|

| |

Issue no. 18 - August 1984

pdf

version of this Issue version of this Issue

|

There is much information in this issue that is valuable

and useful. Online readers are reminded, however, that treatment guidelines and health

care practices change over time. If you are in doubt, please refer to

WHO's up-to-date Dehydration Treatment

Plans.

|

updated: 23 April, 2014

Pages 1-8 Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 18 -

August 1984

|

DDOnline

Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 18 August

1984  Page 1 2

Page 1 2

Making progress

Diarrhoea remains a major cause of ill health and death in developing countries -

especially among children. Much of this suffering is preventable and substantial progress

has been made since the World Health Organization set up its Control of Diarrhoeal

Diseases Programme in 1978 (see pages four and five). ORT: greater commitment required

The life-saving value of ORT is increasingly accepted around the world. However,

packets of oral rehydration salts (ORS) and simple instructions for their use are still

not reaching many communities where diarrhoea is worst. Also, some medical leaders are not

yet committed to ORT (see page="#page8">eight, letter from Trinidad). Support

from all health care professionals is crucial if ORT is to have the impact it deserves on

child mortality. Water and sanitation

|

Encouraging handwashing early

Oral rehydration prevents death from dehydration due to diarrhoea. It cannot stop the

transmission of diarrhoeal infections. Protective vaccines are being developed but will

take time to perfect. There are also constraints to overcome in their delivery (see Diarrhoea

Dialogue issues 14 and 16). Improvements

in water supplies and sanitation come slowly and can be costly. Progress in a UNICEF-

supported water programme in Nigeria is described on page="#page3">three and

shows how community involvement from the start is essential for success. News from the

Solomon Islands (see page="#page2">two) confirms this conclusion. Latrine

developments in Zimbabwe emphasize the value of a realistic approach to sanitation systems

(see page="#page7">seven).

|

Other interventions

Other important ways exist to diminish the spread and the harmful effects of diarrhoea

- immunization against measles, promotion of breastfeeding and the encouragement of

handwashing and personal hygiene (see Diarrhoea Dialogue issues="dd16.htm">16

and 17 and page="#page2">two in this issue). All

require well designed educational programmes which are appropriate to local circumstances

and resources. The="#page6">practical advice page in this issue tells how

people can make their own soap from simple ingredients. Importance of evaluation

Evaluation of all interventions is essential. The="dd20.htm">first issue of Diarrhoea

Dialogue in 1985 will concentrate on 'operational research. ' Simple observations

and experiments can be undertaken by health workers and their communities (see page="#page2">two) to find out when, where, why and how much progress is being made -

and how progress may be speeded up! KME and WAMC

|

In this issue . . .

- A review of the WHO Diarrhoeal Disease Control Programme

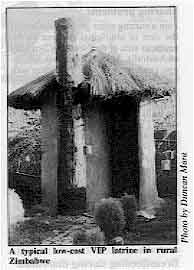

- Duncan Mara looks at low-cost latrines - the latest developments

- Practical advice - how to make soap

|

|

DDOnline

Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 18 August

1984  1 Page 2 3 1 Page 2 3

Solomon Islands' success The Solomon Islands look set to mark the end of the International Drinking Water Supply

and Sanitation Decade in 1990, by becoming one of the first developing countries to

provide access to safe drinking water for its entire population, estimated at 250,000. Two

main factors have contributed to this imminent success. Firstly, community participation

(communities have been involved in all stages of the development process and have also

been trained to maintain and repair their own water systems). Secondly, technologies that

are both appropriate and affordable, such as bamboo-reinforced water tanks, have been used

and the water supply systems have been introduced on a small scale, to match local needs. Health and Development, April 1984.

Water and sanitation: health impact?

A meeting was held at Cox's Bazaar, Bangladesh, in November 1983 to discuss the best

way of assessing the achievements of water and sanitation programmes. Such programmes are

implemented in the widely held belief that automatic improvements in health will result,

but this is not always the case. High expectations often come from the policymakers,

donors or governments investing in the programme, who want to see concrete results. On a

large scale, such programmes are extremely expensive. Another important factor is the

time-lapse which occurs before any improvements can be seen. Benefits such as reduction in

disease and improvements in nutritional status often only appear gradually. With these

factors in mind the Teknaf discussions centred on the following subjects:

- why/when/how often should health impact studies be undertaken?

- should the impact of water and sanitation on health be assessed independently of other

measurements of primary health care?

- can the project design and results be improved by taking preliminary surveys, and can

the results be applicable in other areas?

- what indices should be used to measure improvements, for example, the incidence of

diarrhoea, worms, eye and skin diseases or nutritional status, all of which may be

influenced by other factors?

- within what timescale should the study be carried out?

- what are the best ways of interpreting the findings and of communicating and

implementing the recommendations and conclusions drawn from these findings?

Findings

- It was suggested that using nutritional status as an indicator of improvements in health

would be more useful than using the incidence of diarrhoea. Participants gave evidence to

show that improved water supply does not necessarily reduce the incidence of diarrhoea.

Instead, it affects the type of pathogens causing the diarrhoea, and hence the type of

diarrhoea. Diarrhoeal incidence and duration are very hard to measure accurately,

depending largely on memory, whereas nutritional status is easier to measure and also

reflects diarrhoeal incidence and duration.

- Less direct but important health benefits may result from water improvements, if mothers

no longer have to spend several hours each day fetching water. Nutrition could improve if

mothers had more time and energy for growing crops, cooking, and looking after their

children, including breastfeeding.

- The participants concluded that the best time to evaluate a programme is from one to

three years after the project has started. This gives enough time for the work to have an

impact, but is soon enough to minimize the effects of other factors which can influence

the results.

- Another important finding discussed was that improvements in health seem to be directly

related to the amount of water used - for example, in St Lucia, this was the single

most important factor, and the amount of water used was inversely related to the numbers

of childhood illnesses.

Based on material presented in 'Glimpse' Vol 6 No. 2 March/April 1984.

Handwashing helps

Diarrhoea is usually caused by faecal-oral transmission of germs. It is difficult to

avoid this in dirty and contaminated situations. Simple personal hygiene, especially

hand-washing after using the toilet and before preparing or eating food, can reduce the

rate of diarrhoea attacks. This has been shown independently in several studies from as

far apart as Guatemala, Bangladesh and the USA where attack rates were reduced by between

14 and 48 per cent (Feachem 1984). At least two steps are required to achieve such an improvement: education about the

hygiene measures required to reduce transmission, and a change in the pattern of

behaviour. Economic constraints and cultural barriers prevent this in many communities.

There is also a need to identify the most important protective actions and the most

appropriate messages in any group. However, these limitations should not stop everyone

practising and preaching the value of handwashing in preventing diarrhoea. Feachem R G, 1984 Bull. WHO 62.1. WHO water checklist A recent WHO publication, Rural water supply: operation and maintenance - eight

questions to ask, is intended to be a guide for planners and engineers involved in

rural water supply projects. The eight questions consider such factors as site conditions;

socio-economic conditions; project planning and development; the influence of resource

availability outside the community; system management; manpower development and training

and on-site resource availability. The publication (reference ETS/83.9) is available in

English and French (shortly to be available in Spanish) from WHO, 1211 Geneva 27,

Switzerland. In the next issue . . . .

We will concentrate on oral rehydration therapy (ORT). Although ORT has already saved

thousands of lives, it is still not reaching all those who need it - DD19

looks at how ORT is being promoted and at research into an improved ORS formula.

|

|

DDOnline

Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 18 August

1984  2 Page 3 4 2 Page 3 4

| Water programme in Nigeria |

Promoting health

A successful UNICEF-assisted project in Imo State began health and hygiene

education long before water supplies were actually installed. The UN Water Decade aims to provide 'Clean Water for All by the Year 1990'. Through

this it hopes to reduce illness caused by inadequate water and sanitation facilities.

Evaluations have shown that better health does not automatically result from improvements

in water supplies and sanitation. One project which may provide data about the impact of

such changes on health is a UNICEF-assisted programme in Imo State, Nigeria, begun in late

1981. The most important aspect of this particular programme is the emphasis on health and

hygiene education, to try to change water use and excreta disposal practices so that the

people gain the maximum health benefit from the project. Many previous projects have not

led to improvements in health because the educational component has been introduced as an

'afterthought' once the new facilities have been established. Sequence of events In each local government area, such as Ohaozara in North-eastern Imo State, the

programme is initiated in overlapping stages. First, the community mobilisation team meets

with government officials, community leaders and villagers to explore village needs,

explain the project and its aims and foster a spirit of local ownership in the project.

Next, each village chooses four village-based workers (VBWs) who undergo a four week

training programme under the direction of the training team. Meanwhile the sanitation team

has the task of assisting villagers in building ventilated improved pit latrines. All this

happens before drilling of boreholes for water is even begun - the community is persuaded

to alter existing habits and becomes aware of preventative health measures before the

arrival of new water supply. In five villages in Chaozara local government area, the

activities of an evaluation team have preceded all other activities by one year. The team

collects data at regular intervals to allow evaluation of the project's impact on the

health of young children. An important aim of this evaluation is to collect information on

diarrhoea incidence and aetiology. A simpler evaluative procedure to monitor the

functioning and use of facilities rather than health impact has been developed and is

being introduced into a sample of project villages. An important characteristic of the

five project teams - mobilization, evaluation, training, sanitation and drilling and pump

installation - is that they are seconded from six state government ministries and include

a variety of personnel ranging from sanitarians and health educators to social

statisticians. Overall coordination of the teams and the pace at which they work is

carefully handled so that the balance of village life is not unduly disturbed. Hygiene education and community involvement At village level the VBWs have responsibility for the hygiene education component of

the project - for example, promoting proper water use habits and excreta disposal

practices. The VBWs, usually two men and two women, are selected by their fellow villagers

and must fulfill certain criteria. They must be established members of the community,

married (preferably with children) and able to read and write to a minimum standard. A

steering committee is formed in each village, consisting of respected members of the

community. This committee supports VBWs and organizes VBW payment. Convincing fellow

villagers to change their hygiene habits is not always easy. Strong support from the

steering committee is necessary to give the VBWs authority in the eyes of the villagers.

Enthusiastic community involvement is also necessary to raise funds and organize the

building of latrines. Programme results

|

Arrival

of new water supply

Photo by Deborah Blum The success of the programme depends to a great extent on the continued commitment of

the state and local governments, individual communities and on the educational activities

of the VBWs. Although it will be some time before the results of the health impact

evaluation are known, important accomplishments are already evident. The Imo State project

is now serving 370,000 people or some 8-9 per cent of rural Imo State at a low per capita

cost. The Imo State government is committed to extend the project throughout the state and

the federal government has agreed to introduce the project model in at least five other

states.

|

The project is already underway in two of these states with encouraging results. In

Gongola state in particular, community mobilisation has led to striking transformations in

project villages and fostered a spirit of community self-improvement. For example,

environmental sanitation campaigns and tree and flower planting activities have

accompanied the project activities. Finally, in participatory states and local government areas the project has established

an infrastructure to undertake other primary health activities. It is no surprise that

project areas have been particularly chosen as starting points for the national Expanded

Programme on Immunization (EPI), nor that the Imo Project has been recommended by the

Nigerian Council on Health as an example of primary health care to be visited by

delegations from all other states. Deborah Blum, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Keppel Street, London

WC1E 7HT. Information also taken from Issue 116, UNICEF News.

|

|

DDOnline

Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 18 August

1984  3 Page 4 5 3 Page 4 5

| Five years on: review of the WHO/CDD programme |

Strengthening national initiatives

Reducing childhood illness and death due to diarrhoea is a major priority for WHO.

We report on its achievements in this area since 1978. The WHO Programme for the Control of Diarrhoeal Diseases (CDD) was set up with the

formidable task of assisting WHO member countries to reduce the high levels of illness and

death - especially in children under five - due to diarrhoeal diseases. The CDD Programme

has a health services component and a research component. Information about Programme

activities is circulated through a mailing list of 5,000 and through publications such as Diarrhoea

Dialogue. CDD works closely with a number of other agencies, including UNICEF and the

League of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, in the promotion of oral rehydration

therapy (ORT) around the world. UNICEF and WHO recently published a

joint statement on the

management of diarrhoea and use of ORT(1). Health services component

By the end of 1983, seventy two countries had received assistance from CDD in planning

national diarrhoeal disease control programmes. Of these, 52 countries are now

implementing plans. Emphasis is put on sound programme planning; the training of health

workers at all levels; local production and development of oral rehydration salts (ORS);

and evaluation of programme activities. The major strategy of all the national diarrhoeal

disease control programmes is proper case management of acute diarrhoea with oral

rehydration therapy, emphasizing both the treatment of dehydration by use of ORS

throughout the health system and prevention of dehydration through treatment and

use of appropriate home-made solutions. Training:

The training of national CDD programme managers and others involved in diarrhoeal

disease control work continues to be a priority. In 1983, five training courses for

programme managers took place, attended by 170 people from 50 countries. Since this

particular course began, 677 people from 117 countries have been trained. In 1983, a new

course was launched in nine countries, aimed at first line supervisors in the health

system. The course deals not only with diarrhoeal disease control but also looks at other

primary health care interventions. So far, 410 people have attended the courses, coming

from 14 countries, and, in Thailand and Indonesia, the course material has been translated

for national use. The same material is being used by UNICEF training workshops; also in combined courses

between CDD and the WHO Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) to strengthen curricula

of nursing schools, the first being held in Egypt. Recognizing the importance of training

peripheral health workers in the use of ORT, CDD recommends that such training courses

should use nationally prepared materials based on the treatment and training sections of

the supervisory skills course. Technical training activities also continue in clinical

management; laboratory diagnosis; epidemiology and environmental health. Priority is given

to the clinical management courses for physicians and other senior level workers. As part

of the effort 37 regional and national CDD training units have been established. ORS production:

An essential part of national programmes is the availability of sufficient ORS packets.

CDD continues to work closely with UNICEF on the production and distribution of packets.

Thirty-eight developing countries are now producing their own ORS.

|

ORS production in Indonesia

Photo by H. Faust, WHO In 1983, UNICEF distributed 29 million packets to 78 countries, and other bilateral

agencies also provided packets through their own aid programmes. Commercial, national and

multinational companies have been encouraged to increase their production of ORS.

Important studies have been carried out during 1983 on the substitution of sodium

citrate for sodium bicarbonate in the ORS formula. Laboratory and clinical studies

have shown that not only is the new formula more stable in tropical conditions but also

results in some 20 per cent less stool output. This is because there is increased

intestinal absorption of sodium with citrate as compared with bicarbonate. The citrate

formula is also cheaper to pack. (Issue 19 of Diarrhoea Dialogue

to be published in November 1984 will carry a full report on the citrate formula).

|

|

Evaluation:

Increasing emphasis has been put on developing CDD programme capability to evaluate

access to and use of ORS in children under five; impact of ORT in hospitals; and morbidity

and mortality due to diarrhoea. Information on all these subjects is essential to improve

the planning and development of national diarrhoeal disease control programmes. Guidelines

have also been developed to assess the cost-effectiveness of ORT at country level and

these are being tested in Indonesia and Honduras. An evaluation procedure has been

developed with the Environmental Health Division of WHO to assess the operation and use of

water supply and sanitation facilities.

|

|

DDOnline

Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 18 August

1984  4 Page 5 6 4 Page 5 6

| Five years on: review of the WHO/CDD programme |

Research component Biomedical:

The biomedical research component of the CDD Programme has made important advances

during the past year on many fronts - from studies into more effective ORS to clinical

trials for typhoid and rotavirus vaccines. CDD is now supporting 147 biomedical research

projects - 46 per cent of which are in developing countries. Research areas include

diagnostic microbiology, including simplified tests which can be used at the periphery

(see Diarrhoea Dialogue issue 9); immunology and vaccine

development, particularly in relation to typhoid fever and rotavirus infections (see Diarrhoea

Dialogue issue 16); drug development and the management of

acute diarrhoea. In the latter category, as well as the research into the citrate ORS formula described

above, CDD has actively pursued the development of even more effective ORS formulations -

both home-based and in packets. Studies have shown that a rice-based solution can reduce

diarrhoea output by up to 50 per cent. Trials are now being carried out to see whether

similar food-based solutions can be made from dal or maize. Unfortunately, the first

indications are that at least some of these solutions seem to ferment rapidly, which may

restrict their usefulness. Alternative methods of enriching ORT solutions are being

explored. Work has continued in the evaluation of traditional drugs for diarrhoea in

countries such as Bangladesh, China and Madagascar. Studies are also underway to examine

the absorption of different foods during and after diarrhoea. Information on these

approaches should be available at the end of 1984. In the area of epidemiology and ecology, research has shown that Vibrio cholerae can

survive in the environment in different forms. This important observation may explain the

seasonal occurrence of cholera in endemic areas. Operational research:

|

Convincing doctors: management of diarrhoea using ORT in Bangladesh

Eighty-four operational research projects have now been supported by the CDD Programme,

the majority of them looking into aetiology/epidemiology or case management of acute

diarrhoea, especially the delivery of ORT in local settings . Overall, research activities

have been strengthened by CDD assistance to various institutions in developing countries

for training purposes. One important development has been the collaboration with Mahidol

University and the Ministry of Health in Thailand in the preparation of a proposal for

setting up a Centre for the Trial of Vaccines against Infectious Diseases at Mahidol

University. Research priorities in the area of chronic diarrhoea have now been established

and it is hoped to begin supporting research in this key area next year. Other new

research projects will include activities related to the additional diarrhoeal disease

control interventions of breastfeeding; use of clean water and sanitation; handwashing;

and measles immunization.

|

More information on all the Programme activities described above is available from

the Director, Programme for the Control of Diarrhoeal Diseases, WHO, 1211 Geneva 27,

Switzerland. (1) The Management of Diarrhoea and Use of Oral Rehydration Therapy. Joint

WHO/UNICEF Statement, 1983 (available in five languages from WHO).

|

|

DDOnline

Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 18 August

1984  5 Page 6 7 5 Page 6 7

How to make soap

This article shows how soap can be made cheaply and easily on a small scale, in

the home or village, using locally available ingredients.

Soap is a very great help to people in being able to keep themselves and their

surroundings clean, and is therefore important in preventing the spread of disease. In

some countries soap is unavailable or very expensive. The table below shows the

ingredients necessary to make soap.

Basic ingredients

For one bar of soap you will

need:

- 230 ml (1 cup) of oil or clean, hard fat.

- 115 ml (½ cup) of water.

- 23.5 gms (5 teaspoons) of caustic soda (sodium hydroxide) crystals or lye.

- Borax and a few drops of perfume are optional.

For 4 kg of soap you will need:

- 3 litres/2.75 kg (13 cups) of oil or clean, hard fat.

- 1.2 litres (5 cups) of water.

- 370 gms of caustic soda (sodium hydroxide) crystals or lye.

|

- Animal fats such as tallow, mutton fat, lard, chicken fat or vegetable oils such as

olive, coconut, palm and palm kernel, cottonseed, castor, maize, soybean, safflowers and

groundnut can be used. The best soap is made from a mixture of oil and fat. Even polluted

fat can be used as long as it is first melted then strained through a finely woven cloth.

Coconut oil makes a softer soap than the other oils (because it is low in stearic acid)

and can be greasy. It is however the only soap that will produce a lather in seawater - so

in some cases using some coconut oil is good.

- The best water to use for soapmaking is soft water. Rainwater is therefore good. Hard

water contains mineral salts which hinder the cleansing action and lathering of the soap.

To soften water, add 15 ml or 1 tablespoon of lye to 3.8 litres/ 1 gallon of hard water

and leave to stand for several days after stirring. The water poured off from the top,

leaving a sediment behind, is soft water.

- Only caustic soda can make hard soap. The alternative, if caustic soda is not available,

is potash or lye, leached from ashes. Caustic soda should be stored in sealed containers

to prevent absorption of moisture from the atmosphere.

- Borax, although not necessary, can be used to improve the appearance of the soap and

increase the amount of suds produced.

- Perfumes can act as a preservative, but, if used should be resistant to alkali. For 4 kg

of soap one of the following should be used: 4 teaspoons of oil of sassafras; 2 teaspoons

of oil of wintergreen, citronella or lavender; or 1 teaspoon of oil of cloves or lemon.

- Different proportions of ingredients produce different types of soap: for hard scrubbing

soap use tallow for the fat quota; for laundry soap use ½ lard/cooking fat with ½

tallow; for toilet soap use ½ tallow with ½ vegetable oil.

Equipment

To make soap you will need:

- Two large bowls or buckets made from iron, clay, enamel or plastic. Never use aluminium

- it is destroyed by lye/caustic soda.

- Measuring cups made from any of the same materials as above, again except for

aluminium.

- Wooden or enamel spoons, or smooth sticks for stirring.

- Watertight wooden, plastic, cardboard or waxed containers for a mould; gourds, coconut

shells or split bamboo halves can also be used.

- Cloth or waxed paper can be used to line the moulds so that the soap can be easily

removed.

|

Method

- Dissolve caustic soda in water to produce lye water.

- Pour oil into separate container (add borax at this point if desired).

- Pour the lye water slowly onto the oil, stirring continuously in one direction. If an

oil-fat combination is being used add the melted and cooled fat to the oil/lye solution.

- Add perfume/ colouring now if desired/ available.

- When the mixture has a thick consistency, put into lined moulds/cooling frames and leave

to set for two days.

- If fat only is being used, it should first be clarified by boiling it up with water and

allowing the mixture to cool down and set. The clean fat can then be easily separated and

melted again for soapmaking. Always allow the fat to cool down before adding to the lye

water, slowly stirring in one direction.

Once the soap is made

- Do not move the moulds.

- When ready, cut the bars into slabs/ smaller bars.

- Stack on trays and leave to dry thoroughly for 4-6 weeks.

- When dry, cover to prevent further loss of moisture.

- If the soap is not set after two days, or there is grease visible on top of the soap,

leave it to set a little longer.

How to recognise good soap

Good soap should be hard, white, clean-smelling, tasteless and should shave from the

bar in a curl. It should not be greasy or taste unpleasant. The main point to remember is

that the soap you make does not have to be perfect. As long as it is usable it is better

than no soap. If, however, problems occur, there may be several reasons. Spoiled soap only

happens when:

- the wrong materials are used.

- the oil or fat is too rancid or salty.

- the lye water used is too hot or cold.

- the mixture is stirred either too fast or not long enough.

To reclaim soap:

- cut into small pieces and add to five pints of water.

- melt over a low heat.

- boil the mixture until it becomes syrupy.

- pour into a mould and leave for two days before cutting up as before.

| WARNING caustic soda is very dangerous and can burn skin and eyes.

Protective gloves should be worn if possible when making soap. If burns occur they should

be washed immediately with cold water and then treated with vinegar or citrus juice. Never

add water to caustic soda-always add the soda to the water. |

For further reading, please write to AHRTAG

|

|

DDOnline

Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 18 August

1984  6 Page 7 8 6 Page 7 8

On-site sanitation

Duncan Mara describes some recent developments in the

design of VIP latrines and pour-flush toilets On-site sanitation systems can provide major health benefits at a fraction of the cost

of sewerage. They do not depend on piped sewerage or regular emptying methods of

sanitation that will never reach the vast majority of people in developing countries. The

Technology Advisory Group (TAG) of the World Bank/UNDP has published information on the

designs of ventilated improved pit (VIP) latrines and pour-flush (PF) toilets, which have

been developed in Botswana, Brazil, India, Tanzania and Zimbabwe. Two general design

manuals will shortly be published. Issue 5 of Diarrhoea Dialogue

described twin-pit VIP latrines and PF toilets. This review highlights some of the

developments that have taken place since then. VIP latrines

|

A

typical low-cost VIP latrine in rural Zimbabwe The most significant developments in VIP latrine design have come from Zimbabwe.

Latrines for rural areas can cost as little as US $10, since local materials - freely

available in the bush - are used extensively. The rectangular pit (1.5m x 0.6m x 3m) of

the low cost rural VIP latrine has a rough timber cover-slab, over which a spiral,

doorless superstructure is built in mud and wattle. The roof is thatched and the vent pipe

is made from a mat of reeds rolled up and plastered with cement mortar. A PVC-coated

fibreglass fly-screen is fixed at the top of the vent pipe. The only materials the

householder has to buy are the flyscreen, a bag of cement (to render the outside of the

superstructure and the vent pipe) some nails and tie-wire. This latrine can last a family

of six for over twenty years, although it needs regular annual maintenance to repair any

damage occurring during the rainy season. This is not a great problem, however, since the

latrine is built in almost the same way as the houses, so the local people already have

the necessary maintenance skills.

|

|

A slightly better, but more expensive design is available at US $46. The pit is

circular (1.2m in diameter) 3m deep and is covered by a reinforced concrete slab 1.5m in

diameter. The spiral super-structure and vent pipe are built with local burnt bricks,

which are readily and cheaply available in rural Zimbabwe. A thatched roof is often used

although ferro-cement ones are also common. Stainless steel flyscreens are now preferred

to fibreglass ones since they last longer. These brick VIP latrine designs are becoming

very popular in Zimbabwe, especially as timber for the low-cost version described above is

now in scarce supply. There is also more space in the brick latrines; this permits

'bucket' showers to be taken in greater comfort. Two beneficial effects of this are

improved personal hygiene and a lower rate of solids accumulation in the pit (the addition

of small volumes of water improves the bacterial breakdown of faecal material). In urban areas, single-pit VIP latrines can be used for population densities of up to

300 persons per hectare. At slightly higher densities it is possible to built alternating

twin-pit VIP latrines (of the type described in Diarrhoea Dialogue, issue 5) but, in major urban VIP latrine programmes, it is generally

better to use single-pit latrines which can be desludged at regular intervals (once every

2-5 years). In parts of Ghana and Brazil, in-house VIP latrines have been constructed -

the pit itself is partly outside the house, so that it can be desludged regularly. Pour-flush toilets The alternating twin-pit PF latrine design described in Diarrhoea Dialogue, issue 5, is still preferred wherever desludging is done by

hand, as in India for example. A single-pit design is more suitable if a vacuum tanker is

used to empty the pit, as in Brazil. The most interesting developments in PF toilet design

have been concerned with the squat-pan or pedestal seat unit. The Swedish company, Ifo

Sanitar AB, has developed an add-on unit for the Indian glass-fibre squat-pan which

converts it into a low-volume cistern-flush toilet. Only 1.5 litres of water are needed

per flush. The cistern can be any size (15-30 litres) as there is a special valve which

releases only 1.5 litres of water when the cistern is operated. This is especially useful

where municipal water supplies are intermittent and service is often only provided for 1-2

hours a day, as the cistern can hold enough water for 10-20 flushes. In Brazil, following

prototype development work by the Institute of Technological Research in São Paulo, three

major manufacturers are now producing low-volume flush toilets which can be initially

operated in the pour-hush mode, but which can be upgraded later to operate as low-volume

cistern-flush units. The Brazilian models are made in glazed ceramic-ware and, at US $5,

are becoming extremely popular in low-income urban slum communities. Duncan Mara, Department of Civil Engineering, University of Leeds, U. K. Technical

Advisor TAG (World Bank UNDP) Further information on TAG's activities in low-cost sanitation, and copies of the

various TAG Technical notes on VIP latrines and PF toilets can be obtained from Richard N

Middleton, Project Manager, UNDP INT/81/047, WUDOR, The World Bank, 1818 H St NW,

Washington DC 20433, USA.

|

|

DDOnline

Diarrhoea Dialogue Online Issue 18 August

1984  7 Page 8 7 Page 8

Sharing problems I am a nursing sister greatly involved in the care of aboriginal children in the

southern area of the Northern Territory of Australia. My work involves follow-ups;

guidance to people unfamiliar with the aboriginal ways; rural clinic every two weeks;

overall general paediatric care; teaching aboriginal health workers skills to better their

people in health ways. I feel it would be of great value for them to read your magazine Diarrhoea

Dialogue to let them know that other places have problems too, not just them.

Also I feel nursing staff would find it of great value. Would it be possible to obtain

regular copies for myself and staff? Sister Carmel Hattch, Paediatrics Clinical Assistant, Alice Springs Hospital and

Rural Area, Northern Territory, Australia.

Breastfeeding during diarrhoea I would like to congratulate you for packing so much information in such a concise and

lucid manner in Diarrhoea Dialogue issue 17 on

breastfeeding. The issue covers different practical aspects of breastfeeding like the

establishment and maintenance of lactation, the advantages to mother and infant, storage

of breastmilk etc. The pull-out poster was very inspiring. I am sure everyone who happens

to come across it will be stimulated to design and utilize similar material in their own

place of work. I would like to stress the importance of continuing breastfeeding during diarrhoea. For

one thing it will minimize weight loss due to diarrhoea, but, even more important, it will

reduce the number of mothers who switch to breastmilk substitutes after the infant has an

episode of diarrhoea. In South India an important reason for switching to breastmilk

substitutes and consequent lactation failure is the advice of misinformed health

professionals - doctors, nurses and health workers who advise withholding breastmilk for

2-3 days when the infant has diarrhoea. This often breaks the habit as well as the

mother's confidence in her own milk. More effort must be directed by all of us towards

protecting breastfeeding during diarrhoea. Dr Kingsley Jebakumar, Paediatrician, Church of South India Mission General

Hospital, Woriur, TiruchirapaIli-3, South India, 620003.

DD: health education My name is John A Chermack and I am a Peace Corps Volunteer from the United States

working in Honduras. I am a public health educator working in a town of 5,000 people. I

also will be working with surrounding pueblos of smaller sizes. I teach health, hygiene

and sanitation, nutrition and small vegetable gardening and a variety of health related

topics. David Werner in his book 'Helping health workers learn' suggests that your Diarrhoea

Dialogue newsletter is excellent. If it is possible I would appreciate being on your

mailing list and would also appreciate any other educational materials you might be able

to send. Any material in Spanish is of even greater value. John A Chermack, PVC, Marcala, La Paz, Honduras, Central America.

Editor's note: The Spanish edition of DD is available from PAHO, 525

Twenty-third Street, N.W., Washington D. C. 20037, USA.

Changing doctors' attitudes

The letters from Drs Puranik, Chandari and Nazmy in Diarrhoea Dialogue issue 16 as well as my experience in Trinidad and Tobago, Grenada, St

Vincent, St Kitts-Nevis and Venezuela have prompted this letter. I think all health

workers involved in managing children with diarrhoeal diseases would agree with me that

the major problem today, with the treatment of diarrhoeal disease, is the attitude of most

of the general practitioners. Invariably these doctors overprescribe antibiotics,

antidiarrhoeals, antimetics and antispasmedics for diarrhoea. Invariably an injection is

given. Invariably no information on rehydration or nutrition is given. We all know the

consequences, both to the children and to the doctors' lifestyles. Why has this not been

identified as the major problem? Are we scared of reasoning with our colleagues? Are they

not willing to talk over these things with us? What are the best ways to convince them,

not only of the benefits of ORT but of many other things, e. g. the misabuse of

antibiotics, that need to be corrected. Can we not identify the doctors in a country as

part of the problem of treating diarrhoea and give this the publicity it needs. Our

experience in Trinidad and Tobago suggests that this is a viable option when allied to the

more traditional means of reaching the medical practitioner e. g. seminars, letters from

the Hospital Consultant to the referring physician. Obviously however a great deal needs

to be done to answer these questions. David Bratt, Paediatrician, Port of Spain, General Hospital, Trinidad, W. I.

Editors' note: DD 16 reported on changing attitudes

among paediatricians in the U. K. towards ORT. Hopefully this may encourage a greater

acceptance of ORT amongst their colleagues in other countries.

Practical ideas Please send me six copies in addition to my own copy every month of Diarrhoea

Dialogue for distribution to my nurses and clinical officers in the Paediatric

diarrhoea ward of Kenyatta National Hospital. I find the publication very informative and

filled with practical suggestions and ideas on implementing oral rehydration therapy and

nutritional support in diarrhoeal illnesses. Your recent issue on breastfeeding was

excellent. Thank you. Dr Verna Jean Turkish, Lecturer in Paediatrics, Kenyatta National Hospital, P. O.

Box 30588, Nairobi, Kenya.

|

Scientific editors Dr Katherine Elliott and Dr William Cutting

Executive editor Denise Ayres

Editorial assistant Kathy Attawell

Editorial advisory group

Professor David Candy (UK)

Dr I Dogramaci (Turkey)

Professor Richard Feachem (UK)

Dr Michael Gracey (Australia)

Dr Norbert Hirschhorn (USA)

Professor Leonardo Mata (Costa Rica)

Dr Mujibur Rahaman (Bangladesh)

Dr Jon Rohde (USA)

Ms E O Sullesta (Philippines)

Professor Andrew Tomkins (UK)

Dr Paul Vesin (France)

Dr M K Were (Kenya) With support from AID (USA), UNICEF and WHO

|

Issue no. 18 August 1984

Page Navigation

This edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online is produced by Rehydration Project. Dialogue on Diarrhoea was published four times a year in English, Chinese, French, Portuguese, Spanish, Tamil,

English/Urdu and Vietnamese and reached more than a quarter of a million readers worldwide. The English edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea was produced and distributed by Healthlink Worldwide. Healthlink Worldwide is committed to strengthening primary health care and

community-based rehabilitation in the South by maximising the use and impact

of information, providing training and resources, and actively supporting

the capacity building of partner organisations. - ISSN 0950-0235 Reproducing articles

Healthlink Worldwide encourages the reproduction of

articles in this newsletter for non-profit making and educational uses. Please

clearly credit Healthlink Worldwide as the source and, if possible, send us a copy of any uses made of the material.

|

updated: 23 April, 2014

updated: 23 April, 2014

|