|

| |

Issue no. 41 - June 1990

pdf

version of this

Issue version of this

Issue

|

There is much information in this issue that is valuable

and useful. Online readers are reminded, however, that treatment guidelines and health

care practices change over time. If you are in doubt, please refer to

WHO's up-to-date Dehydration Treatment

Plans.

|

updated: 24 April, 2014

Pages 1-8 Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online Issue 41 - June 1990

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 41 June 1990

Page 1 2

Page 1 2

ORT today and tomorrow

Infant and young child mortality could be greatly reduced if people used oral

rehydration therapy correctly and often enough. DD, celebrating ten years of

publication with this issue, has always reported on efforts to prevent and treat

diarrhoeal diseases. Promotion of ORT has been one of the main functions of the

newsletter. Global production of ORS is now more than 350 million packets a year, and access to OR

therapy has increased considerably in the last decade. At the same time, CDD programmes at

all levels have made great progress in spreading messages about interventions which can

prevent diarrhoeal diseases. More and more families and health workers have learned to use ORT, and many deaths have

been averted. It has also become increasingly clear that giving home fluids early to

prevent dehydration and continuing to give nutritious foods is the best way to prevent a

case of diarrhoea from becoming serious. Still much to be done Despite these efforts, four million children a year still die from diarrhoea. ORS

packets are not available to every child in need of treatment for dehydration. Families in

remote areas may not be able to obtain the packets, and poor families may not be able to

pay for them. In addition, while standard ORS treats dehydration effectively and safely, it does not

stop the diarrhoea, which is almost always the first concern of mothers. For this reason,

some health professionals and families still remain unconvinced about the benefits of ORS,

and tend to give dangerous and ineffective drugs. Recent research suggests that cereal

based ORS formulations reduce stool volume and duration of illness (see="#page4">pages

4 and 5). Therefore, cereal ORS could be promoted as having an

anti-diarrhoeal effect, which might lead to reduced use of inappropriate drugs. Home management Most cases of acute diarrhoea, if handled properly and early enough at home, will not

require treatment with ORS. Home management should be based on giving extra amounts of

safe fluids together with continued feeding with the child's normal diet.

|

To treat diarrhoea at home, give extra fluids and

continue giving nutritious foods. The choice of home fluids will depend on local circumstances. In some areas, sugar-salt

solutions have been used successfully, but in others there have been problems with

dangerous and ineffective solutions caused by incorrect mixing.

|

|

Similarly, cereal-salt solutions have advantages and disadvantages. If made with local

staple foods, they are cheap, easily available, culturally acceptable and more likely to

be given earlier in the illness. Also, there is no risk of the osmotic diarrhoea

associated with solutions made with too much sugar. If too much cereal is added to an oral

rehydration solution, it becomes too thick to drink. However, it is most important that

cereal based ORT solutions are not confused with food, and that mothers do not dilute the

child's usual foods to make home fluids (For the latest guidelines from the World Health

Organization on the selection of home fluids, see="#page2">page 2). KME, WAMC and KA

|

In this issue:

- Home fluids for diarrhoea

- Cereal based ORT - research reports

- Practical advice on cup feeding

- Potassium - questions and answers

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 41 June 1990

1 Page 2 3 1 Page 2 3

Selection of home fluids Home treatment of acute diarrhoea should:

- prevent dehydration by giving increased fluids; and

- maintain nutrition by continuing to breastfeed or by giving acceptable, nutritious

foods.

ORS solution made from a packet of oral rehydration salts is designed to treat

dehydration, but can also be used to prevent it. Where ORS is not available, other fluids

should be used to prevent dehydration. Fluids recommended, in addition to

breastmilk,

include:

- sugar-salt solutions

- food based fluids, such as cereal gruels or soups

- plain fluids such as water or weak teas without sugar.

Sugar-salt solutions

Experience in many countries has shown that families may be unable to make special

fluids correctly. Some ingredients may not be available; it may not be possible to carry

out the careful measuring needed; or the recipe may be forgotten over time. Sugar-salt

solutions (SSS) made with too much salt or sugar are potentially dangerous for young

infants. Also it has been found that many families view SSS as 'medicine', and so too

little fluid is often given too late. Food-salt solutions Food-salt solutions could provide an alternative to SSS. They can be made from ordinary

ingredients and might be more likely to be given in larger amounts. Food-salt solutions

could include commonly available fluids looked on as drinks, which are familiar, easy to

prepare and acceptable for giving to children with diarrhoea. Such drinks include food

based fluids which contain cooked starch and protein, such as cereal soup or porridge. The

addition of salt (up to 3g/l) would increase their effectiveness for ORT. Food-salt

solutions may also promote sodium absorption more effectively than sugar-salt solutions

because they contain more of the carrier molecules (glucose and amino acids derived from

starch and protein) necessary for water and salt absorption in the gut. This means that

food-salt solutions may decrease stool output and reduce losses of salt and water. Whether or not mothers should be encouraged to add salt to food based fluids will

depend on the amount of salt usually included in food for children, and the feasibility of

teaching mothers to add the right amount of salt. If food based fluids are recommended for diarrhoea, it is important that families do

not confuse fluids for rehydration with food, and that children with diarrhoea are given

enough to eat. It is not recommended that children be given watered down versions of

thicker foods which are part of the normal diet. Food based fluids should be given in

their usual form, except for the addition of salt if this is necessary. Messages about

appropriate feeding as well as giving suitable fluids should continue. Familiar drinks Another approach is to promote drinks which are familiar and commonly available, but

which contain no added salt and relatively little starch or protein. These include weak

cereal solutions such as rice water, water in which other cereals have been cooked, and

plain water. These solutions do not provide the salt, starch and protein necessary to

prevent dehydration in cases of large stool losses. But they would adequately replace

losses in most cases, especially if given as well as foods that contain some salt. Use of

such drinks should be considered when the use of food based fluids containing salt is not

feasible.

|

Prevention or treatment? To treat dehydration, once it has developed, it is essential to replace water

and salts lost during diarrhoea. Giving the standard WHO/UNICEF formula ORS is the best

way to do this, because it provides exactly the right balance of glucose and salts. Other

solutions containing the right amounts of sugar and salt, such as a carefully measured

sugar-salt solution, are also good. It is always better to give fluids of some sort than

not to give fluids at all. To prevent dehydration, the formula of solutions given is less important: the

main thing is to give extra fluids as soon as diarrhoea begins, and to continue feeding.

Home management is important because, if effective treatment for diarrhoea is given at

home, dehydration can be prevented in many cases. What about cereals? Oral rehydration solutions made from the same formula of salts as WHO/UNICEF glucose

ORS, but with rice powder instead of glucose, have proved effective in treating

dehydration. More research is, nevertheless, needed on some aspects of cereal based ORS

before it can be widely promoted. Home made cereal based fluids have also been found to be

at least as good as other home fluids for ORT.

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 41 June 1990

2 Page 3 4 2 Page 3 4

Recommendations

|

Always

continue breastfeeding a child with diarrhoea.

1. Home fluids to prevent dehydration (in order of effectiveness) include:

- oral rehydration salts (ORS) solution (although designed to treat dehydration, ORS may

be used, if available, as a home fluid from the start of diarrhoea to prevent dehydration)

- food based fluids (such as soups and porridges)

- sugar-salt solution

- other drinks (including plain water)

Food should always be given as well, with all of these fluids. |

2. Any home fluids used should be:

- readily available - easy to make from cheap, widely available ingredients

- safe - so that the recipe will not contain too much salt (or sugar) even if it is only

followed approximately

- familiar - the fluid or recipe should be well known

- acceptable for use during diarrhoea - with acceptable taste and no cultural barriers

- easily and readily given in large enough quantities

3. Home fluids should contain salt if possible. Otherwise, salt can be given in food.

Unsalted fluids should still be given if it is not possible or practical to give fluids

containing salt.

4. For food based fluids, it is usually best to use recipes which normally include a

safe amount of salt. Otherwise, salt can be added, if this is practical - 3g of salt per

litre of fluid is ideal (but up to 6g per litre would still be safe).

5. If sugar-salt solution is used, a recommended composition is 50

mmol/litre of salt

and of sugar (3g of salt and 18g of sugar per litre of water).

6. Home fluids should not be prepared by diluting weaning foods.

7. When food based fluids are used for home treatment, it is very important to make

sure that they are not regarded as food, because this could result in a sick child getting

too little to eat. These guidelines and recommendations were developed at an international meeting of

experts held by the World Health Organization in Baltimore, USA, in March 1990. How to make a rice based drink for oral rehydration

With careful teaching and practice, mothers in Pakistan have learnt to make this

safe and effective rice based drink for oral rehydration.

|

|

1 Take one handful (20 to 25 grams) of rice grain. Wash and soak the rice in water until

it is soft. |

|

|

2 Grind the soaked rice with pestle and mortar (or any other grinder) until it becomes a

paste. |

|

|

3 Put two and a quarter glasses of water (about 600ml) into a cooking pot and mix in the

rice paste. |

|

|

4 Stir well, and heat the mixture until it begins to bubble and boil. Then take the pan

off the fire, and leave the solution to cool. |

|

|

5 Add one three finger (up to the first finger joints) pinch of salt (1.5 grams) to the

mixture, and stir well. The solution is now ready to be given to the person with

diarrhoea. |

Storage: this solution should be covered and kept in a cool clean place. It should be

used not more than six to eight hours after preparation. After this time, throw away any

solution which is left over. Pictures and text taken from Elliott, K, et al. (eds), 1990. Cereal based oral

rehydration therapy for diarrhoea (symposium report), page 51. Aga Khan Foundation and

International Child Health

Foundation. See="#page5">page 5 for publication details. Further reading: Molla, A M, et al., 1989. Food based oral rehydration salt

solutions for acute childhood diarrhoea. Lancet ii: 429-31.

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 41 June 1990

3 Page 4 5 3 Page 4 5

Cereal based ORT DD presents short reports of four recent studies. Sorghum ORS: Rwanda

Sorghum flour is the main ingredient of traditional weaning foods in Rwanda. It was

tested as a base for ORS in the treatment of 100 children with acute diarrhoea. The

children included in the study were boys with good nutritional status, aged six to 24

months, who had had diarrhoea for less than three days with moderate dehydration (loss of

five to nine per cent of body weight). Children were not included if they had dysentery,

fever on admission (temperature over 39° C) and/or the presence of another severe

infection (such as pneumonia or measles). During the first six hours (the 'rehydration

phase') children were given 100ml/kg of either sorghum based ORS or WHO/UNICEF ORS.

Breastfeeding was continued during the rehydration phase and food (milk and bananas) was

re-introduced as soon as rehydration was achieved. On admission, there was no difference between the children given sorghum ORS and those

given glucose ORS. However, the sorghum based ORS group showed a significant reduction in

the duration of diarrhoea, in the total ORS intake and in the total output of stools. This

study was a hospital based clinical trial, and it remains to be seen whether an ORT fluid

based on sorghum can be used successfully in

the community. Lepage, P, et al., 1989. Food based oral rehydration salt solution for acute

childhood diarrhoea. Sweet potato water: Papua New Guinea

In Papua New Guinea, there are limited choices for the selection of suitable home

fluids because no cereal grains are grown locally. In the coastal and lowland areas

coconut water is widely available and health workers recommend it for preventing

dehydration. However, in the highlands no suitable fluids are available. This problem led

to a pilot study of the efficacy and safety of a solution made from kaukau (sweet potato)

- the staple crop in many parts of the country, widely grown in the highlands. After

trying various recipes, a fluid was produced by boiling two pieces of kaukau in 1.5 litres

of water for 35 minutes. The potato was then mashed and water added to make one litre of

drinkable solution. Three grams of salt were also added. The sweet potato solution was then compared with the standard WHO formula ORS in a

small study. Thirteen children with mild to moderate dehydration caused by acute diarrhoea

were treated with WHO/UNICEF ORS and ten were treated with kaukau-salt solution. The ages

in both groups ranged from four to 23 months and there were approximately the same number

of cases of mild and moderate dehydration in each group. The average time for rehydration

was the approximately the same for both groups. There were no side effects in the kaukau

group and all infants seemed to like the taste of the solution. Mothers and nursing staff were enthusiastic about its use. Although this pilot project involved very small numbers of patients, the results were

encouraging and suggest that sweet potato solution could be both safe and effective for

ORT, and culturally acceptable. Further studies are planned for 1990 to confirm the safety

of solutions prepared at home by mothers. Howard, P, et al., 1989. Proposed use of sweet potato water as a fluid for oral

rehydration therapy for diarrhoea. Papua New Guinea Institute of Medical Research,

Goroka,

Papua New Guinea. Wheat ORS in refugee camps

Mothers in Afghan refugee camps in Pakistan have been taught to use packet oral

rehydration salts, and to mix a home sugar-salt solution (SSS) for children with

diarrhoea. However, most mothers mix SSS incorrectly, leading to the risk of an

ineffective or harmful solution. Because research shows positive results with cereal based

ORS, it has been suggested that home made wheat and/or rice solutions would be better home

solutions. Research was undertaken to find out if mothers would use wheat based solutions - wheat

is cheap and widely available. Women (mostly non-literate) were taught the wheat solution

recipe: two fistfuls of wheat flour and a two to three finger pinch of salt per litre of

water. Teaching was carried out in homes and basic health centres by trained female health

workers. Follow up visits were carried out between two weeks and two months later to find

out: if mothers could still make the recipe correctly; if they had used it when their

children had diarrhoea; and what they thought of it. Of the 64 women interviewed, 60 per

cent said they gave one of the rehydration solutions on the first day of diarrhoea (other

fluids given on the first day included a yoghurt drink, green tea, traditional herbal

drinks and rice water). There were no cultural beliefs to prevent the use of a wheat based solution for

diarrhoea. Depending on the location and the method of teaching used, between 40 and 94

per cent of the women could demonstrate making the wheat based solution correctly. They

liked the wheat solution, as the taste is familiar and wheat flour is used every day to

make bread. Mothers also found the recipe easy to make. When discussing which solution the women preferred, and why, most mothers said all the

solutions were good. When asked which was easier, a significant number said that the

wheat, salt and water solution was a little easier than both rice water and

SSS, because

rice needed to be cleaned and washed and cooked longer, and SSS needed correct

measurement. While many thought rice water tasted best, they suggested that it was not

practical because of its expense (rice is considered to be a luxury and is not kept in

most Afghan homes). The Afghan women in this study learned the new recipe quickly and had

good recall when followed up. They knew why and when to give ORT, and continued to give

other foods in addition to the wheat solution, showing that they did not confuse the

wheat-salt solution and food. For Afghan families, sugar is expensive, ORS packets

unavailable, and it may not be possible to mix SSS correctly. Therefore, it is worthwhile

to continue to study wheat based, or both wheat and rice based solutions as alternatives

or additions to the sugar-salt solution being taught now. Siener, K, 1989. Wheat based ORS for Afghans, International Rescue Committee,

Peshawar, Pakistan. Bangladesh: field trials of rice based ORS Studies were carried out on rice based oral rehydration therapy from 1982 to 1987.

Packets of rice based ORS were given to one group of mothers; glucose ORS packets to

another; and no packets to a third group of mothers who had access to local treatment

facilities. All the mothers of children aged under four years in the first two groups were

taught to prepare and use ORS. Use of ORT was highest in the rice ORS group, and lowest in

the control group (where drugs were also most often used).

|

Cereal based oral rehydration solution may reduce the duration

of diarrhoea.

Duration of diarrhoeal illness was shortest in the group given rice ORS, in which more

than 60 per cent of children with non-dysenteric diarrhoea recovered within three days,

and less than one per cent suffered beyond 14 days.

|

Of the children given glucose ORS, 30 per cent recovered within three days, and about

three per cent still had diarrhoea after 14 days. In the third group, only six per cent

had recovered in three days, and 12 per cent had diarrhoea after 14 days. Bari, A, et al., 1989. Community study of rice based ORS in rural Bangladesh,

International Centre for Diarrhoeal Diseases Research, Bangladesh. More information about these and other studies is available from DD.

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 41 June 1990

4 Page 5 6 4 Page 5 6

Glossary Dehydration: the loss of water and salts caused by diarrhoea. Serious

dehydration can cause death.

Oral rehydration therapy (ORT): the administration of fluid by mouth to prevent

or correct dehydration.

Oral rehydration salts (ORS): the standard WHO/ UNICEF formula of glucose and

salts for ORT. Also known as 'glucose ORS'. Dissolving the salts in water makes ORS

solution.

Cereal based ORS: the standard WHO/UNICEF recommended formula but with 50 grams

of cereal instead of 20 grams of glucose (to be added to one litre of water). The cereal

contains starch which is broken down into glucose during digestion.

Cereal based ORT: the giving by mouth of a rehydrating fluid which is a thick

but drinkable mixture of a starchy food (approximately 50 to 80 grams per litre of water)

preferably with salt added (about three grams per litre of fluid).

Sugar salt solution (SSS): a solution containing only sugar, salt and water in

precise quantities (18 grams of sugar, three grams of salt and one litre of water).

|

International meeting

A symposium held in Karachi, Pakistan in November 1989 brought together many experts to

discuss the latest findings from studies of cereal based solutions for oral rehydration

therapy. Participants examined the scientific evidence supporting the claim that cereal

based ORS solutions can reduce stool volume and duration of diarrhoea. Clinical trials

reported showed that a range of cereals and starchy foods are as effective as glucose in

ORS for preventing and treating dehydration. Cereal ORS has been found to be especially

successful in cases of cholera. Further research was recommended in patients with

non-cholera diarrhoea, and in young children under four months of age or with

malnutrition. Cereal based ORS may prove a useful alternative to standard ORS, but more

research is needed to define its relative usefulness for young children with acute

diarrhoea. And it is important to find out if cereal ORS is better than standard ORS given

with cooked cereal food. Programme issues

The potential advantages and difficulties of introducing cereal based ORS into

diarrhoeal disease control programmes were also discussed. Where programmes have

established widespread distribution of ORS packets, or have a policy of promoting

sugar-salt solutions, it may not be advisable to introduce cereal ORS as an option,

because this may cause confusion or undermine existing health education. Where this is not

the case, and communities do not have access to standard ORS (in packets or otherwise)

cereal ORS could be an acceptable and effective option. Home use issues

Specific considerations discussed relating to promotion of cereal-salt solutions for

home use included:

- which cereals are most available and acceptable, as well as effective

- requirements for home preparation of cereal based solutions, including mothers' time and

fuel availability

- teaching and training required to ensure that cereal-salt solutions are safe and given

in timely and adequate amounts

- ensuring that the potential problem of confusion between cereal based ORT and food is

avoided.

Copies of the meeting proceedings are available. Details from Aga Khan Foundation, P

O Box 435, 1211 Geneva 6, Switzerland; and ICHF,

American City Building, Suite 325, 10277 Wincopin Circle, Columbia MD 21044, USA.

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 41 June 1990

5 Page 6 7 5 Page 6 7

How to feed a baby who cannot breastfeed

Cup feeding is much safer than bottle feeding and can be more practical than using

a spoon. Breastmilk is always the best food for babies, who need nothing else until they are

four to six months old. But, babies who are very small or ill may be too weak to suck at

the breast, and so must be fed - with breastmilk if possible - in another way. Why is cup feeding necessary?

Breastfeeding is the ideal way to feed a baby because breastmilk is the best possible

food and drink, and it gives the baby protection against diseases. With breastfeeding,

food for the baby is always ready and free from germs; and both mother and baby benefit

from close contact. However, another way of feeding is necessary when breastfeeding is not possible, and

feeding with a cup or spoon is the best and safest alternative. Breastfeeding may not be possible if:

- a baby is too weak to suck, for example during and after illness, or if it is born early

and very small

- the mother is very ill, or the baby has no mother or other woman to breastfeed it

- the mother cannot stay with her baby all day and a relative or friend has to feed the

baby.

Can you give breastmilk from a cup? Yes, definitely. If breastfeeding is not possible, the second best option is for the

mother to express breastmilk into a cup.

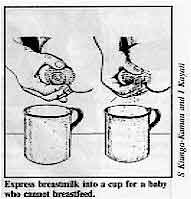

|

Express breastmilk into a cup for a baby who cannot breastfeed. The baby can then still have the benefits of breastmilk, even if it cannot breastfeed.

Other milks should be given only if no breastmilk is available from the mother, another

woman or a breastmilk bank.

|

|

When can you start cup feeding? Whenever it is necessary - even straight after birth. Any baby who can swallow can

drink from a cup. How do you feed a baby with a cup?

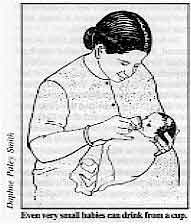

|

Even very small babies can drink from a cup Just hold the baby comfortably in your arms, and hold the cup to his or her lips. Be

careful not to tip the cup too far or too fast for the baby to swallow all of the milk

coming out of it. Give a little at a time, with short rests in between, especially if the

baby is sick or weak. Ordinary open cups should be used, not those with covers or spouts

which are too difficult to clean, and need to be sterilised like bottles.

|

What about bottle-feeding?

Bottle-feeding is dangerous because it is very difficult to keep bottles and teats

clean and free from germs without careful and regular sterilisation. Feeding bottles are a

major cause of infant diarrhoea. Because the bottles must be boiled before each feed,

bottle-feeding costs a lot in fuel, water and time. Bottle-feeding also stops babies

wanting to suck at the breast and makes them suck in a way which can cause sore nipples.

Bottle-feeding should always be avoided. What about spoon feeding? Spoon feeding is much safer than bottle feeding because spoons and bowls or cup are

much easier to clean. But it can take a very long time to give a baby enough food or fluid

using a spoon. Both the mother (or other caretaker) and baby are likely to get tired or

distracted before the baby has had enough food. However, if the baby can take only very

small amounts of milk, for example when there are breathing difficulties, or you think the

baby may choke or vomit, then it may be better to use a spoon than a cup. Acknowledgement: the information on this page is taken from the IBFAN

(International Baby Food Action Network) Statement on Cups. Copies available from

IBFAN-Africa, P O Box 34308, Nairobi, Kenya. More information

Feeding low birth weight babies IBFAN, 1986, VHS, 29 minutes. A training video

tape for health workers. This video demonstrates cup feeding of babies as small as 1.7kg.

Copies are available from: UNICEF, Communication and Information Services, P O Box 44145

Nairobi, Kenya; or contact the UNICEF office in your country. Breastfeeding - Dialogue on Diarrhoea Health

Basics series, originally published as an insert in DD issue 37, June 1989.

Six pages of information on breastfeeding including sources of further information and

publications. Copies available free of charge from AHRTAG.

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 41 June 1990

6 Page 7 8 6 Page 7 8

Cups are better than bottles because... CUPS have a simple shape and can be easily cleaned with soap and water.

Open CUPS do not encourage storage of feeds or carrying them about for several hours.

CUPS do not make babies unable or unwilling to suck at the breast.

CUPS used in hospital and by health workers teach the community a method which is safe

to use at home.

Using CUPS means that the small infant has some contact with the mother or another

person during feeds.

BOTTLES and teats have many awkward corners which cannot be cleaned except by boiling.

BOTTLES encourage the unsafe storage of feeds, increasing the chances for germs to

breed.

BOTTLES teach babies to suck in a way which makes them less willing to breastfeed.

BOTTLES used in hospital provide an example which cannot be safely or cheaply followed

by mothers at home.

BOTTLES can be propped up, depriving the baby of human contact. |

|

Diarrhoea and potassium |

|

Q What is the relationship between diarrhoea and potassium?

A

During diarrhoea, fluids and salts, including potassium chloride, are lost from the body.

If potassium (K+) lost is not replaced, low levels in the blood result (this is

hypokalaemia). However, most of the potassium in the body is stored in the cells, and so

measuring the level of potassium in the blood does not always give a true indication of

the status of body potassium. Children with protracted diarrhoea and malnutrition are

especially likely to be potassium-depleted. It may be wise to consider any child who is

undernourished and who has had diarrhoea for more than a few days likely to be

hypokalaemic, and to take appropriate action.

Q What are the signs of

hypokalaemia?

A

Hypokalaemia can lead to vomiting, anorexia or obstruction of the bowel. The signs of

severe K+ loss are weak and relaxed muscles, abdominal distension, and slowing of the

heart rate.

Q Does oral rehydration therapy replace lost potassium?

A

Children with diarrhoea need potassium during rehydration to prevent or replace any K +

loss. Packets of ORS formula contain enough potassium chloride (1.5 grams per packet for a

litre of water) to replace losses during diarrhoea. Proper use of ORS usually ensures that

any hypokalaemia is corrected within 24 to 36 hours of starting oral rehydration therapy.

Where packets of WHO/UNICEF ORS are unavailable, home made sugar-salt solutions

(SSS) and

home available fluids are usually used to prevent and (if necessary) treat dehydration.

SSS does not contain potassium, and other home available solutions also may not. It is

therefore important to give children adequate amounts of locally available

potassium-containing foods to replace losses, and to help restore appetite and food

intake.

Q What are good sources of potassium?

A

Fruits and vegetables are good sources. Those with the most potassium (in mmol per 100g)

include spinach (12.6) avocado (10.3), banana (9.0), pumpkin (8.0) and coconut water

(8.0). Plantain, papaya, oranges, grapefruit, tomato juice, carrot, pineapple, soya and

peanuts are also good sources. Thirty grams of banana supplies approximately 115mg of K +

; the same amount of K+ would also be supplied by 6g of defatted soy flour, or 20g of

lentils, peanuts or potatoes, and 30g of whole wheat flour or dark green leafy vegetables

(DGLV). Soy flour should be toasted, and DGLV should be steamed (since K+ is soluble in

water). In general, leaves may contain more potassium than fruits, although it will depend on

the type of soil in which the plant is grown. Where soil is very deficient in K + , plants

do not grow well, but probably maintain a minimal concentration of potassium. For small children who cannot eat large quantities of starchy foods like bananas,

drinking water which has been dripped through about 5g of wood ash may be a more effective

way of increasing potassium intake. The ash should be fresh (but cooled) and therefore

free of germs. The ash from some fresh water weeds, such as the water hyacinth, is an even

richer source of K+.

Q When should potassium rich foods be given?

A

Foods rich in K + should be given during diarrhoea and for at least a week afterwards to

ensure that potassium levels are returned to normal. References Dialogue on Diarrhoea issues 3 (Potassium losses and replacement in

diarrhoea) and 5 (Pirie, N W).

Moy, R J D, and Booth, I W, 1988. Acute diarrhoea: who needs potassium? (Editorial). J.

Trop. Paed. 34: 2-3.

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue no. 41 June 1990

7 Page 8 7 Page 8

Traditional recipe Thank you for DD39 on traditional beliefs and

treatments for diarrhoea. The Burundian traditional method is to give the patient some

honey and salt in a glass of water. I know this from experience - when I was a small

child, my mother gave me this mixture, and it always seemed to help. Simeon Bandy A Yera, P 0 Box 97, Gitega, Burundi.

Does ORS treat diarrhoea? Diarrhoea is recognised as one of the main killer diseases in children in developing

countries. Though the diarrhoea itself (more than three loose stools per day) is usually a

self-limiting problem, the death of many children can be caused by both the short and long

term effects of diarrhoea, including dehydration and malnutrition. Many efforts in Third

World countries are therefore directed at the fight against these results of diarrhoea,

not against the diarrhoea itself. In this, ORS plays an important role. In our approach to the parents of sick children we should be very explicit. What

parents worry about most is the diarrhoea, not dehydration or malnutrition. Though in our

approach we say that we treat the diarrhoea, in fact it doesn't always stop it. Some of

the methods used by parents to stop the diarrhoea can seem much more efficacious than

ours. For example, if they restrict feeding or buy 'anti-diarrhoeal' drugs in the market,

they see that the frequency of stools seems to diminish, but when they give oral

rehydration fluids and continue feeding, the number of loose stools does not always

diminish. This does not help to build trust in 'a new way to treat diarrhoea'. This problem has been raised in discussions with health workers in Cambodia who

remarked: 'We tried it, but the diarrhoea did not stop! ' We have realised that the

parents do not care so much, or understand, about dehydration. Dr Chhour Y Meng and Dr G van Bruggen, Phnom Penh National Paediatric Hospital,

Cambodia.

Dr N Pierce of WHO replies: Drs Meng and van Bruggen are correct that ORS does not stop diarrhoea immediately, but

neither do 'anti-diarrhoeal' drugs (they only restrict bowel movements). It is better to

tell parents that ORS is medicine to make their child feel better, and stronger. ORS will

make the diarrhoea stop, but after a few days.

Local beliefs Following the 'Viewpoints' on local beliefs about diarrhoea (DD

39) I would like to add some information from Kerala. Fewer

children here are dying of dehydration, because there is good access to medical services.

But, many people do not know how diarrhoea is caused, often believing that teething is

responsible. Mothers often give very diluted feeds of cows milk or infant formula to sick children,

fearing that less watery food will cause indigestion. This means that many children are

underfed and sometimes malnourished. Fewer mothers from richer families are breastfeeding

their babies. Most people do not understand that diarrhoea is caused by germs in food or

water, and that breastfeeding provides the best and cleanest possible food. Often, mothers

go from one doctor to another looking for an instant cure for their child's diarrhoea, not

realising that they are putting the child in danger by not giving it enough food. People do not understand that fluids are needed during diarrhoea - they believe that

giving a child more to drink will only increase the diarrhoea. Many mothers here know

about ORS, but instead of using it at home, they will want to see a doctor whatever their

financial or educational status. In Kerala, a two child family is accepted by most

parents, and they want to do everything possible to make sure that the children are

healthy. In our practice, we have found that home fluids such as home made rehydration

solutions, coconut water, and arrowroot gruel are more acceptable to children than

commercial ORS . Dr K Jacob Roy, Tropical Health Foundation of India, Guravayar Road, Kunnamkulam

680503, Kerala, India.

ORS for diabetics? I have a problem for which an explanation from your organisation will be of great help

to me and my colleagues. The problem is about management of moderate and severe

dehydration using ORS in diabetics (insulin dependent and non-insulin dependent alike),

since sugar forms a major part of the formula. Joshua N Wilson, Nguru Clinics and Maternity, P O Box 104,

Nguru, Borno State,

Nigeria.

Dr Peter Milla, Senior Lecturer, Institute of Child Health, London, replies: The problem is probably best considered in two parts: insulin dependent diabetes and

non-insulin dependent diabetes. As far as insulin dependent diabetes is concerned, the difficulty is no greater than

that posed for any severe infection in a diabetic dependent upon insulin, when control of

the diabetes may be disturbed. The carbohydrate load imposed by oral rehydration solution

is not likely to be greater than that contained in the diabetic's normal diet. Clearly,

however, the electrolyte disturbance may make control of the diabetes more difficult and

it should be managed in the same way as any other severe infective process. I think that

if one remembers that the carbohydrate intake of a patient with diabetes is likely to be

within the region of 100 to 200g of carbohydrate depending on the severity of the process

and the presence or absence of peripheral insulin resistance, then this allows between

four and ten litres of oral rehydration solution to be used each day if the patient is

taking no diet by mouth. With regard to non-insulin dependent diabetics, then the limiting factors are the

disturbance caused by the diarrhoeal infection and the carbohydrate restrictions imposed

by dietary management. For those on a 100g carbohydrate diet, then this is the equivalent

in carbohydrate terms to four litres of OR solution per day. I think in ordinary clinical

practice it is unlikely that this will pose a major problem.

|

Scientific editors Dr Katherine Elliott and Dr William Cutting

Managing editor Kathy Attawell

Assistant editor Nina Behrman Editorial advisory group

Professor J Assi Adou (Ivory Coast)

Professor A G Billoo (Pakistan)

Professor David Candy (UK)

Professor Richard Feachem (UK)

Dr Shanti Ghosh (India)

Dr Michael Gracey (Australia)

Dr Norbert Hirschhorn (USA)

Dr Claudio Lanata (Peru)

Professor Leonardo Mata (Costa Rica)

Dr Jon Rohde (USA)

Dr Mike Rowland (UK)

Ms E O Sullesta (Philippines)

Professor Andrew Tomkins (UK)

Dr Paul Vesin (France) With support from AID (USA), ODA (UK), UNICEF, WHO Publishing partners

BRAC (Bangladesh)

CMAI (India)

CMU (China)

Grupo CID (USA)

HLMC (Nepal)

lmajics (Pakistan)

ORANA (Senegal)

RUHSA (India)

Consultants at University Eduardo Mondlane (Mozambique)

|

Issue no. 41 June 1990

Page Navigation

This edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online is produced by Rehydration Project. Dialogue on Diarrhoea was published four times a year in English, Chinese, French, Portuguese, Spanish, Tamil,

English/Urdu and Vietnamese and reached more than a quarter of a million readers worldwide. The English edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea was produced and distributed by Healthlink Worldwide. Healthlink Worldwide is committed to strengthening primary health care and

community-based rehabilitation in the South by maximising the use and impact

of information, providing training and resources, and actively supporting

the capacity building of partner organisations. - ISSN 0950-0235 Reproducing articles

Healthlink Worldwide encourages the reproduction of

articles in this newsletter for non-profit making and educational uses. Please

clearly credit Healthlink Worldwide as the source and, if possible, send us a copy of any uses made of the material.

|

updated: 24 April, 2014

updated: 24 April, 2014

|