|

| |

Issue no. 26 - September 1986

pdf

version of this

Issue version of this

Issue

|

There is much information in this issue that is valuable

and useful. Online readers are reminded, however, that treatment guidelines and health

care practices change over time. If you are in doubt, please refer to

WHO's up-to-date Dehydration Treatment

Plans.

|

Pages 1-8 Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online Issue 26 -

September 1986

|

DDOnline

Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 26 September 1986  Page 1 2

Page 1 2

Climate, customs and diarrhoea

Weather patterns have long been linked in people's minds with patterns of disease.

'Winter vomiting' and 'summer diarrhoea' were recognised as recurrent child health dangers

many years before scientists were in a position to explain why and how these infections

came about. Problems of seasonality

|

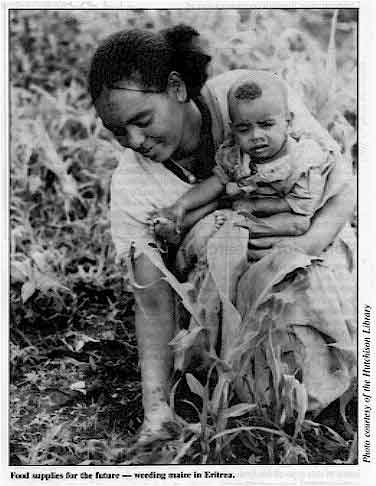

Food

supplies for the future - weeding maize in Eritrea.

In many parts of the world, people depend for their survival on rainfall which only

occurs at certain times. During the 'hungry season', when stores are running out, women

need to work extra hard in the fields to make sure the new crops benefit from precious

rains. Food supplies for the future are all important. In consequence, children and babies

suffer an increased risk of malnutrition and disease. Extremes of drought and of flooding

may make matters worse. Seasonal problems in The Gambia and in Bangladesh are described onpage three.

|

|

Value of behaviour change

People may not be able to change their weather but they can change their ways. Even

small alterations in the behaviour of mothers when handling their children will bring

about noticeable improvements (see="#page4">pages four and five).

The vital ORT message about how to prevent and treat dangerous dehydration due to

diarrhoea needs to be accompanied by appropriate family hygiene education, based on local

customs and circumstances (see="#page8">page 8). KME and WAMC

|

In this issue . . .

- Nasogastric feeding and rehydration

- The influence of climate, environment and behaviour on diarrhoea

|

|

DDOnline

Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 26 September 1986  1 Page 2 3 1 Page 2 3

|

Water handling and cholera The majority of those infected with the cholera vibrio are not seriously ill, and many

are symptomless carriers. The germ spreads rapidly in overcrowded or slum conditions.

Person-to-person transmission through contamination of domestic food and water seems to be

important. A study carried out in Calcutta, India, found that carriers of V. cholerae

were contaminating domestic water with their dirty fingers, where water was stored

in wide-mouthed vessels such as buckets.

| Two methods were used

to see if transmission of infection could be reduced: chlorination of stored water, and

the use of a narrow-necked earthenware vessel (called a sorai) for water storage.

|

|

These were tried out in similar population groups in east Calcutta. The results showed

that transmission rates of cholera were significantly reduced in both the group

chlorinating their water (by 57.8 per cent), and in the group using a sorai to store their

water (by 74.6 per cent). A third control group, who used neither method, showed no

reduction in transmission. These results also suggested that exposure to infection outside

the home was relatively less important than transmission within the home. The sorai has

the additional advantage of being cheap and also acceptable to the local community. Its

narrow neck prevents the introduction of infected hands and germs into the stored water.

Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 64 (1): 127-131,1986. Studies on

interventions to prevent El Tor cholera transmission in urban slums. B C Deb et al.

Reprints of this article are available from Dr Deb at the National Institute

of Cholera and Enteric Diseases, P-33, C.I.T Road, Scheme XM, Beliaghata, Calcutta, 700

010, India.

|

Money for research

Funds will be available from WHO in 1987 to support biomedical and epidemiological

research in diarrhoeal disease control in the following areas: epidemiology and disease

prevention; immunology, microbiology, and vaccine development; case management. Applicants

wishing to apply for support should send 1-2 pages outlining the proposed project to the Research

Co-ordinator, CDD Programme, 1211 Geneva 27 Switzerland. Preference will be given to

projects of the most direct relevance to the problem of childhood diarrhoea in developing

countries. In addition, support is available for health services research, both operational and

applied research linked to national CDD activities. Those interested in this type of study

should write to their WHO regional office. Coconut water for rehydration?

Is water from unripe coconuts suitable for rehydration of children with acute

diarrhoea? In Tanzania, it is a popular drink and the Tanzanian National Diarrhoeal

Diseases Control Campaign has recently analysed it to see if it could be safely

recommended for rehydration. Compared to the WHO-recommended ORS formula, it is low in

sodium, chloride and bicarbonate but also contains a higher concentration of glucose,

potassium, magnesium and calcium. The amounts vary depending on whether the coconuts have

been harvested from coastal or inland areas. Coconut water is therefore not recommended as an alternative to ORS for rehydration.

Mothers in Tanzania have proved that they can, with proper teaching, prepare a safe and

effective salt and sugar solution at home for early treatment of diarrhoea in

children.* Porridge made from maize or millet flour is the main weaning diet for

most children, and, like rice-ORS in Bangladesh, may form the basis for a future

cereal-based ORS in Tanzania. Dr Abel Msengi, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Faculty of Medicine, P.

O. Box 65001, Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania. *Editors' note: Where sugar-salt solution cannot be easily made, coconut water

may be a useful, clean drink in the very early stages of diarrhoea, before any dehydration

occurs. Further reading

1. Msengi A E et al, 1985. The biochemistry of water from unripe coconuts obtained

from two localities in Tanzania. E Afr. Med J. 62 (10); 725. ORS production

The revised WHO manual ORAL REHYDRATION SALTS - Planning, establishment and

operation of production facilities, mentioned in DD 23, is

now available in French. A Spanish edition will be available soon. Readers should write to

Mr Hans Faust, CDD Programme, WHO, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland. Many countries have now set up facilities for local production of ORS. For example, in

Nigeria, WHO and UNICEF have provided technical expertise to a private company,

ASTRA-AREWA, to set up production of oral rehydration salts packets. The ORHESAL packets

have been designed to make up 600 ml of oral rehydration solution, using the standard

sized containers widely available in Nigeria: a 600 ml beer bottle or two 300 ml mineral

bottles. Stickers, posters and prescription pads for doctors promote the use of ORS for

dehydration. The current annual production of 2 million packets of ORHESAL is

expected to increase to 6 million in 1987. Breastfeeding - a new book

Breastfeeding for Modern Mothers is a practical, helpful paperback by

Dr Clair Isbister. It is well illustrated and costs $5.95 Australian from Hodder and

Stoughton (Australia) Pty Limited, 2, Apollo Place, Lane Cove, NSW 2066, Australia. Erratum

Maureen Minchin tells us that Breastfeeding Matters is available from: 5

Meredith Court, Alfredton, Victoria 3350, Australia, not the address given in DD 24. US $, sterling and other currencies are acceptable as well

as Australian $. The price of $12 Australian can be reduced for readers unable to pay the

full cost. The author is willing to exchange the book for other publications.

|

|

DDOnline

Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online Issue 26 September 1986  2 Page 3 4 2 Page 3 4

| The seasons and diarrhoea |

The Gambia and Bangladesh

Seasonal variations in rainfall and temperature often bring changes in disease

patterns, especially diarrhoea. Very little is known about why this happens and patterns

may change from one year to the next. Mike Rowland discusses

seasonality and diarrhoea in The Gambia and Bangladesh.

|

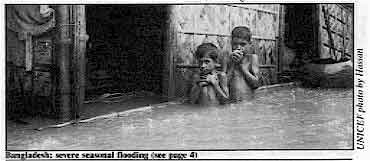

Bangladesh: severe seasonal flooding The Gambia and Bangladesh share some common characteristics in climate including a cool

dry winter of three months followed by a hot dry spring, and hot wet summers of five to

seven months in length. The main difference is in the amount of rainfall. While The Gambia

may have 20-30 inches of rain per year, Bangladesh usually has up to four or five times

this amount.

|

|

Drought is a recurring problem in The Gambia, floods in Bangladesh. These climatic

factors have an important impact on the incidence of diarrhoeal disease. A study in The

Gambia found there was a close link between the time of the annual peak in diarrhoea in

young children and the summer rains. A second peak of diarrhoea in the winter was also

significant and was shown to coincide with a short period of intense transmission of

rotavirus. The agents Of the enteric infections of childhood, the enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC),

that is, those producing heat-stable toxin (ST), were found to be the most important

aetiological agents of diarrhoea in both countries, with a peak during the rains. ETEC are

thought to be transmitted mainly by food and water. In rural Gambia, water is obtained

almost exclusively from surface wells, 15 to 20 metres deep. It was found that, although

this water was faecally contaminated throughout the year, levels of contamination

increased by up to one hundred times within one or two days of the start of the rains

because excreta is washed into the wells. It was also clear that contaminated water and

domestic environment contribute to contamination of children's food. The high level of

contamination of food during the summer coincided with the time of high diarrhoea

prevalence. In Bangladesh it was shown that the incidence of ETEC diarrhoea in infants was

positively correlated with the frequency of consumption of weaning foods contaminated with

faecal coliforms. The seasonal peak of ETEC diarrhoea coincided with the time when food

was most contaminated due to higher bacterial growth caused by high temperatures. Cholera is endemic in many areas of Bangladesh but not in The Gambia. Though similar to

some other diarrhoeal diseases in showing a rainy season peak, the timing of peaks of

cholera incidence can and has changed from year to year in Bangladesh. The reason for this

and the variable occurrence of a less marked pre-rains peak of cholera is not known. A

similar pattern, with twice yearly peaks in incidence occurs with shigellosis, an

important disease in both countries, particularly Bangladesh where the more virulent

species predominate and are becoming rapidly resistant to routinely used

antimicrobials.

It has been suggested that diarrhoea epidemics occurring in the post-rains period might be

due to increasing concentrations of faecal organisms in dwindling water supplies, but a

study of village wells in The Gambia produced no evidence to support this. Social and economic factors In both Bangladesh and The Gambia women's' work is important in the rural farming

economy. During the main farming season, therefore, busy mothers have less time for

breastfeeding. In Bangladesh, for example, suckling time has been shown to be less, and in

The Gambia intervals between feeds are longer; children might even be prematurely weaned.

Smaller amounts of breastmilk were consumed by breastfeeding infants at this time of year

coinciding with poorer maternal nutritional status. This was also the season of poorest

nutritional status in children, leading to increased duration, and perhaps severity, of

diarrhoea. Personal hygiene, attitudes to breastfeeding, and weaning practices are important

factors in diarrhoeal diseases all year round, whatever the season. To be more effective,

health education messages could be varied according to the season, as different problems

occur at various times of the year. In a recent Mass Media for Infant Health Campaign in

The Gambia, the emphasis changed from nutritional to rehydration strategies at different

times. Changing the emphasis could help to offset the impact of the seasonal factors which

cause very high death rates from diarrhoea at certain times of the year. Dr M. G. M. Rowland, Associate Director, ICDDR, B, GPO Box 128, Dhaka 2,

Bangladesh. Further reading Seasonal Dimensions to Rural Poverty, 1981. Chambers R, Longhurst R, Pacey A, eds.

London: Frances Pinter (Publishers) Ltd. Diarrhoea and Malnutrition: Interactions, Mechanisms and Interventions, 1982. Chen

LC, Scrimshaw NS, eds. New York: Plenum Publishing Corporation. Mass Media and Health Practices. Field Notes, 1984. Offices of Education and Health,

Academy for Educational Development, Washington DC.

|

|

DDOnline

Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online Issue 26 September 1986

3 Page 4 5 3 Page 4 5

| Environment, behaviour and the spread of diarrhoea |

A vulnerable age

A study in Bangladesh discovered high rates of diarrhoea in crawling infants. The

results and a range of interventions to help protect this age group are described in this

article. Diarrhoea occurs most often in Bangladesh in children between the ages of six and

eleven months - the time when they start to crawl. In rural areas, crawling infants come

into contact with chicken faeces and other animal dung on the ground inside and outside

the home. The ground is also contaminated with the baby's own faeces and those of its

brothers and sisters. Many infants put earth and faeces in their mouths and most suck

their fingers which have touched and will pass on germs and faecal matter. Infants in two villages near Dhaka were found to have high rates of illness and

malnutrition. Those whose families were poor and did not own land were more severely

affected - they had worse malnutrition and a higher incidence of diarrhoea. One village

suffered from severe seasonal flooding, contaminating the environment and probably

contributing to a very high diarrhoea rate. Crawling behaviour and environment In both villages most infants were put down to play for most of the day. In one village

nearly half the infants were down all day, and a further 23 per cent every morning and

afternoon. In the other, nearly 90 per cent were put down to play either all day or every

morning and afternoon. Fewer than 2 per cent of infants in both villages were put down to

play on the ground less than once a day. Most mothers said they rarely or never put a mat

or jute sack down for their baby to lie on or crawl around on, and only a third of mothers

were able to watch their babies continuously. The ground on which these infants were crawling was found to be highly contaminated.

Some sort of animal dung or faeces (usually chicken faeces) were found in 91 per cent of

play areas in one village, and in 70 per cent of play areas in the other. Half the mothers

had also seen their babies eating or touching faeces during the previous two weeks. Traditional beliefs

It was discovered that while most mothers knew that faeces were dirty, they were not

aware that faeces can cause disease. Hence they do not see the need to keep their homes

and yards clear of faeces and do not know that they are exposing their children to germs.

In fact most mothers bathed their babies every day to keep them clean. Poor traditional

weaning practices and poor food hygiene also contributed to high attack rates of

diarrhoea. Interventions and health education

Basic messages and a range of interventions to improve traditional hygiene and child

care practices were developed. Firstly, mothers needed to understand about germs, and the

fact that these cause diseases such as diarrhoea, even though they cannot be seen. Local

materials and ideas were used to demonstrate this to a mainly illiterate audience. Mothers

already knew that fishermen use alum crystals to purify river water for drinking. Alum

crystals were mixed with a glass of pond or river water that looked clean, but was not

free from germs. The dark coloured sediment that collected at the bottom of the glass was

explained to mothers as the bodies of tiny dead germs 'smaller than chicken lice' killed

by the alum. To show that germs stay on the hands and are passed on after washing with

just water, the mothers' hands were rubbed with red magenta make-up powder. Even after

washing, mothers could see that they still left a red handprint on their babies or any

household objects they touched. Interventions to keep the baby from touching and eating faeces:

- Sweeping the baby's play area four times a day. All households possessed a broom made of

stiff straw. Messages emphasised that brooms keep away germs and keep homes beautiful.

- Using a dirt disposer, like a trowel, or a farming hoe to remove faeces from the ground.

The dirt disposer was adapted from the hoe, made in the local bazaar and was popular with

villagers because they could remove faeces without soiling their hands.

- Using a covered pit or latrine to dispose of faeces.

- Using a special place for disposing of garbage.

- Keeping crawling infants in a playpen instead of letting them play freely on the ground.

Inexpensive locally made playpens of bamboo, jute and nylon kept the infants off the

ground, and could be easily cleaned. Mothers liked the playpens because they could get on

with their work and know their babies were safe.

Interventions to reduce transmission of germs:

- Washing hands with ashes or soap after defaecating (most households could not afford

soap but ashes were available and acceptable).

- Handling the water carrier (used for washing after defaecation) with the right hand so

that germs from the left hand do not contaminate the carrier for other users.

- Cutting the fingernails of all family members with a blade every week. (This helps to

prevent transmission of germs to the mouth as it is customary in Bangladesh to eat with

the hands.)

- Washing babies in a particular place after defaecation so that germ-contaminated water

does not spread everywhere.

Interventions to reduce transmission of germs during weaning:

- Keeping food covered to protect from flies, dirt, chickens and dogs.

- Storing clean plates and pots and pans upside down or covering them.

- Washing hands and plates with tubewell water before eating.

- Using only tubewell water for drinking and for mixing food for the baby.

Taken from Sanitary Conditions of Crawling Infants in Rural Bangladesh by

Marian E Zeitlin, Georgia Guldan, Robert E. Klein and Nasar Ahmad, with the collaboration

of Kamal Ahmad, and; Messages and Interventions for Social Marketing from A Village

Trial Laboratory for Developing Diarrhoeal Disease Control Behaviours by Marian F.

Zeitlin, Azmat Ara Ahmad, Nasar Ahmad, Georgia Guldan and Suaib Ahmed.

|

|

DDOnline

Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 26 September 1986  4 Page 5 6 4 Page 5 6

| Environment, behaviour and the spread of diarrhoea |

Soiled saris

Clothes can act as carriers of disease. Bonita Stanton

and John Clemens look at how the sari may spread diarrhoeal

infections.

Saris are worn by most women in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh and fairly widely

throughout the rest of Asia. The authors noticed that Bangladeshi women in slum areas of

Dhaka often used their saris for many household tasks as well as for clothing purposes. A

study was carried out to see whether this behaviour was common and if it affected the

rates of childhood diarrhoea.

Collecting data

|

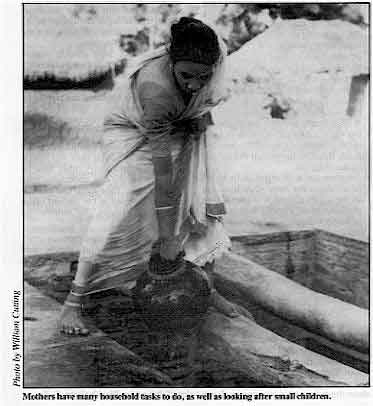

Mothers have many household tasks to do, as well as

looking after small children. Information was obtained from 247 families in Dhaka slum areas about the sex and age of

children under six; family income; maternal education; and attitudes of mothers towards

'misuse' of saris. Mothers were observed at home to learn about their usual hygienic

practices, including what they did with their saris. Information was also collected on the

incidence of diarrhoea among their children. Contamination of saris There was no practice that all mothers believed to be a wrong use of the sari,

including wiping a child's bottom after it had defaecated. Very few suggested that a

particular use 'can spread disease'. Misuse of saris was seen as wrong for other reasons.

such as 'it will make the sari wet'.

|

Altering behaviour

Discussion with mothers clearly showed that the women were not aware they were

contaminating their saris, or that the soiled saris could pass on diseases like diarrhoea

to their children. It is important to convince them of this danger, because they can

easily change their own behaviour and see results for themselves, unlike many other

hygiene interventions. Success in preventing misuse of saris could serve as a good

indicator to health workers of the effectiveness of an educational message in altering

behaviour in a sanitation programme. Also, as general hygiene conditions improve, personal

hygiene practices such as misuse of saris will become even more important. Bonita Stanton, Director, Urban Volunteer Program, and John Clemens, Scientist,

ICDDR, B, GPO 128, Dhaka 2, Bangladesh.

|

|

DDOnline

Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 26 September 1986  5 Page 6 7 5 Page 6 7

Using a nasogastric tube

Christine Candy describes the practical issues involved. Where possible, oral rehydration solution and food should be given by mouth. A

nasogastric tube is useful when children are unable to drink safely and in sufficient

amounts for any of the following reasons: severe dehydration; if IV therapy is

unavailable; low birth weight infants; or the child is drowsy or vomiting. Severely

malnourished children may be fed initially in this way if they are too weak or anorexic to

eat or drink normally. It is therefore important that health workers know how to use

nasogastric tubes.

|

Equipment The health worker will need the following:

- Nasogastric tube. A 6 french gauge tube with an internal diameter of 1.4mm, or an 8

french gauge tube with an internal diameter of 1.8mm, is usually suitable. Check that

fluid will flow easily down the tube, before passing it down. (If proper nasogastric tubes

are not available, polythene/nylon tubes of the right size can be used, provided they are

clean, rinsed and have no rough edges.)

- Lubricating fluid such as: 'KY Jelly' or Vaseline if available; water; or mothers'

saliva, if working in field conditions.

- Syringe (20 ml or 50 ml). This can be used afterwards as a funnel for giving feeds.

- Blue litmus paper, if available.

- Adhesive tape.

- Stethoscope if available.

- Fluid to be given.

|

Method

- Explain to the child's parents and the child, if old enough to understand, what you are

going to do.

- Lie infants flat. Lie unconscious patients on their sides to avoid aspiration (the

regurgitation and inhalation of fluid into the lungs). Older children may prefer to sit

up.

- Measure the approximate length from the child's nostril to the ear lobe and then to the

top of the abdomen (just below the ribs) with the tube, and mark the position. This will

be a guide to how far to insert the tube.

- Clean the nostrils to remove mucus. Lubricate the tip of the tube and gently insert into

the nostril. Pass the tube down through the nose slowly and smoothly. Stop if the child

gags (retches or chokes) and see if the tube is coiled in the mouth. If it is, gently pull

out the tube and try again.

- If the child is conscious, give a drink of water. This helps to pass the tube down

towards the stomach and reduces discomfort.

- If the child coughs, the tube may be going into the trachea (windpipe) - pull it out

gently and try again. NB. A child who is partly or completely unconscious, may not have a

cough reflex and the tube could go down the trachea without causing coughing. Always watch

for cyanosis (blue lips and tongue) and distressed breathing. These may be the only signs

in an unconscious patient that the tube is entering the lungs.

- Continue to pass the tube down until the position marked reaches the nostril. The end of

the tube should then be in the stomach. Check once again for choking, restlessness or

cyanosis. Fix the rest of the tube with adhesive tape below the nose and to the cheek or

side of the forehead.

- To check that the tube is in the stomach, use the syringe to suck up some fluid and test

with blue litmus paper. If the colour changes from blue to red the tube is in the stomach.

If blue litmus paper is not available, but the fluid sucked up is clear, containing mucus

or partially digested food, this also shows that the tube is in the stomach.

- Another test is to inject 20 to 50 ml of air down the tube while listening to the upper

abdomen, either with a stethoscope or directly with the ear. A distinct gurgle will be

heard as air enters the stomach. (This will not be heard if the tube is in the lung).

- If satisfied the tube is in the correct position, inject 5 to 10 ml of fluid (saline or

OR solution, not milk formula) by syringe, and again look for choking or cyanosis.

Rehydration and feeding

Where possible, give a continuous drip of fluid. If this is not possible, give frequent

small amounts using the syringe as a funnel. Hold the syringe upright, about 30 cms above

the child's head, for a slow and gentle flow. After each feed, close the tube with a

stopper or clamp and note amount given. Before each feed (or every four hours in

continuous feeding), look into the mouth to make sure the tube has not come out of the

stomach into the throat. Suck up a little fluid and check as before. Children who are able to drink will normally refuse ORS once rehydration is complete

and they are no longer thirsty. However, in nasogastric feeding, the normal thirst

mechanism is bypassed and it is possible to give too much fluid. It is therefore important

to stop giving ORS by nasogastric tube as soon as the child is able to drink normally or

is fully rehydrated. Overhydration can be dangerous. Prolonged nasogastric feeding If feeding continues for more than 24 hours, do the following:

- Clean the nostrils with warm water every day, especially around the tube. Change the

tube to the other nostril every few days. Keep the mouth very clean with a dilute solution

of 8 per cent sodium bicarbonate, if available, or citrus fruit juice. This helps to keep

the saliva flowing and prevents infections.

- Wet adhesive tape quickly makes skin sore. Take off damp tape with plaster remover or

ether. Clean skin with water and dry thoroughly. Change the position of the tape from time

to time.

Stopping nasogastric feeding If feeding has been continuous, start by changing to hourly then two hourly feeds. Then

give every other feed by mouth during the day, continuing tube feeds at night. Tube feeds

can then be gradually stopped as the amount taken by mouth increases. To remove the tube:

- Remove the adhesive tape.

- Take the tube out gently and smoothly. (Older children may prefer to remove it

themselves).

- Offer the child a drink and gently cleanse the nostrils.

After prolonged nasogastric feeding a child may have feeding problems or loss of

appetite. Patience and encouragement are needed to establish feeding by mouth again. Christie Candy, Paediatric Nurse Tutor, Queen Elizabeth School of Nursing,

Edgbaston, Birmingham, U. K.

|

|

DDOnline

Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 26 September 1986

6 Page 7 8 6 Page 7 8

An ORT centre in Malawi

Dr Mbvundula describes the impact of an ORT training

centre at the Kamuzu Central Hospital in Lilongwe. The CDD programme in Malawi became fully operational during 1985, when oral rehydration

therapy (ORT) units were set up in all hospital out-patient departments, and ORT was

integrated into the activities of all health facilities. Before this, an ORT training

centre had been established in July 1984 at the Kamuzu Central Hospital out-patient

department in Lilongwe. During the next five years, the national CDD programme plan hopes

to be able to meet the following targets:

- offer effective out-patient and in-patient diarrhoeal disease treatment;

- educate mothers about ORT,

- decrease hospital admissions from diarrhoeal diseases;

- decrease hospital case fatality rates from diarrhoeal diseases.

The ORT Centre The Kamuzu Central Hospital (KCH) is the main referral centre for the Central and

Northern regions of Malawi, and has a paediatric ward with 97 beds. The occupancy rate of

the ward is around 200 per cent all year round, with many children sharing beds. The

greatest number of admissions to the ward occurs between December and May, coinciding with

the peak season of diarrhoeal diseases. Between 1981 and 1983, approximately seven per cent of admissions to the paediatric

ward were for diarrhoeal diseases. Of children hospitalised with diarrhoeal disease during

this period five per cent died. Impact of activities

|

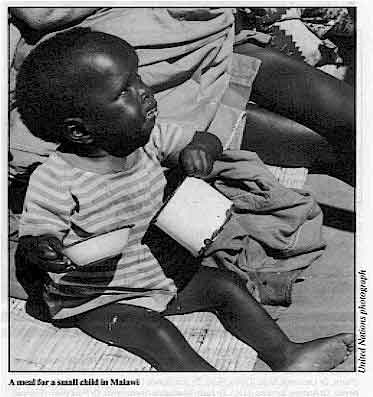

A meal for a small child in Malawi

An evaluation of the ORT Centre after one year showed that:

- A total of 1,711 children had been treated, of whom 35 (two per cent) were admitted as

in-patients.

- Seventy-five per cent of these children had diarrhoea alone, the rest had diarrhoea in

combination with other illnesses such as malaria and acute otitis media. (Children with

measles are admitted directly to the paediatric ward to avoid spreading the disease in the

ORT Centre. Therefore measles associated with diarrhoea was rarely seen at the ORT

Centre.)

|

|

- Of the children treated at the ORT Centre: 62 per cent were aged 0-12 months; 26 per

cent were aged between 13 and 24 months; and 12 per cent were over 24 months of age.

- Admissions to the paediatric ward decreased by 40 per cent compared to figures for

1981-1983.

- The case fatality rates for the paediatric ward did not change, perhaps due to the fact

that only severely ill children were admitted - milder cases being treated in the ORT

Centre.

National hospital reporting during 1985 showed a decrease in admissions due to

diarrhoeal disease throughout Malawi, and this is probably the result of the establishment

of ORT units in all health facilities in the country. Dr Mbvundula, Chief Paediatrician and Chairman, CDD Committee, Ministry of Health,

Kamuzu Central Hospital, P. O. Box 149, Lilongwe, Malawi. Editors' note: WHO has recently published a manual entitled: Diarrhoea

Training Unit-Director's Guide. It contains useful information on setting up and

running a diarrhoea training unit. Copies are available free of charge from the Director,

Diarrhoeal Diseases Control Programme, WHO, 1211 Geneva 27 Switzerland.

|

|

DDOnline

Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 26 September 1986  7 Page 8 7 Page 8

ORS composition

I am receiving DD regularly. Thanks for the valuable information. I use it for

the teaching of health workers who only know 'Farsi' language. We are using ORS with

satisfactory results in terms of tolerance, and response. I wish to know your opinion

regarding the composition of the ORS packet enclosed. Dr Gopal P. Gupta, PO Box 458, Sanandaj, Iran.

Editors' note: Thank you for your letter to DD enclosing the oral electrolyte

packet (Pursina) which you are currently using in Iran. As you can see from the comparison

table below, the Pursina solution is deficient in sodium and chloride for severe secretory

diarrhoea. It also contains rather too much glucose which could hold fluid in the gut

lumen by osmotic tension. The trace elements are not necessary if children are receiving

milk or other food, which is the WHO recommendation as soon as initial rehydration is

completed within 2-4 hours. The solution will, however, probably be of some value in

milder cases.

Rehydration solutions (comparison in

mmol/l) |

| |

ORS solution

WHO/UNICEF |

|

OraI Electrolyte

(Pursina) |

| Bicarbonate |

Citrate |

|

| Sodium |

90 |

90 |

30 |

| Potassium |

20 |

20 |

25 |

| Chloride |

80 |

80 |

25 |

| Citrate |

- |

10 |

25 |

| Bicarbonate |

30 |

- |

- |

| Glucose |

111 |

111 |

194 |

| Sulfate |

- |

- |

4 |

| Magnesium |

- |

- |

4 |

| Phosphate |

- |

- |

5 |

| Calcium |

- |

- |

4 |

| Saccharin |

- |

- |

(10 mg) |

Taste and temperature

Since UNICEF introduced ORS packets in Pakistan a few years ago, we have been using and

promoting ORT. I have observed that sometimes children refuse to take it. Probably because

commercial packets of ORS are widely available in Pakistan, homemade ORS is not popular.

(However, I do not think ORS packets would be available in remote areas of Pakistan, and I

do not think people there know how to prepare ORS at home either). One pharmaceutical

company has made orange-flavoured ORS. That too is often refused by children. I feel it is

because of the TASTE of the solution and also the TEMPERATURE of the water added. Here in

towns and cities, children, unlike those in the villages, are used to cold water. My

mother tried to give my child ORS with a little ice in it. It was very well accepted. I

agree it is costly for people in the villages to use ice, but wherever we can find ice

prepared from boiled water, we tell the parents to add it to ORS. Do you agree? Do you

think orange-flavoured ORS is technically sound?

Dr (Capt.) Mohammed Asif, Director General, Gulshan Hospital, A-2/3 Gulshan e-Iqhal,

Karachi, Pakistan.

Editors' note: One important symptom of dehydration is thirst. Because they

are thirsty, most dehydrated children will accept ORS readily, even if it is unflavoured

and given at room temperature. Refusal to accept ORT usually means dehydration has been

corrected or is quite mild. Some children, especially those over two years and with only

mild dehydration, may accept flavoured or cooled solutions more readily, but it is not

certain that this has much practical importance; moreover, the possibility of excessive

intake should also be considered. See See="dd22.htm">DD 22 for

practical hints on giving ORT.

Hygiene outside the home

We are currently implementing an educational program for rural mothers with children of

five years or less in the areas of oral rehydration therapy and child growth monitoring.

In developing educational materials, investigation and subsequent testing of materials, we

have encountered a real difficulty. Mothers and children spend a large portion of their time in the fields - often long

distances from their homes. This means that they are working and eating almost every day

with little or no access to water, outhouse or any type of sanitation facilities.

Promoting good hygiene is a primary concern of ORT/CGM. This, however, becomes a major

obstacle when the 'target' group spends such a large portion of time working in the

countryside where they have to prepare food and feed young children. As you well know, the

classic educational materials for ORT etc. demonstrate hygienic practices in the home,

with sufficient water, bowls, soap, heating facilities and so on. This is not the Bolivian

reality, nor do we think it is the reality in most developing countries. We are concerned

about how this problem can be dealt with effectively and would like any suggestions or

ideas you may have. Certainly there are no easy answers but, based on the world-wide DD

readership, we would be very interested in your response to this problem.

Curt Schaeffer, PRITECH Representative, and Dra. Ana Maria Aguilar, Consultant to

PRITECH, La Paz, Bolivia.

Editors' note: Several actions could help overcome these problems. For

example, special areas for defaecating well away from any water source, play areas or

places where people rest or eat. Even cleaning and rubbing hands with grass, soil, sand or

leaves after defaecating and before handling food, and keeping fingernails short, can

help. Cover food to protect against flies and, where possible, reheat thoroughly before

eating. The Editors would welcome suggestions from DD readers with experience of similar

problems, for publication in a future issue.

|

| In the next issue . . .

DD 27 will look again

at the role of parasites in diarrhoea |

Scientific editors Dr Katherine Elliott and Dr William Cutting

Editor Kathy Attawell

Editorial assistant Maria Spyrou Editorial advisory group

Professor David Candy (UK)

Professor Richard Feachem (UK)

Dr Shanti Ghosh (India)

Dr Michael Gracey (Australia)

Dr Norbert Hirschhorn (USA)

Dr Claudio Lanata (Peru)

Professor Leonardo Mata (Costa Rica)

Dr Jon Rohde (USA)

Ms E O Sullesta (Philippines)

Professor Andrew Tomkins (UK)

Dr Ruth Tshabalala (Swaziland)

Dr Paul Vesin (France)

Dr M K Were (Kenya) With support from AID (USA), ODA (UK), UNICEF, WHO and GTZ

|

Issue no. 26 September 1986

Page Navigation

This edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online is produced by Rehydration Project. Dialogue on Diarrhoea was published four times a year in English, Chinese, French, Portuguese, Spanish, Tamil,

English/Urdu and Vietnamese and reached more than a quarter of a million readers worldwide. The English edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea was produced and distributed by Healthlink Worldwide. Healthlink Worldwide is committed to strengthening primary health care and

community-based rehabilitation in the South by maximising the use and impact

of information, providing training and resources, and actively supporting

the capacity building of partner organisations. - ISSN 0950-0235 Reproducing articles

Healthlink Worldwide encourages the reproduction of

articles in this newsletter for non-profit making and educational uses. Please

clearly credit Healthlink Worldwide as the source and, if possible, send us a copy of any uses made of the material.

|

updated: 23 August, 2019

updated: 23 August, 2019

|