|

| |

Issue no. 22 - September 1985

pdf

version of this

Issue version of this

Issue

|

There is much information in this issue that is valuable

and useful. Online readers are reminded, however, that treatment guidelines and health

care practices change over time. If you are in doubt, please refer to

WHO's up-to-date Dehydration Treatment

Plans.

|

Pages 1-8 Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online Issue 22 -

September 1985

|

DDOnline

Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online Issue 22 September

1985  Page 1 2

Page 1 2

Newborns and diarrhoea

|

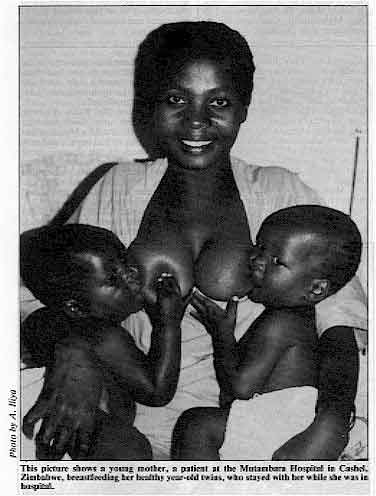

This picture shows a young mother, a patient at the Mutambara

Hospital in Cashel, Zimbabwe, breastfeeding her healthy year-old twins, who stayed with

her while she was in hospital. Severe diarrhoea can cause rapid death from dehydration in newborn infants if they are

given the wrong treatment. Our="#page4">centre pages describe the correct way

of giving oral rehydration therapy (ORT) for newborns with diarrhoea - in hospital, health

centre or home.

|

Doctors and nurses: a leading role

Enormous advances are being made in promoting the use of ORT at household and primary

health care levels. Unfortunately, places remain where this spread of knowledge still

fails to reduce the numbers of dehydrated children requiring hospital admission (see="#page7">page seven). Doctors and nurses everywhere should lead the way in

demonstrating the life-saving value of immediate ORT whenever diarrhoea occurs. With this

need in mind, this issue includes a 'clinical advice page' which covers management

problems related to oral rehydration therapy from a practical angle. There is also a

report of the way in which one hospital became more effective in treating children

admitted with diarrhoea. Breastmilk: natural protection The picture above, taken by Dr A. Iliya from Zimbabwe, wins our photographic

competition for the positive way in which it illustrates the benefits of breastfeeding -

essential for all infants and especially for newborns (see="su22.htm">insert

for other competition results). Breastmilk provides considerable natural protection

against diarrhoea. Both breastfeeding and the use of ORT need still wider promotion if the

lives and health of the world's children are to be properly safeguarded for the future. KME and WAMC

|

In this issue . . .

- Diarrhoea and the newborn

- Nurse training in Mozambique

- ORT - useful clinical advice

|

|

DDOnline

Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online Issue 22 September

1985  1 Page 2 3 1 Page 2 3

Nutrition forum

The International Nutrition Planners Forum held a conference in the U. K. in August on

'Nutrition and Diarrhoeal Disease Control'. More than 30 invited participants, including

two of DD's Editorial Advisors, took part. USAID and WHO were also represented and

discussions centered on ways to integrate the control of diarrhoea and the improvement of

nutrition. Policy and planning, implementation issues and research needs were considered

by separate working groups. The final report from the conference will include, in addition

to the findings of the working groups, special papers presented at the plenary sessions by

Dr Leonardo Mata, Dr Majid Molla, Dr Jose Mora and Dr Dilip Mahalanabis. Chairmen for the

conference were Dr Shanti Ghosh and Dr Demissie Habte. The main theme for="dd23.htm">DD23, 'Feeding and diarrhoea', had already been selected and

we hope that the conference report will be available in time for it to be summarized in

that issue. The value of this newsletter as a means of conveying information to health

workers at all levels was recognized by the invitation to the Dialogue to be

represented at this important and extremely valuable meeting. ORT in practice

In many areas the message about oral rehydration therapy and its effectiveness is

still not reaching those who most need to know. This story, from a DD reader in

India, and others like it which we hope to publish as a regular series in future issues,

illustrates that the message can never be emphasized too often. We invite other readers to

tell us about their personal experience of "ORT in practice". Mrs Subhadra Masalkar is a Community Health Guide (CHG) in the village of Jategaon

which is part of the Vadu Rural Health Project under the K.E.M. Hospital, Pune, India. Mrs

Masalkar is 31 years old, married and educated to primary school level. After being

recruited to become a CHG, she received three weeks training and has since attended two

more short refresher courses. She also has continuing training every month in various

skills relevant to her job. The use of oral rehydration therapy (ORT) is one of the skills

she has been taught. This story illustrates her personal experience in the use of ORT in

treating a diarrhoea case and how it changed the attitude of the villagers. Jategaon has a population of 1,000 people and has no medical facilities. Primary health

care is provided by the CHG. Early one morning, Mr Maruti Rao, aged 50 years, was suddenly

taken ill with diarrhoea and vomiting. Mrs Masalkar was called to the house. She

immediately started to give ORT using packets of ready prepared oral rehydration salts

(ORS). The ORS was dissolved in clean water and Mr Rao was asked to sip the solution

continuously. However, the villagers had no faith in such simple treatment and decided to

take Mr Rao to the nearest village, Shikrapur, three kilometres away, where a doctor would

be available. They hired a cart and throughout the journey the patient was given ORS

solution by Mrs Masalkar. When they reached Shrikrapur, they found the doctor was not

there and so decided to take Mr Rao on to the nearest town, a further kilometre away. On

the way, Mr Rao began to feel much better and his weakness and exhaustion had almost

disappeared. He himself decided that he did not need any injections or other medicines

from the doctor and the villagers began the journey home with him. Meanwhile, the packets

of ORS had run out so Mrs Masalkar, who had stayed with the patient all the time, decided

to start him on the equivalent home remedy, using a mixture of common salt and cane sugar

and water in the correct proportions as she had been taught. She prepared it right away

and the patient was soon completely recovered and rehydrated. The news of Mr Rao's dramatic recovery using only ORS solution spread like wildfire.

Mrs Masalkar has gained popularity and respect and now mothers knock at her door, even at

midnight. to ask for oral rehydration salts for treatment of diarrhoea in their children.

This proves that nothing can be more convincing than practical and simple demonstration. L. D. Puranik, K. E. M. Hospital Research Centre, Sardar Mudliar Road, Rasta

Peth,

Pune 411011, India.

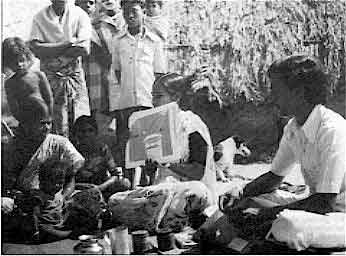

Health education about oral rehydration therapy in a village near

Pondicherry,

India.

This photograph was entered for our photographic competition by Dr R. D.

Bansal,

Professor of Social and Preventive Medicine, Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate

Medicine, Education and Research, Pondicherry 605006, India.

|

|

|

|

DDOnline

Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online Issue 22 September

1985  2 Page 3 4 2 Page 3 4

Reviews

Transitional diarrhoea in newborn infants. P. P. Maiya, M. Jadhar, M. J. Albert and

M. Mathan. Department of Child Health and The Wellcome Research Unit, Christian Medical

College Hospital, Vellore, India. Annals of Tropical Paediatrics, 1985, vol. 5, pp 11-14. Out of more than 3,000 full-term, breastfed infants not kept in the hospital nursery,

about two per cent developed acute watery diarrhoea between their third and sixth days of

life. Laboratory investigations showed that rotavirus and enteropathogenic serotypes of E.

coli could be found equally frequently in the stools of infants with diarrhoea and infants

without diarrhoea. Salmonella, shigella and cholera organisms were not found; other

possible pathogens, such as Cryptosporidia do not appear to have been looked for.

The diarrhoea was always brief (usually less than three days) and none of the babies had

signs of infection or dehydration. All received some extra fluid in addition to being

breastfed and all made a complete clinical recovery. It is suggested that such a

self-limited episode of diarrhoea soon after birth is not necessarily due to any type of

rotavirus infection. It could be caused by slow adaptation to breastmilk intake. The

microbial colonization of the gut that takes place after birth may also contribute to this

transitional diarrhoea. The syndrome obviously deserves further scientific investigation.

It is, however, clear that breastfeeding plays an important protective role in diarrhoea

among newborn infants and should always be encouraged. The following article may also be of interest to some readers: Enteropathogenic Eschericia coli (EPEC) and enterotoxigenic (ETEC) related

diarrhoeal disease in a neonatal unit. M. Adhikari, Y. Coovadia and J. Hewitt. Department

of Paediatrics and Child Health and Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine,

University of Natal, Durban, Republic of South Africa. Annals of Tropical Paediatrics,

1985, vol. 5, pp 19-22. Clinical immunity after neonatal rotavirus infection. Bishop R. F. et al, 1983 New

England Journal of Medicine 309 pp 72-76. Rotavirus infection in newborns does not prevent further rotavirus infection, but does

prevent serious diarrhoea. Usually, rotavirus infection causes acute watery diarrhoea in

children between six months and three years of age. Sometimes newborn infants in hospital

nurseries are infected with rotavirus but many, especially the full-term babies, do not

show signs of diarrhoea. In Melbourne, Australia, a group of young children who were known

to have been infected with rotavirus in the newborn period were compared with a group who

were not infected. On follow-up over the next three years, about half the children in both

groups developed rotavirus infections. Those who had been infected with rotavirus during

the newborn period had much less diarrhoeal illness and, if they did develop diarrhoea,

they were less ill.

Infection with rotavirus during the newborn period does not prevent reinfection

occurring later but it does protect against severe disease from the rotavirus

re-infection. Editor's note: Dr Ruth Bishop wrote a review for DD on rotavirus research (DD14, August 1983). Issue 16 (February

1984) included an article by Dr T. Flewett on expectations for a rotavirus vaccine.

Readers might also be interested to refer to: Interventions for the control of

diarrhoeal diseases among young children: rotavirus and cholera immunization. I de Zoysa

and R. G. Feachem, 1985, Bulletin of the World Health Organization: 63(3): 569-583. ORT in infants

Dr Menakshi Mehta and her colleagues of the L.T.M.G. Hospital, Sion, Bombay 400022,

have used oral rehydration therapy with babies of less than three months of age. ORS

solution (the WHO formula) was alternated with water, glucose water or breastmilk. None of

these children had periorbital oedema or other signs of overload of salt or water, even

though the possibility was anticipated and specifically looked for. (Personal

communication). Also see="#page4">pages 4 and 5. Nepal: preventing dehydration

|

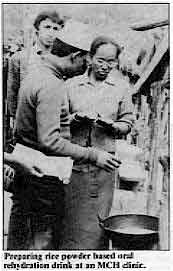

Preparing rice powder based oral rehydration drink at an MCH clinic.

Ruth Angove has written from Nepal to tell us about the successful use of an oral

rehydration drink made with rice powder, salt and water. Health workers and mothers were

shown how to mix and give the drink to both children and adults with diarrhoea. The rice

powder drink is very useful in the prevention of dehydration, the ingredients are readily

available locally and the easy recipe uses familiar ingredients and methods. Rice powder

or flour is a traditional weaning food in Nepal and the majority of both children and

adults who were given the rice powder oral rehydration drink greatly enjoyed the taste.

|

|

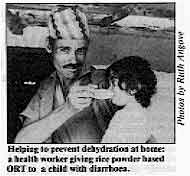

Helping to prevent dehydration at home: a health worker giving

rice powder based ORT to a child with diarrhoea. Further reading: Molla A M 1984 Advances with rice-powder ORS. Diarrhoea

Dialogue,="dd19.htm#page7">Issue 19, page 7. Molla A M et al 1982 Rice powder

electrolyte solution as oral therapy in diarrhoea due to Vibrio cholerae and Escherichia

coli. The Lancet, 12 June pp 1317-1319.

|

|

Ruth Angove, formerly Nutrition Advisor, United Mission to Nepal, PO Box 126,

Kathmandu, Nepal.

|

|

DDOnline

Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online Issue 22 September

1985  3 Page 4 5 3 Page 4 5

| Dealing with diarrhoea in newborn infants |

Approaches to rehydration

Daniel Pizarro reviews current knowledge about use of

oral rehydration therapy in neonates. Developing a standard approach to the rehydration of newborn infants who have diarrhoea

is not easy. Scientists still seek to establish an accurate picture of the neonatal fluid

and electrolyte metabolism and current concepts are constantly being updated by new

discoveries. Not only dehydrated but also healthy newborn infants may show a wide

variation in blood serum sodium levels. The kidneys of premature infants (those born too

early) have a poor capacity for sodium reabsorption during the first two weeks of life,

whereas full-term infants (born on or near the expected date) are able to reabsorb more

sodium than water during the same period. Although such observations might appear to

complicate the management of fluid and electrolyte disturbance in newborns with diarrhoea,

evidence from several clinical studies indicates that these infants can be treated safely

and effectively by means of oral rehydration therapy (ORT). Diarrhoea has very different causes in developed and developing countries. In the

former, diarrhoea in the newborn is unusual and may be due to inborn errors of metabolism

such as congenital enzyme deficiencies. It may also be associated with severe infections

like septicaemia or necrotizing enterocolitis, which require appropriate antibiotic

treatment in addition to rehydration. In developing countries, however, diarrhoea is a

relatively common problem among newborns, particularly if they are fed breastmilk

substitutes by bottle. The diarrhoea is almost universally infectious in origin and has

been reported in association with specific pathogens, for example, rotavirus,

enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) and cryptosporidium. Successful use of ORT Since the first report in 1976 of the successful use of ORT in neonates, many studies

have confirmed the effectiveness of this therapy. In addition, it has been found that

newborns with either hyponatraemic or hypernatraemic dehydration can be successfully

treated with the same rehydration schedule. Hypernatraemic dehydration refers to patients

with a high serum sodium, greater than 150 mmol/litre, and hyponatraemic dehydration to

patients with a low serum sodium of less than 130 mmol/litre. The standard WHO recommended

oral rehydration salts (ORS) solution containing 90 mmol/litre of sodium should be used.

Calculate the volume of ORS solution required for rehydration. In moderate to severe

dehydration, this is 70-100 ml per kg body weight. This amount should be given gradually

over a few hours, either by cup and spoon, or by bottle if the infant is already being

artificially fed. After this initial rehydration period, the diarrhoea may continue and

the rehydration must be maintained by giving the infant 10 ml per kg body weight of ORS

solution, alternating with an equivalent amount of plain water after each liquid stool

until the diarrhoea stops. Feeding should begin as soon as the initial rehydration period

is completed.

|

This three weeks old infant recovered in eight hours with ORS

after being 10 per cent dehydrated.

At the National Childrens' Hospital (NCH) in San Jose, Costa Rica, ORT with 90

mmol/litre sodium and glucose electrolyte solution is the routine therapy for dehydrated

neonates. More than 300 newborn patients - 95 per cent of all newborns given ORT - have

been successfully treated without complications. From this experience, it appears that

there is no need to consider 'special techniques' to rehydrate neonates, but care is

needed not to overload them with ORS solution.

|

|

Importance of breastfeeding Practical experience at the NCH over the past seven years has shown that newborn

infants with diarrhoea, who show little or no sign of dehydration, can be treated by

breastfeeding alone. Those with moderate or severe dehydration receive ORS solution alone

during the rehydration phase which lasts less than eight hours. Once the infant is

rehydrated, breastfeeding is continued, along with ORS solution given after each liquid

stool. In infants who are not breastfed, their usual formula, diluted 1:1 with water, is

given once rehydration is achieved, and ORS solution is given after every liquid stool

passed. An alternative is to give full strength formula and alternate giving ORS solution

and plain water after each liquid stool passed. Where possible breastfeeding should be

encouraged. This treatment approach has been successfully used for neonates with diarrhoea admitted

to the NCH. Five per cent or less have needed to be treated intravenously - severely

dehydrated infants with shock, intestinal obstruction or paralysis, or with persistent

vomiting. The Costa Rican experience has been successfully shared by other countries,

Venezuela (310 cases), Mexico (172 cases), Paraguay (23 cases), Argentina (10 cases) and

El Salvador (10 cases). In Paraguay and Egypt, as well as in Costa Rica, low birthweight

infants weighing as little as 1050 gm have been successfully treated using this regime and

giving the fluids by nasogastric tube. Dr Daniel Pizarro, Chief, Emergency Service, Hospital National de Ninos, San Jose,

Costa Rica.

*Neonates or newborns are infants from birth to 28 days after. Further reading: 1. Arrant Bs Jr, 1982. Fluid therapy in the neonate - concepts in transition.

Journal of Paediatrics 101 387:389.

2. Pizarro D et al, 1979. Oral rehydration of neonates with dehydrating diarrhoeas.

Lancet 2 1209: 210.

3. Pizarro D et al, 1980. Oral rehydration of infants with acute diarrhoeal

dehydration - a practical method. Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 83 241:245

4. Pizarro D et al, 1983. Treatment of 242 neonates with dehydrating diarrhoea with

an oral glucose-electrolyte solution. Journal of Paediatrics 102 153:156.

|

|

DDOnline

Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online Issue 22 September

1985  4 Page 5 6 4 Page 5 6

| Dealing with diarrhoea in newborn infants |

Careful management

Nisar A. Mir considers the special problems that can

arise when treating diarrhoea in newborn infants. It is essential to:

- recognise diarrhoea immediately

- prevent dehydration occurring or undertake early rehydration

- treat any other illness in the infant

- restore adequate food intake as soon as possible.

Rapid dehydration The physiological characteristics of the newborn baby or 'neonate' result in more rapid

dehydration during diarrhoea than occurs with older infants. The more premature the

infant, the greater the risk of severe dehydration. Reduced fluid intake may result if the

neonate is unable to take breastmilk from its mother due to poor sucking ability or

lethargy due to illness. The fluid loss from the body caused by diarrhoea and vomiting may

be increased by water loss through the skin due to fever and from the upper respiratory

tract by rapid breathing, especially in hot, dry climates. Local treatment

|

Bottle-fed full-term newborn needing rehydration in neonatal unit. Regional and cultural factors should be considered in the management of diarrhoeal

diseases in neonates. For example, in Benghazi, Libya, where heat-caused fluid loss in

newborns makes early rehydration essential when an infant also has diarrhoea, the

electrolyte content of the drinking water is higher than normal and extra care is needed

in preparing rehydration fluids. It has, therefore, been possible to treat mildly

dehydrated infants with diarrhoea with pre-measured glucose and bicarbonate fortified

drinking water, rather than resorting to ORS solution.

|

In Kashmir, however, the winter

temperatures are very low, and many parents do not like to give ORS solution because they

believe cold drinks will cause the common cold. Tea is recognized as hot and not

considered likely to cause a cold. Based on this traditional belief, health staff advise

mothers to feed infants who have diarrhoea with milkless 'Noon-chai' - the popular Tibetan

tea made with salt and bicarbonate of soda and fortified with glucose (see="dd21.htm#page3">DD21 page three). Suitable and modified home

drinks are now accepted as having a useful place in the early management of diarrhoea. Danger signs for the newborn

While most small infants with diarrhoea can be managed at home, either with locally

available remedies similar to those described above or ORS solution, some need to be

referred to a health facility for further treatment and investigation if they do not

improve. Signs to indicate that this is necessary include:

- bloody diarrhoea

- poor sucking or swallowing - often if the infant is very premature, ill or unconscious

- vomiting or shock

- severe diarrhoea with dehydration of more than 5 per cent of body weight.

Referral to a hospital is also indicated if the infant shows no sign of improvement

after treatment at home for 24 hours, or if the mother, for any number of reasons, is

having difficulties giving oral rehydration therapy. Drug therapy Antibiotics and other drugs do more harm than good in newborn infants and should never

be given. The only possible exception is where the cause of the diarrhoea has been clearly

identified as shigella, campylobacter or giardia. Early feeding The newborn infant should be breastfed as soon as possible after birth. Feeding both

during and after the diarrhoea is essential. Newborns have very limited nutritional

reserves to combat starvation and quickly become hypoglycaemic. After an episode of

diarrhoea, an infant needs extra food intake to rebuild reserves and prevent the cycle of

diarrhoea and malnutrition. Breastfeeding should always be encouraged. Bottle-feeding

carries a high risk of infection and good hygienic standards must be observed to prevent

recurrence of diarrhoea. In some cultures, inappropriate semi-solid and solid foods are

sometimes given to the very young infant with disastrous consequences. Management of diarrhoeal disease in the newborn requires accurate diagnosis and quick

responses from health personnel and mothers, with emphasis on preventing dehydration by

increasing fluid intake and on ensuring adequate calorie intake through suitable feeding.

Neonates with diarrhoea should be closely monitored to ascertain those who need early

referral to a hospital or other health facility. Dr Nisar A. Mir, Department Neonatology, Sher-I-Kashmir Institute of Medical

Sciences, P. B. 27, Srinagar 190011, India.

|

|

DDOnline

Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online Issue 22 September

1985  5 Page 6 7 5 Page 6 7

Successful ORT

Bert Hirschhorn and Ahmed Youssef

lists some important points for doctors, nurses and other health practitioners to remember

when giving oral rehydration therapy.

- A health worker must show the mother how to mix and give the oral rehydration

solution. This is equally important in the clinic and at home, to ensure understanding and

correct use.

- ORT does not stop diarrhoea; it stops and reverses the dangerous dehydration caused by

diarrhoea. In 50 per cent of children under the age of three, treated with ORT, diarrhoea

will continue for three to four days or sometimes even longer. This must be explained to

mothers. Once children have been properly rehydrated, they should be given about 400-500cc

of ORS each day, as well as being fed, to maintain rehydration until the diarrhoea stops.

The child with watery diarrhoea

- A child who has passed just three watery stools will have lost 150-300cc of fluid (water

containing essential body salts). This dehydration represents a loss of 1.5 - 3 per cent

of body weight in a child weighing 10 kg. Once 2 per cent of weight is lost, the body

reacts to conserve water and electrolytes (body salts). The recommended WHO/UNICEF formula

for ORS contains 90 mmol/litre of sodium and is the correct treatment for dehydration. If

packets of ORS are not available, an equivalent home-made sugar and salt solution should

be used. Plain water, or other drinks which contain little salt, are not recommended for

dehydrated children, except where salt and sugar are unobtainable. In such extreme

circumstances, any drink available should be used to treat a dehydrated child.

- The child will often pass a large watery stool just after ORT has been started. Mothers,

and even some health workers, may believe the ORT has increased the diarrhoea. This is not

true. What is happening is called the 'gastro-colic' reflex in which anything entering the

stomach causes the bowel to expel its contents. ORT does not increase diarrhoea except

when too much sugar is used.

The vomiting child

- If a child vomits, stop giving ORS for five to ten minutes. Then give ORS at the rate of

one teaspoonful (5cc) a minute. This may seem slow but provides 300 cc per hour and will

nearly always prevent further vomiting.

- The amount vomited is usually smaller than the quantity of ORS taken. If the child

vomits less than four times an hour, enough ORS is probably being retained. If vomiting

persists (more than four times per hour), use a nasogastric tube to give the ORS.

The thirsty child

- A thirsty child is a dehydrated child. Once rehydration is complete, children usually

refuse more ORS, unless hungry and not being offered food.

- A child with hypernatraemia (high blood serum sodium content) may drink a large amount

very quickly but seldom vomits in spite of this rapid intake. The child's thirst is a good

guide to successful ORT.

The child who refuses ORS This may be because:

- the child is no longer dehydrated and wants food or sleep.

- the child is still dehydrated but tired and needs to be patiently persuaded to drink

(see below).

- the child is irritable because of some other cause such as another infection. A

nasogastric tube may be the answer but first try to give ORS with a plastic dropper by

slipping this between the child's clenched teeth and cheek. The child will usually swallow

as a reflex rather than spit out the ORS.

The weak or drowsy child

- The child who is conscious but too weak to drink may need to be rehydrated by

nasogastric tube or by intravenous infusion if in shock. It is worth first trying the

plastic dropper technique (or a 5cc plastic syringe without the needle) to squirt the ORS

into the child's mouth.

The sleeping child

- Seriously dehydrated children sometimes sleep with their eyes partly open so that only

the whites show. Sleep during rehydration means one of two things. Either the child is not

recovering quickly enough and is becoming unconscious and needs to be woken up and given

more ORS; or rehydration is complete and the child is ready for normal sleep.

Abdominal distension A distended abdomen in children with diarrhoea is caused by:

- giving salt solution without potassium, either orally or intravenously

- giving anti-motility drugs

- giving cow's milk feeds to a child with lactose intolerance

- surgical problem - this is rare.

Newborns

- Most newborns can take spoon feedings. If not, a plastic dropper or plastic syringe

without the needle can be used to give ORS. Newborns are often seen to suck at the tip of

the dropper.

The child on a nasogastric tube Use this:

- at night in hospital when both mother and child need sleep.

- in persistent vomiting when the child is not in shock.

- in emergency - for example while setting up an IV in a shocked child or transporting the

child to hospital.

When using a nasogastric drip, mark the starting level of the fluid with a piece of

adhesive tape. Write the time on this and mark in the same way the correct level for each

following hour. This is to check the drip is working at the correct rate. The child in shock See above - the weak or drowsy child.

- Give ORS in addition to the IV if the child is conscious, and stop the IV as soon as the

child is drinking well.

Feeding the child with diarrhoea

- Breastfeeding should be continued throughout ORT.

- The child with diarrhoea needs extra feeding as soon as rehydration is complete. If

bottle fed, give smaller amounts of the normal feed more frequently. There is no advantage

to the old method of 'slow reintroduction' of milk and the mother may dilute the feeds for

far too long a time. Older children should be given their normal foods but fed more

frequently for a few weeks. Yoghurt, orange juice, bananas and coconut water are

recommended to bring up the potassium level. (Do not give coconut water during rehydration

as its potassium content is too high).

Dr N. Hirschhorn, JSI, 210 Lincoln Street, Boston, MA. 02111, USA.

|

|

DDOnline

Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online Issue 22 September

1985  6 Page 7 8 6 Page 7 8

| Country profile: Mozambique |

Training nurses

Alfredo Pisacane looks at how a training programme aimed

at improving nurses' understanding and use of oral rehydration therapy in hospital has

contributed to a decrease in mortality due to diarrhoea in one hospital in Southern

Mozambique. Whether people die at home or in hospital in developing countries depends on the

setting (urban or rural), the local culture and the availability and accessibility of

health services (1). In the city of Xai-Xai in Southern Mozambique, with 40,000

inhabitants, between 50 and 60 per cent of the total number of child deaths take place in

hospital (2). Diarrhoeal diseases remain the first cause of admission (excluding the

winter months when the prevalence of measles is high) and, up to 1981, diarrhoea caused 21

per cent of all child deaths and 20 to 25 per cent of children admitted with diarrhoea

died. Our team (one paediatrician and four nurses) tried to find out the reasons for these

disturbing figures. We decided to start six months of in-service training to improve our

collective knowledge of the problems of the paediatric ward and the needs of the patients.

Part of the training was related to diarrhoeal diseases. Towards a scientific approach The training consisted of daily 15 minute meetings of one doctor and one nurse and

weekly general meetings of one hour. In the short daily meetings, we observed the children

together checking the effects of dehydration on vital bodily functions such as pulse rate,

respiration rate, blood pressure, urine output and weight; and evaluated signs of

dehydration. At our general meetings, we tried to agree on the correct management of a

situation, and we wrote short notes about our discussions which now constitute a manual

for in-service training*. We also obtained slides of nurses carrying out a definite task,

for example, showing mothers the quantity of oral rehydration solution to give to their

children, checking the weight at the beginning of and four hours after starting

rehydration and checking urine output. In this way, we obtained after some weeks a more

scientific approach to diarrhoea treatment as is shown in the following sample from our

manual: What nurses must know:

- physical signs of dehydration

- vital signs affected by dehydration

- how frequently to check vital signs and weigh the child

- how to carry out oral and IV rehydration

- how to assess the improvement or the worsening of the condition of the child

What nurses must be able to do:

- check vital signs at admission and at least every four to six hours

- assess physical signs of dehydration at admission and after four to six hours

- check urine output if requested by the doctor

- give (and explain carefully to the mothers how to give) the right quantity of oral

rehydration solution over the right period of time

- start IV infusion when requested by the doctor

What nurses must be able to decide:

- when to call the doctor in relation to deterioration of physical signs of dehydration or

vital signs, or decrease in weight.

- if there is frequent vomiting, whether to continue with ORT or call the doctor to start

an IV infusion

The evaluation After six months, we decided to evaluate our training. The personnel were the same both

before and after the training; criteria for admission and for IV rehydration remained the

same; the age distribution of the patients and the incidence of diarrhoea did not change. Even if it is difficult to conclude that nurse training is the only factor for the

observed decrease in child mortality in hospital due to diarrhoea, it seems to play an

important role in our situation. In other countries like Mozambique, where the death rate for diarrhoeal diseases is

still high in spite of diffuse practice of ORT, improved training of nurses could be a

cheap and effective means of intervention.

|

Indicators of nurse performance

Nurses' recording of data for children with diarrhoea. First trimester 1981 and 1982.

|

|

1981 |

1982 |

| Admissions |

30 |

34 |

- pulse checked during first 24 hours

|

0 |

24 |

- weight checked after six hours of rehydration

|

0 |

24 |

- diuresis checked during first 24 hours

|

0 |

18 |

|

|

0 |

24 |

|

|

1 |

15 |

Indicators of health status. First trimester 1981 and 1982.

|

|

1981 |

1982 |

| Total admissions |

450 |

553 |

- admissions due to diarrhoea

|

30 (6.6%) |

34 (6.4%) |

- children treated with IV infusions

|

5 |

5 |

- children who died - all causes

|

35 |

17 |

- children who died from diarrhoea

|

9 |

1 |

- case fatality rate for diarrhoea

|

30% |

3% |

|

Dr Alfredo Pisacane, Instituto di Paediatria Universita di Napoli Via

Surgio Pansini 5, 0131 Naples, Italy * For further information about the manual, write to Dr Pisacane at the the

doctor address above. 1. Puffer RR and Serrano CV 1985. Pattern of mortality in childhood. Pan American

Health Organisation Scientific Publication No. 32.

2. Registry General, Xai-Xai, Mozambique 1981.

|

|

DDOnline

Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online Issue 22 September

1985  7 Page 8 7 Page 8

Convinced about ORS The participants in our first national training session in Management of Acute

Diarrhoea were all physicians involved in diarrhoea case management. The evaluation of the

training course showed that everybody shared the view that it was the practicals - the

administration of ORS, involving the mothers in spoon-feeding of children with mild to

moderate dehydration - that had convinced them of the acceptability and effectiveness of

ORS. Dr Mariam Claeson, WHO, P. O. BOX 3069, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Unnecessary prescribing I work in government service in Iran and I have read every issue of Diarrhoea

Dialogue. You present everything in an informative and creative way. I have found

whilst working in Iran that most of the doctors in private and government service

prescribe multiple antibiotics for simple diarrhoea. This type of attitude may be due to

lack of confidence or lack of recent information. Diarrhoea Dialogue solves both of

these problems by giving up-to-date scientific information and showing them how to treat

diarrhoeal disease confidently with ORT. The doctors would then not waste costly

antibiotics on their patients, and would save the patients money. In the long run they

would also prevent patients from becoming immune to antibiotics. If every doctor in the

developing world treated patients with diarrhoea properly, countries would save tons of

antibiotic syrups such as furoxone, ampicillin, chloramphenicol and neomycin . Here in my part of Iran, patients like a lot of medicine even for a little illness. If

a village mother brings her child with diarrhoea to the doctor, she expects him to

prescribe at least half a dozen drugs. She takes it for granted that antibiotics will cure

her child, and neglects the main part of the treatment - rehydration. In future, with the

enlightenment of the public with Diarrhoea Dialogue, attitudes may change. Dr N M Reddy, Khosf, Birjand, Korasan Province, Iran.

Local remedies CRS in Mauritania operates a monthly food and nutrition (F&N) programme serving

approximately 40,000 pre-school age children and 30,000 mothers country-wide. Health and

nutrition education is an integral part of the programme and diarrhoea management is

particularly important in this environment. The Mauritanians who work in the F&N

centres are trained to teach mothers about dehydration and ORT. They know the recipe for

the sugar/salt solution and are familiar with the UNICEF packets which are widely

distributed to health centres in Mauritania. Unfortunately Mauritanian women are often

reluctant to give water to a child suffering from diarrhoea, particularly during the cold

season, when water is completely withheld from a sick child. Most Mauritanian mothers do traditionally treat diarrhoea with a rice porridge often

containing seeds from the baobab fruit. This can be an effective treatment. They

additionally give their sick children a beverage of diluted sour milk (usually made from

powdered milk and soured with yoghurt) which is sweetened with sugar. Our question is as

follows. Can an effective ORT solution be made by simply adding a pinch of salt to the

sour milk beverage or by adding sugar and a pinch of salt to a diluted rice porridge?

Would it be safe and effective to add a UNICEF packet to either of the two? By promoting and strengthening already existing means of diarrhoea management we feel

we can achieve greater results. We look forward to your reply. Jill Gulliksen, Food and Nutrition Project Manager, Catholic Relief Service, B. P.

539, Nouakchott, Mauritania.

Editor's note: We asked Dr Mahalanabis of the Diarrhoeal Diseases Control

Programme at WHO to answer Jill Gulliksen's queries. "Can an effective ORT solution be made by simply adding a pinch of salt

to the sour milk beverage?"

As we understand it, the sour milk beverage refers to diluted yoghurt with added sugar.

Although we have not studied this, we believe that such a beverage with an appropriate

amount of added salt could be an effective ORT solution for early home therapy to prevent

dehydration. "Can an effective ORT solution be made by adding a pinch of salt to a diluted

rice porridge?"

Evidence so far suggests that rice powder suitably cooked and diluted (i.e. to contain

30 to 50 gm dry rice per litre), with added salt, may be useful for early home therapy to

prevent dehydration in infants and children older than three months. Sugar should not be

added to such a solution. The efficacy of such a solution in infants less than three

months old has not been determined. It should be noted that neither of the above solutions are suitable for treating

dehydration. For treatment, a more complete formulation such as the one recommended by

WHO/UNICEF should be used. "Would it be safe to add a UNICEF packet to either of the above

solutions?"

It is not advisable to add UNICEF packets to either diluted sour milk with or without

added sugar, or diluted rice porridge with or without added sugar. WHO/UNICEF packets

should be made up in water used for drinking. Adding such a packet to either of these

solutions will increase the carbohydrate concentration, which is undesirable, and in the

case of the diluted sour milk could also increase the sodium concentration.

DD for training I am a doctor from Bangladesh working with refugees in Somalia. We are involved in

primary health care and my responsibility is to train and supervise the medical staff

working in the refugee camps. Diarrhoea is the major killer. I received some issues of DD

from a friend of mine and I believe it will be very useful for me and my staff. Please

include my name on your mailing list for five copies of each issue. Dr Akran Hossain, P. O. Box 1502, Mogadishu, Somalia.

|

In the next issue . . .

DD 23 will focus on diarrhoea, growth and

nutrition

|

Scientific editors Dr Katherine Elliott and Dr William Cutting

Executive editor Denise Ayres

Editorial assistant Kathy Attawell

Editorial advisory group

Professor David Candy (UK)

Dr I Dogramaci (Turkey)

Professor Richard Feachem (UK)

Dr Michael Gracey (Australia)

Dr Norbert Hirschhorn (USA)

Professor Leonardo Mata (Costa Rica)

Dr Mujibur Rahaman (Bangladesh)

Dr Jon Rohde (USA)

Ms E O Sullesta (Philippines)

Professor Andrew Tomkins (UK)

Dr Paul Vesin (France)

Dr M K Were (Kenya) With support from AID (USA), UNICEF and WHO

|

Issue no. 22 September 1985

Page Navigation

This edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online is produced by Rehydration Project. Dialogue on Diarrhoea was published four times a year in English, Chinese, French, Portuguese, Spanish, Tamil,

English/Urdu and Vietnamese and reached more than a quarter of a million readers worldwide. The English edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea was produced and distributed by Healthlink Worldwide. Healthlink Worldwide is committed to strengthening primary health care and

community-based rehabilitation in the South by maximising the use and impact

of information, providing training and resources, and actively supporting

the capacity building of partner organisations. - ISSN 0950-0235 Reproducing articles

Healthlink Worldwide encourages the reproduction of

articles in this newsletter for non-profit making and educational uses. Please

clearly credit Healthlink Worldwide as the source and, if possible, send us a copy of any uses made of the material.

|

updated: 23 August, 2019

updated: 23 August, 2019

|