued breastfeeding

during diarrhoea. Surveys of health facilities during the same period showed a high usage of drugs (75

per cent) and of IV therapy (42 per cent). Only a quarter of health staff surveyed could

provide correct advice to mothers about what to do when their children get diarrhoea. The findings showed that health workers needed better training in clinical management

and on advising mothers. It prompted the CDD programme to establish four diarrhoea

training units (DTUs) at children's hospitals in the major centres - Hanoi, Hue and Ho Chi

Minh City. These units offer regular courses in clinical management of diarrhoea for

paediatricians working at provincial level. Later, four smaller DTUs were set up in large

towns to provide training for health workers in district hospitals. In addition,

courses for trainers about teaching health workers better communication skills have

started in six provinces. More household and health facility surveys were carried out in 1990-1991 to assess the

effectiveness of the DTU training programme. Use of ORS and ORT at home had increased by

around 500 per cent (to 35 per cent and 64 per cent respectively). Continued feeding and

continued breastfeeding had also risen markedly (to 76 per cent and 96 per cent

respectively). Hospital facilities also showed an impressive reduction in incorrect treatment practice

(drug use decreased to 57 per cent of cases and IV therapy to around 19 per cent). A

greater number (32 per cent) of health staff knew the correct advice to give to mothers. However, the surveys found there was still room for improvement, especially in more

remote areas, and in health workers' communication skills. Vietnam's experience shows how periodic evaluation can measure progress and identify

priorities for future action. Dr Nguyen Anh Dung, c/o National Institute of Hygiene and Epidemiology, 1 Yersin

Street, Hanoi, 10,000, Vietnam.

|

The selection of samples for surveys A survey is the systematic collection of information from individuals. It usually

involves asking questions face-to-face. The advantages of a survey are:

- It can provide information and statistics from a large number of people living in a wide

area.

- Many different pieces of information can be collected at the same time.

- If a sample is carefully chosen, information obtained from a few people can tell us

about a whole population.

How you choose a sample is crucial. Sampling means examining part of something in order

to learn more about the whole thing. For example, if you want to know how a pot of food

tastes you do not need to eat the whole pot, a spoonful will do.

There are two main types of sample:

Random sample - a 'chance' selection, in which all individuals or households

within an area being studied have an equal chance of being selected. For example, numbers

representing different households may be picked out of a box. When random clusters are

used, the initial household is chosen randomly, then a number of neighbouring households

are also studied. This method should produce a cross-section of the population under study

which can be analysed statistically.

Systematic sample - a simple way of choosing; for example, questioning every

tenth individual or those visiting a clinic on a particular day of the week. It can be a

quick way of selecting a cross-section of people; however, it may be open to bias .(e. g.

there may be special reasons why certain people attend on a particular day).

|

|

DDOnline

Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 51 December

1992  5 Page 6 7 5 Page 6 7

Taking a partnership approach

Marie-Thérèse Feuerstein describes an evaluation

process involving schoolchildren in India which was both educational and fun.

|

Flash cards test children's understanding of the link

between poor hygiene and diarrhoea. Health education talks are often given to children in primary schools. But what do the

children remember and how do they respond in practice?

|

A school health education evaluation package based on a child-to-child approach was

developed in India to test children's knowledge about health problems. The children had

been given health education lessons on a wide range of issues including nutrition,

diarrhoea and personal hygiene. Older pupils were chosen to work with an evaluation team of local health and community

workers. These pupils measured their younger schoolmates using a weight-by-height

measuring chart. They found that one in four younger children were only 60-80 per cent of

the correct weight for their height. This exercise reinforced earlier health education messages about the need to grow up

healthy and strong. It also helped teachers to identify underweight pupils who needed

extra attention. Health and community workers then used hand-drawn flash cards (see="#Flash card">box) to evaluate the children's understanding of three common

health problems: diarrhoea, scabies and eye infections. The diarrhoea flash cards showed:

- children buying sweets that were obviously contaminated

- the same children with diarrhoea

- and the children with diarrhoea drinking clean water.

The schoolchildren were asked questions about the connections between the pictures.

Half of them did not connect poor food hygiene and contaminated food with diarrhoea. The team presented the evaluation results to the teachers and children in the form of a

puppet show (see="#Feedback">box). The puppets were based on the flash card

characters so the story came to life. The children learned the correct answers to the

earlier questions through the puppets. The evaluation provided useful information for the

teachers about where children needed more knowledge. It also helped them to plan future

health education involving parents. Finally, it brought about the enthusiastic involvement

of pupils and teachers who asked for more evaluation! Dr Marie-Thérèse Feuerstein, 49 Hornton Street, London WS 7NT, UK.

Participatory evaluation Participatory evaluation means using local people to monitor and evaluate their own

progress. Instead of outsiders collecting information about communities, a participatory

approach involves the community in assessing how its health needs are being met. The value of this approach is in the learning experience of the participants, as well

as in providing information for people outside the community.

|

Flash card connections

Flash cards are a sequence of pictures telling a story. They are designed to trigger a

response in a viewer. Flash cards are often used to test viewers' understanding of the

connection between different events. They are useful because:

- they can be inexpensively produced locally

- they can be easily changed if field testing shows any misunderstandings about the

pictures

- they can tell stories that children understand and enjoy

- the viewers' response provides immediate feedback.

Feedback using puppets

Puppetry is a good way of providing feedback because:

- it is an active way to share evaluation results since puppets can have a dialogue with

the audience

- gaps in knowledge and practice can be taught in an enjoyable way

- puppets can act out private situations without offending or blaming the audience

- children who are shy talking to adults often talk freely to puppets.

|

Further reading Aarons A, 1988. Child to Child: an approach to learning

(revised and adapted for Indian schools). VHAI. Feuerstein M T, 1990. Partners in Evaluation. Macmillans. Available from TALC, 226

Hatfield Rd, St Albans, Herts AL1 4LW UK.

Gordon G, 1986. Puppets for Better Health: a manual for community workers and

teachers. Macmillans. Available from TALC.

|

|

DDOnline

Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 51 December

1992  6 Page 7 8 6 Page 7 8

Breastfeeding twins: double the benefits Margie Davies, a midwife and mother of twins, discusses

how to breastfeed twins. My twins, both boys, were born at 38½ weeks' gestation weighing 6lb 10oz and 6lb

5½oz, so I had none of the problems associated with feeding premature babies. But, as a

first time mother, I did have problems such as sore nipples, difficulties in attaching the

babies to the nipples (latching on), and not enough professional help at feed times while

in hospital. The midwives in hospital felt the best way to feed twins was together. From my own

experience and all that I had read, I agreed. However, putting it into practice was not so

easy. One baby latched on easily but tried to feed too quickly, so came off the breast

frequently as he could not cope with the fast flow of milk. His brother, on the other

hand, was difficult to fix on and quite sleepy during the feed, so required a lot of

stimulation to keep suckling. I needed at least two pairs of hands, and they were not

always available! The midwives were very good, but they nearly always got called away to

do something else during a feed, and you could guarantee it was after they left that I

would need the extra pair of hands. With all the on/off the breast and not getting the position quite right it is very easy

to develop sore nipples. They can very quickly become painfully cracked and bleed. If this

happens, it is easy to see how new mothers can be disillusioned and give up breastfeeding. We eventually settled into a routine of feeding the boys separately, as I had a back

problem and could not sit comfortably with both feeding together; but it took nearly six

weeks to arrive at this routine and for the sore nipples to heal. In the end my boys were

entirely breastfed for lO½ months. Once breastfeeding is established most mothers give each baby its own breast, as

supplies on each side are somewhat independent of one another so will develop to suit each

baby. If one baby is very small and does not have a very strong sucking reflex. it may be

necessary to swap the babies around in the first few days to make sure that both breasts

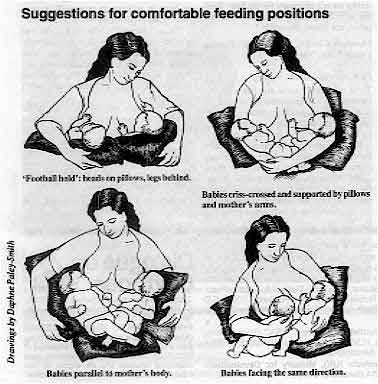

are sufficiently stimulated. Practical help on positions for feeding two babies together is required; there are

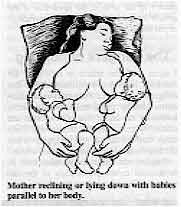

several possible feeding positions (see illustrations below). Suggestions for comfortable feeding positions

|

Clockwise, from top left: 'Football hold': heads on pillows, legs behind. Babies criss-crossed and supported by pillows and mother's arms. Babies parallel to mother's body. Babies facing the same direction.

|

Correction to positioning in breastfeeding twins picture

|

In one of the pictures, however, the positioning of the babies was not good

(see left). The babies' heads were turned away from their bodies, a position which makes

it difficult for a baby to get the breastmilk out of the breast. Poor positioning is also

a common cause of sore nipples. |

|

We asked our artist to redraw the picture (see left). Here, the babies look

comfortable, with their heads and bodies facing the mother. |

|

Mother reclining or lying down with babies parallel to her body. Midwives and health visitors in general need more education about the

problems of feeding twins and this should be included in their training. They

need to give the mother encouragement and confidence that it is possible to

breastfeed twins.

|

Margie Davies SRN, SCM, 11 Leppoc Road, Clapham, London SW4 9LS, UK. Support groups Multiple Births Foundation, Queen Charlotte's and Chelsea Hospital, Goldhawk Road,

London W6 0X6, UK. Twins and Multiple Births Association, PO Box 30, Little Sutton, L66 1TH, UK. Further reading Bryan E, 1992. Twins, Triplets and More - their nature, development and care.

Penguin, London, UK.

|

|

DDOnline

Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 51 December

1992  7 Page 8 7 Page 8

Jamaica's promotion of rehydration fluid I have read the article: 'We tell mothers to use ORS and they don't', published in DD48, with interest. I would like to clarify some of the points in

the article. The Ministry of Health's programme for control of diarrhoeal disease does not teach the

home preparation of ORS. ORS is used to treat dehydration and not for continual

home use. What are considered in the article as home remedies are the liquids taught by

the programme to be used at home to prevent dehydration. Therefore mothers are really

doing as instructed. ORS packets are available free at health centres and the access rate is over 90 per

cent. Diarrhoea accounts for less than 2 per cent of visits to health centres annually.

Therefore our programme for control of diarrhoeal disease is tailored to fit the

epidemiology of the disease in our country. Dr B Irons, Acting Senior Medical Officer, Ministry of Health, 10 Caledonia Avenue,

PO Box 472, Kingston, Jamaica.

DD would like to thank Dr Irons for drawing these points to our attention. We have

also passed on these comments to the author of the article. We apologise if the article

has caused any misunderstandings about the Ministry of Health's policy.

The dangers of purging I agree with the article in DD48 by Dr Jemima

Hayfron-Benjamin about the danger of purgatives. Purging is widely recommended by

traditional healers in Sierra Leone in the belief that all illnesses are caused by

problems with the bowels. They think that the illness will disappear when the bowels are

free of accumulated waste. Purging can cause dehydration and, in occasional cases, perforation of the intestines.

Oral purgatives, such as toxic plants, can poison the patient. Common oral purgatives in

this country include plant extracts which are usually used to make local soap or flavour

tobacco. Patrick Johnny, Dispensing Technician, Sonnie Pharmacy and Clinic, Njama-Kowa, via

Mano, Sierra Leone.

Exclusive breastfeeding... The articles on exclusive breastfeeding in DD49 prompted

extensive discussion at a monthly meeting of health workers in our area. These health workers said that they encourage the use of glucose water from birth until

three or four days later. Most workers believed that mothers' breastmilk was not available

until the third day after giving birth. Could I ask you to comment on that. Akekere Jonah, Assistant PHC Co-ordinator, Balga Health Zone, PO Box 66, Rivers

State, Nigeria.

... and extra drinks I am confused when you say that extra drinks are not necessary for the baby feeding

with breastmilk. My question is: are babies not thirsty like adults? Maureen Chioke, PO Box 305, Enugu, Enugu State, Nigeria.

Dr Katherine Elliott replies: These two letters show that our scientific knowledge about breastfeeding needs to be

more widely shared to promote exclusive breastfeeding as the ideal feeding practice for

the first four to six months of life. During pregnancy the breasts gradually become bigger and at birth they already contain

a special thick yellowish fluid, called colostrum. This is extremely valuable because it

is full of substances which protect the newborn against infections in its new environment

outside the womb. But colostrum does look very different from the thinner, bluish white

breastmilk which can take two to three days to appear. If the value of colostrum is not

well understood, people may believe babies should not be allowed to suckle until milk is

available in the breasts. Water, or other fluids, are often given instead. This belief

needs to change for at least three good reasons:

- The first few days after birth are the most dangerous time for babies. If they lose the

protection colostrum provides against infection at this critical time, this cannot be

replaced.

- Breastmilk is secreted by the breasts in response to the stimulus of sucking. The more

the baby sucks, the more the milk will flow. If babies are not put to the breast soon

after birth and allowed to suckle frequently, especially for the first week or two, the

breastmilk supply may never become properly established. As a result, weaning may have to

take place too early, before the baby has got a good start in life.

- As well as being the ideal food, breast-milk is safe and clean. With any other fluid,

there is always a risk of infection. Research has shown that infants receiving water, tea

or juice in addition to breastmilk have a much greater risk of diarrhoea and death.

There is no need to take this risk. Recent studies have shown that exclusively

breastfed babies do not require any extra fluids, even in hot, dry conditions. Giving

babies water means they may take less breastmilk, so they become less well nourished. Small babies are not thirsty, unlike adults. Babies just need frequent breastfeeding.

Babies who sleep with their mothers will sometimes feed as often as every half hour.

Mothers, however, often do feel very thirsty, especially in hot countries. They

need to drink more to keep up their breastmilk supply. For further reading see references="dd49.htm#page3">DD49 page 3 or write

to AHRTAG.

|

Scientific editors Dr Katherine Elliott and Dr William Cutting

Managing editor Kathy Attawell

Executive editor Kate O'Malley

Production Celia Till Editorial advisory group

Professor J Assi Adou (Ivory Coast)

Professor A G Billoo (Pakistan)

Professor David Candy (UK)

Dr Shanti Ghosh (India)

Dr Michael Gracey (Australia)

Dr Nicole Guérin (France)

Dr Norbert Hirschhorn (USA)

Dr Sharon Huttly (UK)

Dr Claudio Lanata (Peru)

Professor Leonardo Mata (Costa Rica)

Dr Jon Rohde (USA)

Dr Mike Rowland (UK)

Ms E O Sullesta (Philippines)

Professor Dang Duc Trach (Vietnam)

Professor Andrew Tomkins (UK) With support from AID (USA), Charity Projects (UK),

Ministry of

Development Cooperation (Netherlands), ODA (UK),

SIDA (Sweden), UNICEF, WHO Publishing partners

BRAC (Bangladesh)

CMAI (India)

CMU (China)

Grupo CID (USA)

HLMC (Nepal)

lmajics (Pakistan)

ORANA (Senegal)

RUHSA (India)

Consultants at University Eduardo Mondlane (Mozambique)

|

Issue no. 51 December 1992

Page Navigation

This edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online is produced by Rehydration Project. Dialogue on Diarrhoea was published four times a year in English, Chinese, French, Portuguese, Spanish, Tamil,

English/Urdu and Vietnamese and reached more than a quarter of a million readers worldwide. The English edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea was produced and distributed by Healthlink Worldwide. Healthlink Worldwide is committed to strengthening primary health care and

community-based rehabilitation in the South by maximising the use and impact

of information, providing training and resources, and actively supporting

the capacity building of partner organisations. - ISSN 0950-0235 Reproducing articles

Healthlink Worldwide encourages the reproduction of

articles in this newsletter for non-profit making and educational uses. Please

clearly credit Healthlink Worldwide as the source and, if possible, send us a copy of any uses made of the material.

|

updated: 23 August, 2019

|