|

| |

Issue no. 32 - March 1988

pdf

version of this

Issue version of this

Issue

|

There is much information in this issue that is valuable

and useful. Online readers are reminded, however, that treatment guidelines and health

care practices change over time. If you are in doubt, please refer to

WHO's up-to-date Dehydration Treatment

Plans.

|

updated: 23 April, 2014

Pages 1-8 Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online Issue 32 - March

1988

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 32 March 1988  Page 1 2

Page 1 2

Weaning breastfeeding, and diarrhoea

The two most recent Dialogues have looked at the associated topics of women.

water, sanitation and family health in both rural and urban settings. It is clear that

most of the direct work burden within households is borne by women as they try to make

sure there is water, food and safe surroundings for their children. Most valuable gift - breastmilk Children are most at risk during infancy and early childhood before they develop their

own immunity to dangerous infections in the environment. To grow up healthy. they must be

fed adequately and safely: and they need to learn good health behaviour like use of

toilets, and handwashing afterwards and before eating. Mothers work hard in most societies

(see="dd30.htm">DD30). There is, however, nothing mothers can give to

their babies which is as valuable as their own breastmilk. It is not only the perfect food

for the first few months, but also provides protection against infectious diseases like

measles, pneumonia and diarrhoea (1,2) Weaning - time of extra danger

|

Breastfeeding

protects against the dangers of infection.

After the age of 4-6 months, babies need more than just

breastmilk. and weaning towards

the normal family diet must begin. Weaning makes extra work and is a time of extra danger

from infection and. malnutrition. 'Weanling diarrhoea' is a well recognized problem (see DD6.). Breastfeeding protects against these dangers. It should be

continued throughout weaning and always during oral rehydration therapy (ORT) for

diarrhoea (see="#page4">page 4).

|

|

The="su32.htm">insert in this issue gives information about how to wean

successfully and repeats some of the points made about domestic and environmental hygiene

in DDs="dd30.htm">30 and 31. KME and WAMC 1. Victoria C G et al. 1987 Evidence for protection by breastfeeding against

infant death from infectious diseases in Brazil. Lancet, 2 pp 319-323. 2. Briend A et al. 1988. Breastfeeding, nutritional state arid child survival

in rural Bangladesh. BMJ, Vol. 296, pp 879-881.

|

In this issue.. .

- Country reports from India, Jordan and Mozambique

- Weaning insert

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 32 March 1988  1 Page 2 3 1 Page 2 3

ORS: flavouring and colouring

WHO and UNICEF have consistently recommended the use of ORS compositions containing

only the four basic ingredients - sodium chloride, potassium chloride, glucose and sodium

bicarbonate or trisodium citrate, dihydrate - for an effective solution. However, many

commercially available products contain flavouring and some also a colouring agent.

Advantages

Theoretically, flavoured ORS may be more acceptable to children - they may drink it

more readily - and it may therefore increase ORS use. Although flavour or colour do not

increase or decrease ORS effectiveness in treating dehydration - its most important role -

improved taste may help to achieve more widespread popular use of ORS particularly in the

prevention of dehydration and in post-rehydration maintenance therapy.

Disadvantages

The theoretical disadvantage of flavouring or colouring of greatest concern is the risk

of over-consumption of ORS and consequent hypernatremia (too great an intake of sodium).

However, there is no documented evidence to support this theory. Giving too little OR

fluid is a much more common and serious error. Colouring of ORS has led to changes in

stool or urine colour causing confusion in diagnosis in some cases. Adding flavour or

colour also adds to the cost of ORS, but this may be more than offset by greater

acceptability and hence more widespread use.

CDD Update, November 1987, WHO/CDD, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland.

WHO is supporting a study to investigate this issue and would welcome data from

additional studies.

|

Cholera update

The seventh pandemic of cholera continues, but a simple approach is now available to

prevent deaths. Experience has shown that cholera is not a major public health problem in

a country or a community that has a properly organised programme for the control of

diarrhoeal disease.

- Cause

Cholera is an acute infection of the intestine caused by the bacterium called Vibrio

cholerae. The vibrio that is responsible for the current, seventh pandemic was named

after the El Tor Quarantine Camp (in Sinai) where it was first isolated. It is now called V.

cholerae, biotype eltor.

- Symptoms

The incubation period for cholera is short, between less than one day to five days. The

symptoms are profuse watery diarrhoea and vomiting, causing dehydration and acidosis, Most

infected persons show no symptoms or have mild diarrhoea. A few may develop severe disease

and die within a few hours from loss of water and electrolytes unless treated.

- Transmission

Cholera can spread very fast, mainly through water and food consumed by persons living in

overcrowded communities, where facilities for excreta disposal and drinking water supplies

are poor. Studies have shown that V. cholerae biotype eltor may survive in

water. In newly infected areas, adults are usually affected. In endemic situations,

cholera is mainly seen in children (after infancy) and young adults.

- Geographic spread

The seventh pandemic began in 1961, when V. cholerae, biotype eltor spread

from Celebes, Indonesia to other countries in East Asia, reaching Bangladesh in late 1963,

India in 1964, (in India, but not in Bangladesh, the eltor type almost completely replaced

the classical V. cholerae), and the Mediterranean in the late 1960s. In

1970, cholera invaded West Africa, which had been free from the disease. The disease

spread either along the coast or rivers through fishermen or traders, and to other areas

of the continent along land routes of travel. Funeral gatherings, with the ceremonial

washing of dead bodies and feasting, also played an important role in its spread.

Eventually the disease became endemic, particularly in coastal areas where temperature,

humidity, rainfall and population density favoured its persistence.

- Treatment and control

Oral rehydration therapy has now been found to cure all but the most severe cases, and

these can receive the oral solution by nasogastric tube if intravenous fluid is

unavailable. But problems in cholera control still exist:

- The disease often occurs in areas where treatment facilities are unavailable.

- Recognised clinical cases are usually few. Very mild cases and asymptomatic infections,

often unidentified, are more frequent and may play a very important role in spreading the

disease.

- Though sensitive procedures for the laboratory diagnosis of cholera cases have been

developed, rapid diagnosis of carriers is still difficult.

- The eltor biotype is more resistant to environmental factors than the classical type and

survives longer in the environment.

- Chemoprophylaxis and vaccine

The ineffectiveness of currently available parenteral cholera vaccine is now common

knowledge. This is for various reasons. Currently available vaccine efficacy is only

around 50-60 per cent, lasting for 3-6 months; most vaccine producers do not test for

potency and produce vaccines that do not have the required potency: vaccination does not

alter the severity of the disease and does not reduce the rate of asymptomatic infections,

thus it cannot prevent the introduction of cholera into a country or its spread; the

vaccine takes 8-10 days to induce immunity and in children in endemic areas needs to be

given in two doses at10-28 days' interval.

Resources would be better used to improve water supplies and sanitation and hygienic

practices. Only when these are at a certain level does faecal-oral transmission of V.

cholerae become unlikely.

Mass chemoprophylaxis has been used extensively in the past by some countries, a number of

which used sulfadoxine despite its known toxicity. The effectiveness of this strategy has

never been demonstrated, not surprisingly since it is impossible to treat everybody in an

affected community at a rapid enough pace to prevent re-infection from untreated persons.

Also the effect of such drugs only lasts a few days. Use of mass prophylaxis in several

countries may also have contributed to the emergence of drug resistance by cholera vibrios

to multiple drugs. Many health administrators nowadays correctly use anti-microbials that

are safer and easy to administer (e. g. doxycycline), reserving them for cases and, when

the attack rate is high, their immediate contacts. Doxycycline is less likely to produce

adverse reactions than chloramphenicol and can be given as a single dose treatment, unlike

tetracycline which must be given over a period of at least two days.

- Be prepared

Cholera in an unprepared community is generally associated with a high mortality

rate (50 per cent or more), usually because treatment facilities are lacking. Panic often

ensues and the sick, as well as their family members and friends, travel long distances to

seek treatment, which spreads the disease. In contrast, mortality rates can be reduced to

below 3 per cent in communities with a properly organised programme for diarrhoeal

diseases control, where health staff and village health workers are trained to treat acute

diarrhoeas (including cholera) and are provided with essential supplies, especially oral

rehydration salts (ORS). They should also be trained to keep case records, enabling them

to notice promptly any change in the pattern of disease (age group, number of cases,

severity, etc.) that might indicate the possibility of an epidemic, which would need to be

reported.

See also WHO/CDD/SER 80.4 REV 1 (1986) Guidelines for Cholera Control.

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 32 March 1988  2 Page 3 4 2 Page 3 4

Communication guide

The WHO Diarrhoeal Diseases Control (CDD) Programme has produced a guide for national

CDD programme managers with the aim of improving communication activities and assisting

countries in designing, planning, implementing and evaluating the communication component

of their CDD programme. It covers many important areas including, for example, the timing,

appropriateness and sustainability of communication activities. Communication: A Guide

for Managers of National Control of Diarrhoeal Diseases Programmes, produced in

collaboration with UNICEF, is now available in English. It will soon be available in

French and Spanish. From the CDD Programme, WHO, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland.

Puppets for Better Health -

A Manual for Community Workers and Teachers

by Gill Gordon, has recently been published by Macmillan.

There are chapters on how puppets can be used for health education in a community, how

to make up stories that are locally appropriate, making puppets and other items needed for

a show, preparing and putting on a puppet show. and how to follow up the messages used.

Available from: Macmillan Distribution Limited, Houndsmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire

RG21 2XS, UK. Price: £7.50 plus p and p.

|

Intestinal worms The latest issue of Health Technology Directions, Volume 7. Number 3. 1987,

focuses on intestinal worms: diagnosis and treatment; prevention; and programme issues.

Copies of Directions (a newsletter published three times a year), and a

bibliography on intestinal worms are available free of charge to health programme managers

in developing countries. from PATH, 4 Nickerson Street, Seattle, WA

98109-1699, USA. Eye health bulletin This is a new bulletin from the International Gentle for Eye Health, Institute of

Ophthalmology, London (WHO Collaborating Centre for the Prevention of Blindness) for all

concerned with community eye health. The first edition will include articles on world

blindness, malnutrition and the eye, surgical repair of the penetrating eye wound, and

working with mothers for change. Community Eye Health will be sent on request by

airmail (free of charge). For copies please write to: Dr Murray McGavin, Managing

Editor, 'Community Eye Health', 27-29 Cayton Street, London EC1V 9EJ, U.K. Hospital 'friends' Following the news item in issue 28. Dr Anne Savage has received over 80 letters

from DD readers in overseas rural hospitals requesting equipment and medical

supplies. Dr Savage is currently seeking support for these requests and has asked us to

inform DD readers who wrote to her that she will contact them as soon as possible. Poster competition

Over one thousand children worldwide have sent in entries for the DD poster

competition. They are all excellent and choosing the winners is going to be very

difficult! Posters will be judged in April by the Editors, UNICEF, Save the Children Fund

and others. The results and the winning entries will be featured in a special

insert in DD 33 DD 33 in June.

Change of address

AHRTAG will be moving to 1 London Bridge Street, London SE1 9SG. U. K. in April 1988. DD

readers are requested to send all future correspondence to this address. |

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 32 March 1988  3 Page 4 5 3 Page 4 5

India CDD market research

The findings of a sample survey of rural areas of India have radically changed the

strategy of the national diarrhoeal diseases control programme. As part of the CDD programme a nationwide survey was recently carried out to gain a

better understanding of beliefs and practices relating to diarrhoea. Included in the

survey were village mothers. paramedical workers, chemists (pharmacists) and doctors in a

representative sample of rural villages. Following this, a questionnaire was developed,

field tested and revised, and given to 5,400 mothers whose children under five had

recently suffered an episode of diarrhoea. The initial assumptions upon which the

programme design had been based have been largely reversed or substantially revised as a

result of the survey. Results

- More than two-thirds of mothers recognised death as a possible outcome of diarrhoea and

the great majority take diarrhoea quite seriously. However, there is a tendency to wait

for three to five days before the illness is thought to be severe.

- All lactating mothers continued to breastfeed their children in spite of contrary advice

from some medical professionals. In addition, 76 per cent of mothers gave extra water to

drink and 42 per cent gave other fluids. In some 2,000 children who had been weaned, 91

per cent of mothers gave extra water to drink, 60 per cent another household fluid and 51

per cent gave both. Mothers gave fluid in response to thirst and in the hope of offsetting

weakness which was the symptom most recognised as associated with diarrhoea.

- In contrast to popular belief and frequent medical advice, mothers did continue to give

food in 74 per cent of cases. A majority of mothers, however, changed the child's diet,

attributing the illness to dietary reasons. Some staple foods were dropped from the diet

and almost half were given less food to eat than usual. Feeding was not stopped because of

the widespread belief that diarrhoea causes weakness and that energy must be provided to

the child if it is to recover.

- Sixty-five per cent of mothers had consulted someone outside the home during the last

episode of diarrhoea in their child; most of these consulted a 'doctor', qualified or

otherwise, while only 7.5 per cent consulted a health centre or public health worker.

Treatment in the great majority of cases was with:

- tablets or capsules (70 per cent)

- syrups (54 per cent)

- intramuscular injections (40 per cent)

- ORS (6.2 per cent).

- Treatment costs averaged Rupees (Rs) 38 per episode (about $3) and fewer than 5 per cent

had paid less than 5 Rs. Respondents expressed the desire to pay for medical care which in

their view was better than that obtained free.

Home available fluids and ingredients All households had some available fluids that they would give a child with diarrhoea,

but most did not contain salt, and many, like water or tea, were lacking in ingredients to

promote absorption. Seventy-three per cent of households had refined sugar, or

gur,

available, 95 per cent had salt, and 83 per cent had rice. Only 8 per cent had neither

rice. sugar nor gur. Thus the ingredients for a home-made solution are almost universally

available, even in the poorest rural households. As rice water was a widely accepted drink for children with diarrhoea, questions were

asked about the frequency of cooking and lighting fires. Most respondents had fuel to make

a fire, mostly wood or dung. While preparation of acceptable home solutions is possible,

only 17 per cent were aware of sugar-salt solution, in spite of years of promotion through

health education messages. In some southern areas, there was a higher level of awareness

about sugar-salt solution (almost 50 per cent) but less than half of those questioned had

ever used these solutions due to confusion about the correct formula. ORS use and awareness

Nationwide. just over a third of all respondents had seen a packet of ORS and knew it

is used for diarrhoea. Seventy-two per cent of those who were aware of ORS had used it

(about a quarter of all respondents).

|

Surveys are a useful method of finding out whether mothers can

correctly prepare oral rehydration solution.

Most solutions were made in one glassful amounts, using a teaspoon or plastic scoop to

measure the ORS into a glass of water. Fewer than 10 per cent of users had ever mixed the

entire packet at a time, in spite of directions to use in one litre of water. Tests

of-proper mixing showed widespread over-dilution: a tendency to use 'less salts' and 'more

water' was almost universal. People expect ORS to stop loose motions, an expectation that

was widely viewed as fulfilled. Quenching thirst. prevention of weakness and cooling were

other expectations felt generally to be satisfied by ORS users.

|

|

Health workers Finally, questions were asked about accessibility of village based workers and their

knowledge of health matters. School teachers were known in three-quarters of the villages,

dais in half and volunteer village workers in a quarter to a third. Government paramedical

workers were known by only 15 per cent and in some areas of the country by fewer than 5

per cent. Credibility of all these was equally high, making teachers by far the best

potential route for communication of information about diarrhoea. Rethinking the strategy These results have led to a major rethinking of the national diarrhoeal disease control

strategy. Efforts will now be intensified to reach health professionals, particularly

those who call themselves 'doctors', through commercial drugs salesmen, chemists and

professional literature. Reorientation seminars, to be attended by all members of the

Indian Medical Association, in the modern use of ORS are already underway. The medical

professionals are being mobilised to carry the message, first to their colleagues and then

to the public to assure them that the use of an ORS packet is the correct procedure at

whatever level of health worker consulted. Public media are building upon the existing tendency to use appropriate fluids

available in the home rather than a specially prepared sugar-salt solution and to continue

feeding, to encourage and promote what mothers have already been doing; emphasising giving

more fluid, earlier, and more frequent feeding of the child. If public and professional

perceptions now reinforce the practice of continued fluids and feeding and the expectation

that curative services will provide ORS packets, then drinking will indeed become the norm

for the treatment of diarrhoea in India. The importance of this type, of pre-programme

market research to the design and implementation of national programmes in diarrhoea

management cannot be over-emphasised. This study was conducted by the Indian Market Research Bureau for the Government of

India, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, funded by UNICEF.

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 32 March 1988  4 Page 5 6 4 Page 5 6

| ORT in practice: Mozambique |

Evaluating effective use

Oral rehydration therapy has been promoted in Mozambique since treatment

guidelines were first drawn up in 1977. DD reports on a recent evaluation. Before revising Mozambique's diarrhoeal disease control strategy, studies were carried

out to evaluate: health centre management of diarrhoea; the practicability of advice given

to mothers; and effective use of ORT in the home. A simple study design was used. Medical students or paramedical workers observed the

case management of diarrhoea in the health centre using a standard checklist, and

interviewed the parent or guardian immediately after the consultation. Children were then

followed up in the home the next day and the parent interviewed again. Problems found In the health centres observed, 77 per cent of mothers were either given oral

rehydration salts (ORS) for their children or advised on home therapy with alternative

solutions. Thirty-six per cent were prescribed antibiotics but none antimotility drugs.

Despite the high prescription rate of ORS. instructions on its preparation and use were

brief, incomplete and rarely accompanied by demonstration or commencement of oral

rehydration in the health centre. All this was reflected in the follow-up findings.

Although 84 per cent of mothers who said they had given ORS could state how to prepare it,

only 42 per cent had prepared it correctly, mainly due to lack of litre bottles. The

quantity was in most cases insufficient. Of the 88 per cent of mothers who said they had

given ORS, 60 per cent had given less than half a litre during the previous 23 hours, and

many had only given one teaspoonful three times a day, similarly to the other medicines

prescribed. Although in the capital city 93 per cent of homes had a litre bottle and all had salt

and sugar, in other areas availability of litre bottles varied from 7 per cent to 47 per

cent and of salt and sugar from 0 to 60 per cent of homes. Traditional remedies included

cereal-based solutions and ground leaves or roots boiled in water, but they were given in

small quantities, as medicines rather than as a means of liquid replacement. Revising the strategy The studies showed many positive points - health workers did prescribe ORS and not

anti-motility drugs; mothers knew how to make up ORS and continued breastfeeding and

giving the normal diet to the child. However, OR solution was often given in insufficient

quantities: the challenge for the CDD programme is to ensure its effective use. To help achieve this, diarrhoea treatment norms have been revised and made more

flexible. The previous emphasis on salt and sugar solution as the alternative to ORS has

been changed to take into account the widespread shortages of these substances. New health

education messages and materials emphasise the importance of giving a sufficient quantity

of liquid as well as the correct preparation of ORS. Home solutions are recommended for

early treatment, the type of solution varying in different parts of the country. The results have also prompted a review of health worker training and supervision,

incorporating the need for health workers to find out from families what home-based ORS is

feasible and to demonstrate the preparation of ORS using locally available utensils. We believe that this simple method of evaluation may be useful for other programmes,

both to identify problems in case management, especially health education, and to evaluate

improvements after appropriately designed training has been carried out. Ministry of Health and Eduardo Mondlane Faculty of Medicine, Maputo Mozambique. Readers who would like a copy of the protocol used for this evaluation study

should write to Dr F T Cutts. SCF CP 1882. Maputo, Mozambique. A similar protocol

for use in evaluating diarrhoea case management in health facilities is available from the

CDD programme, WHO, Geneva.

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 32 March 1988  5 Page 6 7 5 Page 6 7

Jordan: diarrhoea and the urban poor

Even in modern cities of the Middle East such as Amman and Damascus where infant

mortality is relatively low, diarrhoeal disease is still a part of life for children in

low-income households. Leila Bisharat reports. Two surveys carried out in 1980 and 1985 among low-income squatter communities in

Amman, showed that while infant mortality was close to the national average, some children

in these settlements were twice as likely to die during the first three years of life as

others. The most important factors affecting child survival were the educational status of

the mother and the child's environment, including the type of water source used by the

family. quality of housing and so on. Diarrhoea incidence Both surveys took place in the winter when diarrhoeal episodes are more commonly

associated with viruses. especially rotavirus. In the 1980 survey, 17 per cent of infants

and children under three had had acute diarrhoea during the two weeks before the

interview.

|

Child

being weighed.

In 1985, following upgrading interventions (water, improved sewers, building

footpaths), the figure was 11 per cent*. The children were also weighed, and stool samples

taken to investigate the level of infection with intestinal parasites. Giardia infection rates were found to be high for all children over six months of age.

In 1980, giardia was observed in the stools of 36 per cent of all children under the age

of three and in 42 per cent of those aged 30 to 35 months.

|

(A recent survey in a squatter area of Damascus has shown similar giardia infection

rates (35 per cent in under threes). Only 3 per cent of households in the Damascus

squatter area are connected to the public water system). In Amman, in 1985, five years

after infrastructural improvements, testing among new groups of under threes living in the

same households as the previous groups found that only 17 per cent, showed evidence of

giardia in their stools. These findings encouraged policy makers to take action to improve

water supply and sewerage systems. Stool sample results can be used to draw political

attention to the link between contaminated living conditions and health, and encourage

quick action for physical improvements. Handwashing The importance of handwashing after defaecation to prevent the spread of diarrhoeal

diseases is well recognised. In 1980, despite a level of household incomes which meant

that almost all families could easily afford to buy soap, only 17 per cent of households

surveyed were seen to have soap available for handwashing near the toilet. Availability of

water was an important, but not exclusive factor - 26 per cent of households with a

watermains connection had soap as compared to only seven per cent of houses without mains

water supply. When all houses had been connected to mains water, 60 per cent of the

households had soap. Although hygienic practices had changed for the better, the second

survey showed that 40 per cent of households still did not have soap available for

handwashing near the toilet even when they had a functioning water tap inside each

latrine. Further improvements such as increasing access to clean water need to be

accompanied by health education in order to maximise health benefits. Sex differences in care during diarrhoea In addition to maternal education and surrounding environment, whether a child is male

or female can determine survival rates. Within the same household, child care practices

during diarrhoea vary according to the sex of the child. Among those children under three

who had had severe diarrhoea during the two weeks preceding the survey, males were more

likely to be taken to a doctor than females (44 per cent of the males and 34 per cent of

the females). Male children were also brought to the diarrhoea treatment centre at the

nearest major hospital more often than female children, and female children were

significantly more ill when they were brought for treatment. Thirty-three per cent of the

females had to be hospitalised while only 26 per cent of the males were; of those

hospitalised. 55 per cent of female children were severely malnourished compared to only

26 per cent of the males. Dr Leila Bisharat, PhD, Regional Adviser, Urban Development, UNICEF, Middle East and

North Africa. *Editors' note: The change from 17 per cent before the intervention to 11 per

cent after the intervention does not necessarily mean that the intervention had an impact.

To substantiate an impact, the investigators need to show first that 11 per cent is

significantly lower than 17 per cent, and, second that the two surveys were conducted

using identical methods, on the same population, and at the same time of year to allow for

seasonal fluctuations.

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 32 March 1988  6 Page 7 8 6 Page 7 8

Mother- child interaction and stimulation I have become increasingly aware that mothers interact differently with their babies

when they have diarrhoea and malnutrition to when they have other conditions such as

pneumonia or fractures. Despite the lack of proper toys, most mothers on the ward play with their children,

with the exception of those mothers whose children are admitted with diarrhoea and

malnutrition. These tend to sit quietly, or talk with other mothers leaving the child to

sit in the cot or bed. I am sure that the listnessness and lack of response due to

diarrhoeal illness and malnutrition can lead to a change in the normal interaction between

mother and child. Children admitted to hospital with diarrhoea have often stopped growing well. Most

hospitals and clinics try to teach mothers about nutrition and hygiene, as well as

providing a high energy diet. Some children, particularly those who are undernourished may

also lack sufficient stimulation for mental development. Reasons for this are many. In

poor families. mothers usually work for many hours a day and consequently have little time

to play with their children or may be physically separated from them. The malnourished or

dehydrated child can be apathetic and quiet and does not demand or get attention from the

mother or the rest of the family. Some will be miserable and cry often; they may be

difficult to look after and feed, and may anger or exasperate their mothers. Health workers or nurses can talk to mothers about ways in which they could stimulate

their child: by far the most important form of stimulation is talking to the baby, even

when it is sick. Give mothers practical suggestions that use resources they already have.

Stimulate the sense of hearing by talking, singing, the radio, musical instruments,

shaking jars or gourds filled with beans, and pots beaten with sticks. Stimulate the

senses of smell and taste with fruit, flowers, vegetables and cooking smells. African

mothers commonly massage their children with Vaseline or oils. This is also important

stimulation. Improving the hospital ward Let the baby feel objects with different textures such as cloth, paper, plastic, wood

and metal. Bright colours, shiny objects, patterns and pictures, especially faces, all

stimulate the sense of sight. As babies become more mobile they need to spend more time

free to explore. They should not spend all day restrained, for example, on their mother's

back.

|

Toys can be made from simple everyday objects Show mothers on the ward by example. Make it bright and interesting. Make toys for the

ward from simple everyday objects. Make pictures or paint on the walls. Involve all the

staff - making pictures for children is fun and raises morale.

|

Wendy Holmes, Chinhoyi Hospital, PO Box 17, Chinhoyi, Zimbabwe. DD for schools I am a teacher at one of the primary schools in Bo, Sierra Leone and head of the School

Health Education Committee. I am teaching about personal and environmental hygiene and

they have started to keep their surroundings cleaner than before. I would like to request

regular copies of Dialogue on Diarrhoea issues to help me spread the

knowledge as a teacher. Dominic Gortor- Musa, 100 Dambara Road, Bo, Sierra Leone, West Africa. The right soaking solution

|

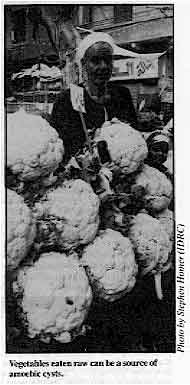

Vegetables eaten raw can be a source of amoebic cysts.

DD issue 27 about amoebiasis mentioned soaking vegetables

to be eaten raw in vinegar or dilute hypochlorite solution for 30 minutes. Here we use

potassium permanganate in our community kitchen. How effective is this? How long should

the raw salads be soaked? I would be very happy if you could give me precise information

on this point. We do use oral rehydration therapy here and are convinced of its value. We teach

mothers to prepare a home-made solution, as ready-made packets are quite expensive for our

patients and also most of the brands have up to 40g of glucose per litre!

|

|

Dr Anne Morejee, Meher Health Centre, Meher Free Dispensary, Avatar Meher Baba

Perpetual Charitable Trust, Meherabad, Ahmednagar, Maharashtra, India. Dr Sandy Cairncross, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine replies: Unfortunately,

potassium permanganate is of little or no use at all. The best measures to use are those

recommended in DD27 - soaking for 30 minutes in dilute

hypochlorite solution or vinegar followed by rinsing in boiled water.

|

|

DDOnline Dialogue

on Diarrhoea Online Issue 32 March 1988  7 Page 8 7 Page 8

ORT and vomiting

I am a registered nurse working with one of the general hospitals in Sokoto State,

Nigeria, where we have had a great deal of success with ORT. One question I have is this:

if the fluid is given to the child and the child vomits, is it right to give anti-emetics

like largactil (chlorpromazine) and, when the vomiting stops, should the administration of

ORT follow up? M A D Tambawal, General Nurse, General Hospital, Koko, Sokoto State, Nigeria. Dr N Pierce, CDD/WHO Research Coordinator replies: Oral rehydration therapy (ORT) can be considered as both curative and preventive with

regard to dehydration due to diarrhoea. When given to a dehydrated patient, usually in the

form of ORS (Oral Rehydration Salts), its purpose is to correct (cure) the dehydration by

restoring normal amounts of water and salts to the body. However, when given soon after

the onset of diarrhoea, before dehydration develops, usually as a home-made solution, its

purpose is to prevent the reoccurrence of dehydration. Vomiting happens frequently during diarrhoea, especially when the illness is caused by

rotavirus or cholera. Vomiting can occur, or continue, during the first hour or two of

ORT, after which it will usually diminish or stop. When vomiting occurs during ORT, fluid

administration should be continued after waiting 10 minutes but given more slowly in sips

at short intervals. Although it may appear that a large amount of rehydration fluid has

been vomited, most of what is given is actually retained, benefiting the patient.

Antiemetics, such as chlorpromazine should not be given because (i) they have undesirable

side effects, such as drowsiness, which can interfere with the continuation of ORT, and

(ii) the vomiting will usually subside as ORT is continued. Promoting ORT at the university level While Oral Rehydration Therapy has been proven to be effective in combating dehydrating

diarrhoea, in some areas it is not routinely applied. We have now treated more than 10,000

cases of gastroenteritis at our ORT centre at Mama Yemo Hospital in Kinshasa, Zaire and

the results have been excellent. There is now a vast body of information on the

usefulness, simplicity and life saving benefits of ORT. There is also new and important

physiological and pharmacological data in favour of using ORT as a primary and often

exclusive mode of treatment for diarrhoeal disease. In order to reach colleagues at the university and paediatricians at large, discussions

and conferences were organised at our monthly meetings of the Zairian Society of

Paediatrics, in which the encouraging results of ORT from our centre were presented.

Research data was presented at the Zairian National Paediatric Congress. Regular

scientific presentations, on physiology, and the newer concepts of the mechanism of

gastroenteritis, have led to a dramatic change in the attitude of practitioners. We believe that well-planned scientific conferences at the universities and

metropolitan hospitals, coupled with documentation of positive results from well-organised

ORT centres, will have a great impact on health professionals, enabling them to recognise

the value of ORT as the therapy of choice over the traditional methods of IV and

antibiotics. Once the faculty is convinced of the superior efficacy of this therapy, a

change in curriculum will be forthcoming. Dr F Davacbi, Professor and Chairman, Department of

Paediatrics, Mama Yemo Hospital,

Kinshasa, Zaire. Wrong idea about ORS ORT has given excellent results, preventing dehydration, electrolyte imbalance and

mortality from diarrhoea in a large number of Pakistani children suffering from diarrhoea.

I want to ask a question about the use of ORT. Please can you tell me if it is safe to use

ORS in newborns? Dr S M Inkisar Ali, Assistant Professor of Paediatrics, Dow Medical College,

Karachi, Pakistan. Editors' note: Data from Dr Daniel Pisarro in Costa Rica on the use of ORS in

more than 200 neonates has shown that it is safe. (Pisarro D. 1983. J. Paed. Vol 102. pp

153-6.) See also DD issue 22. Points about diarrhoea management Regarding chronic diarrhoea, I am convinced that the number of cases falls when

antibiotics are not given routinely. This is logical since the gut flora is allowed to

recover. In the 10 per cent of children in whom diarrhoea persists, a diet such as

porridge made from the local starchy staple or mashed bananas, containing 'bound water' is

often beneficial. This also helps to replace the lost elements K+ (potassium) and

Mg++(magnesium). In Uganda the custom of cooking beans in the ash from burnt leaves would

replenish K+ and Mg++' - are there any studies on the effectiveness of this practice? P E Harland, Professor of Child Health, University of the West Indies, Faculty of

Medical Sciences, St Augustine, Mt. Hope Medical Sciences Complex, Uriah Butler Highway,

Champs Fleurs, Trinidad, W. I. Editors' note: We know of no study which has specifically examined this

question. There are different factors which contribute to chronic diarrhoea. Pathogenic

bacteria is probably not common. Nor is sensitivity to the gluten protein of wheat.

Under-nutrition is more common in many communities. Therefore Professor Harland's

suggestions - avoiding antibiotics and using local foods - are appropriate.

|

Scientific editors Dr Katherine Elliott and Dr William Cutting

Managing editor Kathy Attawell

Editorial advisory group

Professor J Assi Adou (Ivory Coast)

Professor A G Billoo (Pakistan)

Professor David Candy (UK)

Professor Richard Feachem (UK)

Dr Shanti Ghosh (India)

Dr Michael Gracey (Australia)

Dr Norbert Hirschhorn (USA)

Dr Claudio Lanata (Peru)

Professor Leonardo Mata (Costa Rica)

Dr Jon Rohde (USA)

Dr Mike Rowland (UK)

Ms E O Sullesta (Philippines)

Professor Andrew Tomkins (UK)

Dr Paul Vesin (France)

Dr M K Were (Kenya) With support from AID (USA), ODA (UK), UNICEF, WHO Publishing partners

BRAC (Bangladesh)

CMAI (India)

CMU (China)

Grupo CID (USA)

HLMC (Nepal)

lmajics (Pakistan)

ORANA (Senegal)

RUHSA (India)

Consultants at University Eduardo Mondlane (Mozambique)

|

Issue no. 32 March 1988

Page Navigation

This edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea Online is produced by Rehydration Project. Dialogue on Diarrhoea was published four times a year in English, Chinese, French, Portuguese, Spanish, Tamil,

English/Urdu and Vietnamese and reached more than a quarter of a million readers worldwide. The English edition of Dialogue on Diarrhoea was produced and distributed by Healthlink Worldwide. Healthlink Worldwide is committed to strengthening primary health care and

community-based rehabilitation in the South by maximising the use and impact

of information, providing training and resources, and actively supporting

the capacity building of partner organisations. - ISSN 0950-0235 Reproducing articles

Healthlink Worldwide encourages the reproduction of

articles in this newsletter for non-profit making and educational uses. Please

clearly credit Healthlink Worldwide as the source and, if possible, send us a copy of any uses made of the material.

|

updated: 23 April, 2014

updated: 23 April, 2014

|